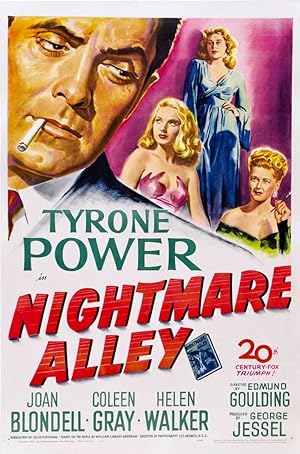

“Nightmare Alley” (1947) is the classic Hollywood adaptation of William Lindsay Gresham’s novel about an ambitious carnie’s rise and fall. Edmund Golding directed and is best known for “Grand Hotel” (1932) and “Dark Victory” (1939). Jules Furthman wrote the screenplay and often partnered with Howard Hawks and Josef von Sternberg. Most people believe this film noir is superior to Guillermo del Toro’s 2021 cinematic adaptation, and it is probably more faithful to the novel, but I have zero interest in reading it so I will never know. Normally I find the original superior, but del Toro wins this round. Classic movies had to self-censor (look up the Hays Code) to remain commercially viable, and this version pulled quite a few punches. I saw del Toro’s film on the big screen so the classic cannot compete. The studio head still found it so disturbing that he took it out of circulation after it performed poorly in the box office, but it was rereleased a decade later to great acclaim. The following is a comparison of the two films, and less a review of the earlier film.

del Toro took his time to develop each character and set the stage whereas the classic starts long after Stanton Carlisle (Tyrone Power in his first villain role) has been working for the carnival and races to the denouement. The protagonist’s past is vague: an orphan stuck in religious institutions. He is not homicidal, but more overtly selfish with a guilty-conscious. Men are more hostile to him for his looks, curiosity, and accomplishments even when he serves them, but their suspicions are vindicated. The classic version of Stan does more foreshadowing parallels of Stan and Pete and is a shameless womanizer.

Bradley Cooper’s version is more sinister and innocent. Powell’s different era acting style cannot compete with Cooper’s version—a man plagued with self-condemnation. Combined with his performance in “A Star Is Born” (2018), Cooper’s trademark is a devastating portrait of unresolved trauma and descent into alcoholism. Powell’s Stanton’s ambition is borne of wounded pride when the carnival forces Stan and bruises his ego. He then resents his carnie roots whereas Cooper’s version sees them as his family surrogate, a happy alum. Powell does transform into a slurring mess and resembles Pete, but if things were different, he would have never considered leaving the carnival.

The doctor’s motives make less sense. Whereas del Toro’s Dr. Lilith Ritter (Cate Blanchett) seems competitive and vengeful, the emphasis in the classic is on her first name, which evokes women’s innately fallen nature. Her professional attire and lack of obedience to gender norms marks her as an aberration. Each woman in this film is trouble. Zeena (Joan Blondell) was a professional and personal cheater long before Stanton appeared. She grows to resent Stan. Even Molly ruining the act is an expected betrayal though she is performing her wifely duty in protecting souls. By being framed as a sexually precocious teen instead of a mark, Molly is a temptress.

del Toro’s women characters are survivors. Dr. Ritter survived parental psychological abuse and physical abuse with the implication that her father may have sacrificed her to save his skin or failed to protect her in exchange for power. Blanchett plays the psychologist like Michelle Pfeiffer’s Catwoman. Zeena (Toni Collette) stands by her alcoholic husband out of loyalty and cheats to cope with his spiritual absence. Despite her age, Molly (Rooney Mara) is a wide-eyed, inexperienced innocent because of daddy issues and rape. It explains why Molly is so angry when she figures out that Stanton is rotten. Mara’s version gets a better ending though she may have become what she hated. She gets what Blondell’s character tried.

I preferred the classic Molly (Coleen Gray) at the carnival. Gray evokes Rita Hayworth and combines burgeoning sexuality and confidence from being a baby conman with naivete and innocence from lack of actual experience like Suzanna Son as Stawberry in “Red Rocket” (2021). Gray plays Molly as someone unruffled and believing that she can handle anything until confronted with a challenge whereas Mara plays her as someone who gets stronger with time and firmer in her convictions, but always tended to screw up the act. Both interpretations work, but the prior felt more genuine, and the latter felt like a virgin whore dichotomy.

The sideshow attractions pull punches. The geek’s audience’s reaction is shown and heard, but the geek is not visible. The world outside of the carnival is less demented and is a stand in for ordinary folks despite wealth and power in the classic version whereas del Toro’s version makes the world worse. It makes sense that classic Hollywood would not want audiences to question authority whereas we live in more cynical times so we know that power and corruption usually come in pairs. del Toro’s Stanton becomes like Gray’s Molly—someone who has bitten off more than he can chew. Classic Stanton is a blasphemer who must be punished. The novel extends the “spook show” to becoming a charlatan radio preacher. Apparently the novel and movie inspired Anton LaVey, especially the emphasis on Tarot.

If the 1947 and 2021 stand on equal footing, it is in the casting of Pete, Zeena’s husband, the fallen alcoholic mentalists. Ian Keith and David Strathairn are vocal twins. The 1947 film surpasses del Toro’s with the possibility of multiple bleak endings. While Dr. Ritter’s motives are inscrutable, her psychoanalysis cover story explicitly alludes to the title and makes a credible argument for Stanton being delusional. I enjoy the ambiguity of her deceit, and the idea of an alternative ending with him still ending up in a strait jacket. The denouement pulls punches, but I did wish that del Toro’s version revisited the original carnival. It would have been so much bleaker to have former associates as tools of dehumanization and destruction. They already showed sinister seeds in the way that they protected Molly. While the first adaptation does not use the same carnival associates, the redemptive ending makes it feel as if it was considered. The final boss is not Hoatley and is unnamed, but a less observant viewer could accidentally conflate the two.

The 1947 ending is supposed to be redemptive because women are expected to sacrifice their lives for eternity to a husband regardless of quality in exchange for love, but in today’s context, the end is almost as frightening as del Toro’s except for women. Gray’s Molly becomes Zeena in the worst way possible: trapped in a dysfunctional marriage, a servant and bread winner with little to no legal freedom from a man with no judgment.

The 1947 film seems like a cautionary tale for everyone. Don’t have sex outside of marriage because then you will be saddled with the worst guy forever. Don’t have an affair or else you will be alone and unsuccessful. Don’t be an alcoholic or you could end up physically or spiritually dead. Don’t play God or you will become a beast, Nebuchadnezzar. Don’t worship false gods like Saul or you will be swindled out of your money and humiliated. Only two characters emerge unscathed: Bruno and Dr. Ritter.