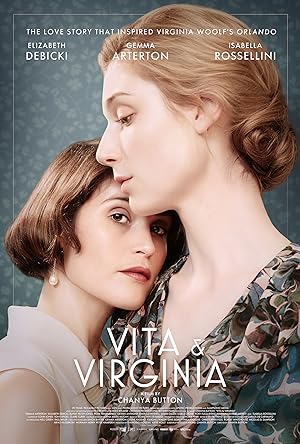

“Vita & Virginia” (2018) is a film adaptation of an Eileen Atkins 1992 play with the same title. The play and the film features correspondence between authors and lovers Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf. The biographical drama starts before the two have met. Popular and scandalous Vita (Gemma Arterton) admires Virginia (Widows’ Elizabeth Debicki) as a genius and is eager to meet her despite rumors of her madness. Initially distant, Virginia eventually reciprocates Vita’s interest and exchanges roles with her by becoming more ardent in her attentions. The film ends soon after the publication of Woolf’s “Orlando: A Biography,” which Sackville-West inspired and skyrocketed Woolf’s fame.

I wanted to see “Vita & Virginia” because I enjoy films about writers. My interest was renewed soon after seeing “Tár,” which references “Challenge,” a Sackville-West book written before the historical events featured in this film. Also Chanya Button directed it as her sophomore feature, and I am always interested in prioritizing women directors’ work. I did not get to see this film in the theaters because it barely lasted a week if it even made it to a theater near you. It received poor reviews, but regardless of quality, women led films generally get less theater space than their male counterparts. There was also some controversy because of the casting and historical accuracy. Woolf was older and shorter than Debicki. Outside critical circles, the film seems to be a popular sapphic film.

“Vita & Virginia” is a sumptuous, early twentieth century period film in terms of costume design, sets, production values and casting. In a vacuum, Virginia’s fur collared iconic appearance may seem glamorous, but compared to Vita’s elegant contemporary style, Virginia seems rustic. Vita’s aristocratic lineage and upper-class status is conveyed wordlessly in every scene. Without being familiar with their work, these visual signifiers contrast the writers’ personalities. Vita is period perfect whereas Virginia is represented as more timeless. In contrast, some of the soundtrack feels modern to reflect the characters place in society as subversive for their period though their appearance may seem quaint and conservative compared to our dress today. The film does an excellent job of plunging us into the middle of the characters’ lives and keeping us apprised without confusion. The movie does not have to orient us in terms of understanding the mores of the period and the parties’ place in society though it does use Vita’s disapproving mother, Lady Sackville (Isabella Rossellini), as the personification of prevailing standards. I am unfamiliar with either writer’s personal history, but was able to keep up with the considerable prose dumps.

“Vita & Virginia” focuses on the theme of romance as “not knowing someone altogether.” The movie is a dance between the two women wanting to know each other, but they differ in terms of what type of knowing satiates them. The first half of the film is told from Vita’s point of view then Virginia dominates the second. Because Vita is depicted as not as complex as Virginia, she is satisfied with proximity and getting Virginia to reciprocate her sexual advances. Virginia’s gifts attract Vita before Vita sees her. For Virginia, her attraction taps into reservoirs of imagination to fill in the parts that she cannot reach using her impression that Vita’s spirit has left on her. Virginia pulls a reverse Pygamalion with Vita, which is quite a feat considering Vita is a vivid individual to project upon. The room for coloring lies in Vita’s superficialness. Like Vita, Virginia is fascinated with the qualities in Vita that Virginia lacks: confidence, family history and wealth. Each woman is attracted to the other for what she does not possess, but Vita cannot stand the intensity for long and rushes back to shallower waters.

I am not into romance, but I found it tolerable in “Vita & Virginia.” When a titular character reads her letter, she faces the camera, i.e. the audience acts as a surrogate for the letter’s recipient. The background is blurred with the actor’s face filling the screen. The viewer gets inserted into their drama. Also because it is an attraction of minds first, I did not get bored. The film lacks a steady rhythm between scenes unfolding in characters’ lives and letter reading. Viewers will need to pay close attention to the dialogue to determine how much time has passed between scenes because there are quite a few time jumps otherwise a viewer may mischaracterize the characters’ reactions as melodramatic.

To heighten the tension, a husband may caution his wife, but that aspect of the story was not well explained in Vita’s case. They have an open marriage so is the hand-wringing fictional? In Virginia’s case, Leonard (Peter Ferdinando) had relatable concern because he is protective and accepted her as she was. While he rejects jealousy, the seeds are sympathetic because as depicted in the film, he thought that he was married to an asexual woman then must reconcile that her sexual side is unavailable to him. Leonard is the aspirational ideal significant other in a film filled with options because he respects Virginia’s mind and prioritizes her work. A brief Google search reveals that Virginia was not as averse to sex in real life and was pansexual.

Because “Vita & Virginia” involves writing, the film does get dialogue heavy and drags a bit in the middle when shifting from Vita to Virginia’s perspective. It is hard to depict writing because it is solitary quiet work. If you had endless scenes watching someone alone in a room with paper and pen or a typewriter, people would demand a refund. We get into the logistics of Virginia’s process, but not Vita’s—when does Vita find the time while traveling, partying, socializing, and collecting lovers? Instead the film has to find dynamic ways to communicate the creativity onscreen. The opening scene focuses on a printing press. The main signifier for writing is animated conversations about writing and sex by showing artists together, mostly The Bloomsbury Group.

Onto a random unimportant detail from “Vita & Virginia.” Was Dorothy Wellesley (“Misfits” Karla Crome), i.e. the Duchess of Wellington, black? I do not even know who she is, and Google was not that helpful. Also there was one black guy who worked at the Woolf’s printing press, and he gets one scene. I have no idea if this film was just complying with BFI Diversity Standards. While I do not want a film to explain why a black character is present, it felt kind of tagged on instead of organic. My view of diversity has changed over the years. If a film can only stand to have one minority of each gender, I get suspicious unless they are three dimensional characters with rich lives outside of the main characters. It is not radical to only have one black friend each. At least they were not paired up because they have so much in common, code for skin color.

I read a review about “Vita & Virginia,” which criticizes the film’s attempts at depicting Virginia’s mental state and frames it as magical realism. I disagree that the film was using magical realism, which I define as the real world having magical elements whereas the film was suggesting the opposite. Virginia hallucinates by imagining vines and flowers bursting in quotidian places and can be associated with her visits to a greenhouse. I associated it as a symbol of her burgeoning love. At one point, nature seems to attack her, but no one else sees it. I agree that depicting these hallucinations did not work, and while I do not know much about Woolf, at most she suffered auditory, not visual, hallucinations so the movie failed. In addition, it short changed Vita who confesses, “Do you ever feel that you record things rather than feel them?” Only towards the end of the film do we see Vita feeling vulnerable and considering her shortcomings, but I would found it tantalizing for the film to reconsider her actual difference without a diagnosis instead of framing them as flaws.

The production values of “Vita & Virginia” elevate it above a television movie. While Arterton may have pitched the movie to Button and had more glamorous screen time, Vita’s depiction feels less textured than Virginia’s. It felt as if the film dismissed her as a serious thinker, i.e. more of an influencer than a woman of substance.