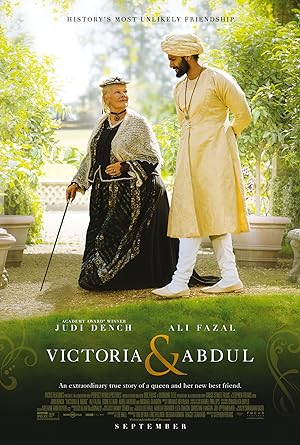

Victoria & Abdul is the unofficial sequel to Mrs. Brown, which I saw in theaters in 1997. Both films depict Queen Victoria’s “friendships” with her servants, and the controversy and backlash that ensued because of the alleged impropriety of a royal and a commoner interacting so closely. Dame Judi Dench plays the titular character in both films, but in her most recent iteration, her biggest fan, Stephen Frears, who directed Philomena, is at the helm. Dench and Frears have a subtle way of telling a story that endears you to certain characters and frustrated with those characters who align themselves with the institution. Spoilers to follow.

Victoria & Abdul is a finely tuned movie, but if you actually think about the story, it is pernicious as it gets you to root for oppression. I paid the admission price by using a voucher when I paid to see another movie with technical problems so I did not feel culpable about contributing to its success and enjoyed the film. Abdul and India act as a frame for the narrative. He is like Belle in Beauty and the Beast. He sees colonialism not as a disruption and possible destructive force in his life, but a window of opportunity and adventure. This colonial system chooses him because he is tall. It is not based on merit or skill, but a biological accident. It is admittedly funny and an early, ongoing joke. If I put on my humorless liberal hat however, it is an early way to groom us to accept unfair hierarchies when they benefit characters that we like by using humor to admit and deflect criticism instead of using the accident as emblematic of an inherently flawed system. Every film does not have to be a screed against oppression, but it also does not have to find ways to excuse it. There are actual studies that show that men may earn $800 more per inch of height. I’m considered average to tall. To some unknown degree, I benefit from something that has no reflection on the quality of my work because everyone tacitly agrees that height is attractive.

In contrast, Mohammed, played by the wonderful comedic actor Adeel Akhtar, who has had a banner year with his supporting role as the married brother in The Big Sick, continuously complains about the inconvenience of his new post. His complaints reveal that they probably did not consent to their new assignment, are removed from their home for someone’s amusement for an indeterminate period of time and constantly provides criticism of British colonialism as barbaric. Akhtar does not deliver Mohammed’s trenchant criticism with humor, but with annoyance; however it is depicted as funny. The film uses postmodern hindsight and embarrassment to make an implicit joke, “Look at these brown people whom the British think are barbarians. They think we are barbarians.” Early in the film, as Mohammed complains of being sick, we think that it is just more dissatisfaction over the disruption, and it is still used for laughs until the Prince of Wales, played by Eddie Izzard, decides to punish Mohammed for his lack of servility to the system by promising that Mohammed will die in Britain, which he does! So retroactively we know that Mohammed’s complaints were not funny, but credible and actually tragically ignored, but the film diverts the audience’s sympathy to the Queen to illustrate how awful her family is.

Victoria & Abdul makes us see Queen Victoria as a person, not an institution, which is fair, but also oversimplifies the situation because she is both. When Queen Victoria is the one wielding the arbitrary or inconvenient power such as not letting people finish their food by eating as quickly as possible, the film depicts it as a joke instead of an aspect of a poisonous, inconsiderate system. Abdul’s adoration of her is shown as her proper due. The film is about empowering her as if an empress needs a boost like Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman, but overlooks that the very thing that hampers her from acting freely is also causing the rancor and racism in her court. There was a study that asked why women are such bitches to each other in the work place, and the answer was that when there is more inequality, instead of being allies, they become competitors and try to undercut each other. So women do not innately make crappy bosses or coworkers. They are reacting to their environment, which provides fewer opportunities to women. They are victims of this system that they uphold.

Victoria & Abdul does disapprove of the racist reaction to their friendship, but their reaction is also consistent with their prior treatment of John Brown, who is Scottish. The hierarchy is rigid and based on absurd rules. Some random chick is queen of half the world that she has never seen by another accident of birth. Even though the film is sympathetic to the Queen, she is still startlingly ignorant of affairs in her own kingdom. The film shows that Abdul exploits her ignorance by being her instructor in religious and Indian matters, but not giving her the whole story, which infers that Abdul’s adoration is a bit opportunistic and gives a dollop of credibility to his detractors. The Queen learned from her prior experience and forgives him for giving her incorrect information ON SHIT THAT SHE SHOULD HAVE KNOWN IN THE FIRST PLACE BECAUSE IT IS HER JOB! She can petulantly demand a mango even though the technology does not exist to get it to her as soon as possible. Her court is understandably angry at her capriciousness and delinquency, especially considering that they have cosigned a system that the Queen is whimsically subverting based on favor, not the rules of birth, race, country of origin, profession. If they cosign the system, they expect to be rewarded by the system and expect the system to be governed according to its rules, but because they cannot direct their anger at her, the head of this symbol, though they try, they kick the dog.

The filmmakers conflate the institution with the people who are vocally enforcing it, but conveniently overlook the fact that Victoria is a crucial part of that institution and not simply, to a certain degree, a victim of it. Victoria & Abdul uses the Queen rallying for a brown man to validate her power and prove that she should rule over them because she is innately better than them to appreciate someone adoring her regardless of race, status or country of origin. His adoration of her and his acceptance of her reprimands also reinforces that she should rule over him and alleviates her of any accusations that she has no business being in charge of India. The discussion of a fatwa or Muslim outrage at her rule may be rooted in historical fact, but when the audience is told this, we see Dench’s face, a face that we love, an elderly woman. The normal reaction to this news is to feel sympathy for her because we are human, and we love her, not to see it as a reaction to her as the symbol and head beneficiary of colonialism.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.