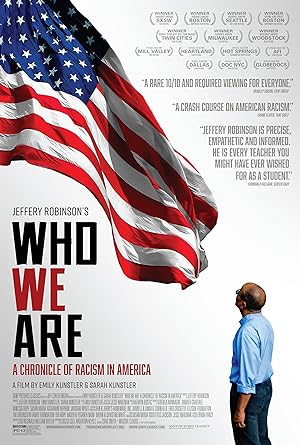

Sister documentarians Emily and Sarah Kunstler’s “Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America” (2021) was filmed In New York on Juneteenth 2018. It is a film adaptation of a talk that Jeffery Robinson, a criminal defense lawyer, former ACLU Deputy Legal Director, and the founder of the Who We Are Project, gave for over ten years to educate audiences on American history and the role that government played in perpetuating racism for financial benefit. The timing of this film adaptation is perfect since Robinson’s ability to safely deliver this talk has diminished with the pandemic.

“Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America” is more TED Talk than Raoul Peck’s vigorous and rousing “I Am Not Your Negro” (2016). A TED Talk is shorter so viewers with limited attention spans may not feel the full impact of Robinson’s message. Robinson believes that if people learned the truth about American history and how it put Black people on an uneven playing field, we could finally move away from the “tipping point,” the moment where racial progress begins its Sisyphean backwards slide if all Americans are unwilling to make a final push. Robinson’s examples of past tipping points are Reconstruction and Jim Crow and the twentieth century Civil Rights movement ending with the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and beginning with Nixon’s rise and the war on drugs. The film rushes to draw parallels with our own time without explicitly stating what is triggering the reset to America’s default settings. This documentary may not convince anyone of the existence of state sponsored white supremacy for financial gain though it is well researched and grounded in the opposition’s rhetoric. It is a preach to the choir documentary because the title alone would not convince anyone in opposition to watch it.

“Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America” is framed as Robinson arguing his most important case, but who is the judge? It is white people, and the film gives viewers two types of people to choose from: the one guy fighting for Confederate statues or Robinson’s friends. Robinson reluctantly agreed to the Kunstler sisters’ request to use his personal story as bookends to the film to sway viewers to fight against racism. Robinson sees his fate tied to Larry Paine, a teen that local Memphis cops murdered after a protest on March 28, 1968, which Robinson and his father also attended. If viewers can get invested in Robinson’s personal story of success despite state sanctioned obstacles to prevent his advancement, then maybe he can humanize Paine and others murdered in extrajudicial executions by suggesting that they were not different and sliding some of his favor to them. Robinson was vulnerable to institutional racism, but because of a handful of people who chose to intervene and help him integrate schools and neighborhoods, he could have the American dream. The film includes a scene where one family friend states that she was unaware of his family’s difficulty with the neighbors after integrating it. Even for Robinson, how deep are these relationships if allies are oblivious after taking a single action? Even the good guys fall short, but the film does not explore this nuance. The film does not rest in this uncomfortable truth that even people who are proactive in the fight against discrimination do not have the staying power to continue the push and are closer to a one and done model. While Robinson highlights MLK’s quote contrasting easy wins with a willingness to sacrifice and pay a price, the film does not explore how that plays out in Robinson’s life even though the opportunity presents itself.

In the tradition of the historical civil rights movement repurposing Christian culture to persuade the public, Robinson uses evangelical persuasive techniques to try and turn us away from doomsday, another tipping point. Robinson believes everyone and our nation can be saved despite an early scene showing the opposite with Braxton Spivey, a pro Confederate statue protestor. Spivey ends up arguing that even though he would not like to be enslaved, and slavery is evil, if the economic system permitted it, and he was treated well, slavery would be fine. “Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America” calls on viewers to repent of the country’s original sin, slavery, and ask the viewers to act like his family friends.

“Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America” cuts between clips from Robinson’s speech in New York, his on-location interviews with local historians, the relatives of people extrajudicially executed and his friends and family, historical archival footage, and photograph montages. The actual arrangement of the information is somewhat counterintuitive. His speech is chronological, but when the film starts jumping to on location spots, it begins at the end with confederate statues, interviews with Terrence Crutcher and Eric Garner’s relatives and a former Obama staffer who got harassed on moving day after a neighbor calls the cops. The film is trying to make a point regarding how rhetoric has a real-world effect, and that rhetoric stems from a long-standing government institutional cultivation for financial benefit. Considering that the film would later return to those issues, that footage placement should have come later. It is understandable that the filmmakers prefer to draw in its audience with recognizable issues instead of just dry history, but the Presidon’t quote on Andrew Jackson worked more effectively to propel us into the past before jumping forward. Whereas Peck knew how to breathe life into words, the Kunstler sisters let Robinson take the lead, but he is a lawyer. He deals in words, and they needed to find a way to translate his words into images. Just putting text from the Constitution or various historical primary sources on screen is not sufficient.

At one hour fifty-seven minutes, “Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America” has some valuable moments for any viewer, including those who need no persuasion, that can get lost with the amount of telling, not showing. When the film focuses its story solely on chronological events and shows the surviving family members or witnesses of historical lynchings or massacres, it brings history to life and makes it seem less distant. Robinson interviews Josephine Bolling-McCall, author of “The Penalty for Success,” whom I saw speak in person on March 6, 2020 at the Old South Church in Boston about her father’s murder, and Lessie Benningfield Randle, a survivor of the Black Wall Street Massacre. These women speak about what they witnessed, and they were the most powerful moments in the film. The lack of consequences to outright murder without the usual dance between the murderer’s cover story of fear and the push to humanize the executed who are deemed guilty for existing. Their experiences combined with newspaper reports and photographs from that time makes the point in a way that does not make their stories as vulnerable to demonization as contemporary stories. Even in an era of pushback and rampant murder, there was less rationalization.

“Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America” is a diplomatic movie that could be used as an introduction to American history, but lacks the visual richness that the medium demands.