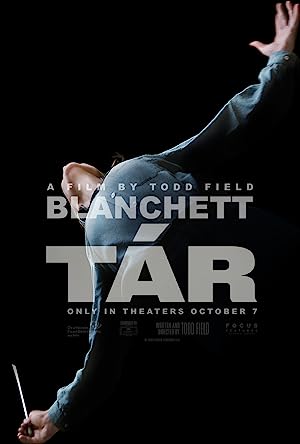

“Tár” (2022) stars Cate Blanchett as Lydia Tár, a genius conductor who is preparing for the Berlin Philharmonic’s live recording of Mahler’s 5th Symphony, which the pandemic interrupted, but what else can get in the way?

I saw a preview for “Tár” and knew that I wanted to see it in theaters. Blanchett is a great actor, and the preview was mysterious and evocative. It only irritated me that they marketed as a biopic of an actual person though the protagonist is fictional. I had no idea what I was walking into, and it felt like the right approach to the film, which sounds challenging at 2 hours 38 minutes long. When it ended, I was not ready to stop learning about the titular character. I would suggest watching the film then coming back and reading further.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Tár is a manipulative sexual harasser who wants to be the biggest person in the room. By preying on young talent that could become a future rival to her, she echoes her hero Mahler and eliminates potential competition. It starts as early as suggesting that her fellowship program should no longer be gender based to cover her tracks that she has been using it as a feeding ground. Later she finds ways to get her desired results by making others feel as if her ideas came from them. Throughout the film, she preaches against identity politics and accountability and privileges work over character. She protects the greats because she identifies with them and wants to claim their privileges. She overplays her hand, and the film chronicles her downfall, which is not an immediate, obvious possible outcome until the denouement.

The majority of “Tár” felt like Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-tale Heart” as if her latest victim haunted her before death. It feels like a ghost story and certain oneiric sequences evoke scenes from “Midsommar” (2019). Field also uses sound from “The Bair Witch Project” (1999). Her guilty conscience haunts her and cancel culture becomes a much-needed expulsion of her fears, which were unraveling her to the point that she was stealing her wife’s prescription medication. After her downfall, Tár seems free and triumphant because of her scrappiness. She beats up Eliot Kaplan who replaced her and stole her notes, whom Mark Strong plays against type since he usually plays physically intimidating villains. After fumbling to find people to stand by her and a home to rest, her actions reflect that she remembers her earlier words that her home is a suitcase and the podium, her work.

Her story becomes like an ouroboros. Her early career starts in the Amazon jungle and the film ends with her on a boat through another one. In an explicit reference to the mad men in “Apocalypse Now” (1979) and Conrad’s “In the Heart of Darkness,” she finds opportunities in the Philippines. Her Western whiteness carries more value where it is scarce and outweighs her transgressions. Because of her ability to jump into different musical genres and early experience of flourishing in brown countries, she can accept this opportunity and move on quickly whereas her contemporaries would probably refuse or complain about the conditions. Despite her toxic office politics to increase her privilege, she is happier without it. By the end, she is no longer sensitive to noise and can work in a crowded marketplace. She no longer has status, but she has peace. Though disgusted that her predation is no longer cloaked as professional or personal relationships, she is even free to indulge those compulsions. She may come down in terms of prestige, but it is a place where she belongs and can be herself.

If “Honk for Jesus. Save Your Soul.” is the blackest movie ever, this film is the whitest movie ever. The culture is familiar for anyone with intellectual, high art cultural tastes: NPR, The New Yorker, etc. They feel complimentary except Tár is alone in her transgressions so while both films address predation and its consequences, “cancel culture,” “Tár” is going beyond the movie’s explicit question of the work/the artist versus the artist’s behavior. So is there a point besides showing how Blanchett is remarkable and Field can strut his stuff in a genre defying drama?

When “Tár” started, I kept asking myself why a film would make the protagonist into a sexual harasser, but not a man. A viewer would expect the harasser to be a man and dismiss him. One benefit of making the harasser into a woman is our impulse to sympathize and empathize with women as the underdog, especially in a male dominated field, though Tár dismisses her gender as an issue. Casting Blanchett as the protagonist is even better than casting charismatic Sam Rockwell as the loveable racist. It initially fucked with me a bit, especially considering her history with Woody Allen. We are going to root for them regardless of our principles because we like them as people. It felt like a manipulative choice for me to root for a bad guy by making the character into an appealing woman in a male dominated field, and maybe it is so we can imagine a world where we root for the bad guy, but I do not think that it is that simple. Our culture also enjoys destroying powerful women who do not deserve punishment, but I do not think many people will leave “Tár” enjoying her downfall.

“Tár” is about the horror of being a woman and Tár’s inability to escape the societal gender limits when it comes to accessing and retaining privilege. The final glass ceiling is being an awful person and still being supported, not punished. It does not matter if she upholds white patriarchy in hopes that it will return the favor.

Tár identifies as a woman, but adopts a lot of male stylistic choices such as using a tailor and never wearing dresses or skirts. She considers herself dad, not another mom. On the other hand, she is conscious of her image and appearance. Unlike older men with power, she is aware that she is losing her ability to sexually exploit younger women such as the cellist, and even in exile, she is devastated at how being voluntarily desired is not an option as she watches others flirt. Unlike men, similar to younger women conductors, she uses her blonde hair to distinguish herself while conducting and leverages her attractiveness to garner more attention. She retains her gender to defend herself against being called politically incorrect or inappropriate as if being a woman exempts one from human flaws and sins, which is also misogynistic, but she is terrified of being treated as a woman. To her, female bodies are weak, and when she hurts herself, she would rather not admit to human frailty and boasts that she was in a fight. The sequence with her next door neighbors, a daughter and mother in squalid conditions, repulses her but she allows them to command her to take care of them. They feel like a possible future for her, and the first time that we see Tár’s naked body is when she acts as if they infected her and she strips to wash herself off in the closest source of water, the kitchen sink. She avoids visiting her mother in the opening of the film then does not see her when she visits in the denouement, but the dark house echoes her neighbor’s conditions. Even in her success, she is compelled to stay close to her original physical conditions almost as if running from it propels her forward.

Tár oversteps her power. When she preys on women, there is no real backlash, but accusations coupled with video of her bullying a male presenting student appears in the New York Post, she fires Sebastian (Allan Corduner) and attacks Elliot, the momentum builds against her. Destroy women explicitly over email could be weathered, but a woman using her power visibly against men is what vindicates the women’s victimization and galvanizes criticism against Tár.

The way that she treats her predecessor, Andris Davis (Julian Glover), is not reciprocated when her transgressions are public. She worried about him being forgotten, sees him as a father figure and tries to show him respect through money, time and retaining for five years an assistant conductor that she hates. In one lunch, he expresses theoretical sympathy for conductors accused of sexual harassment and is defensive, but when he sees her, he turns away.

“Tár” never takes an explicit side on the artist versus behavior debate, but it does condemn a hypocritical system which protects Tár while it is convenient, but ultimately is more concerned with protecting itself without making any substantial reforms to protect those without power. Tár’s judges are also guilty. The real question is not artist versus behavior—it is why should not a culpable system be punished when it does not even have any redeeming the artist’s redeeming qualities.