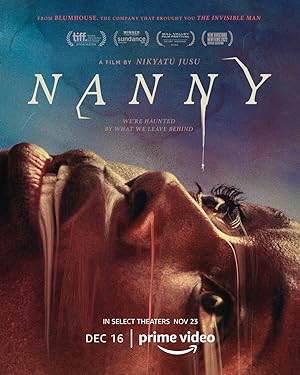

Writer and director Nikyatu Jusu makes her feature debut and won the Sundance Grand Jury prize for “Nanny” (2022). Senegalese immigrant Aisha (Anna Diop) works in the titular profession so she can send money to her cousin, Mariatou (Olamide Candide-Johnson), who is taking care of Aisha’s son, Lamine (Jahleel Kamara). Aisha’s goal is to earn enough so she can afford plane tickets so her son can join her in Manhattan. As she works for the family, she begins to have bad dreams, disassociate, lose time, and hallucinate. Why is her mental state deteriorating?

When “Nanny” starts, Aisha is hopeful, engaged and friendly. Diop does a great job holding the film’s focus and getting viewers invested in her character even as she shows her less personable traits. Though Aisha is an unreliable narrator, Diop grounds her with dignity, calm and resolve so we are willing to go on the journey even as Aisha’s mental state deteriorates. Initially things look promising. Aisha has a job taking care of a great kid, Rose (Rose Decker), has a roommate and friends that care for her and meets a great guy, Malik (Sinqua Wells), whose family loves her. It is a vibrant, colorful and gorgeous film that reflects the spirit of the woman at its center, but there are literal and metaphorical shadows that start moving out of the corners and demand attention.

“Nanny” is an ambitious film that contrasts how Aisha exists in the world with equals and how others’ outside of her community, particularly her employers, Amy (Michelle Monaghan) and Adam (Morgan Spector), try to treat her as a supporting character as if they were the stars. So as Aisha’s personality starts changing, there are a panoply of possible explanations: psychological strain from being separated from her family and spending too much time with her problematic employers, being monitored, spirits, a scientific explanation or something else. Chief is the guilt of being an unwilling absent parent while caring for someone else’s child without having the freedom to treat that child in the way that you see fit. Because I watch too many films, I thought the answer was obvious and was mostly right.

“Nanny” touches on provocative themes of mental illness, sexual double standards (pedophilia and victim blaming), financial exploitation, microaggressions, feminism and the hypocrisies of liberal men and women’s ideals versus practices. As each theme gets introduced, I got excited at the prospect of Jusu tying everything together, but the intriguing elements remain disparate and never form a cohesive whole. Eventually the supernatural elements increasingly dominate the protagonist and overshadow these themes, which get lost with a pat denouement happy ending that somewhat cheapens what preceded it. Aisha gets her American dream.

“Nanny” is billed as a drama and horror film, but it may have worked better without the supernatural elements. The film feels like a reprise of Ousmane Sembene’s “Black Girl” (1966) set in New York City instead of France. Unlike Diouama, Sembene’s protagonist, Aisha is less isolated, and there are wonderful scenes between her and other people of the African diaspora such as Africans from other countries, Americans, Caribbean. Unlike the French, Americans are not traditional colonialists, but they do inherit an uncomfortable, intersectional mix of privilege and disadvantage. Amy and Adam try to be warm towards Aisha, but as employers, they have more in common with Lady Dent in “Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris” (2022). They play as if they are in the big time and enlightened by having a black friend and knowing about international social justice issues, but they try to make Aisha sympathize with their problems so Aisha will agree to be their slave, which Aisha rejects and expresses her anger.

When “Nanny” introduces the supernatural themes, Anansi and Mami Wata, a water spirit who predates traditional concepts of mermaids, Jusu clearly has a vision of how the dual nature of these folklore figures ties into the protagonist’s plight, but it was not clearly conveyed to the viewer. Though Malik is a full, three-dimensional character, he is an excuse for Aisha to meet with his grandmother, Kathleen (Deadpool’s Leslie Uggams), a psychic who guesses what Aisha subsequently reveals—her family believed in these forces and now she is seeing them, but she cannot discern what role they play in her life. Anasi felt like an afterthought so Jusu could use spiders. Mama Wata works a little better since water imagery is present in the language and imagery of the narrative.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

I kind of guessed right about how “Nanny” would explain Aisha’s psychological problem. I thought that her son Lamine was always dead, but she was in denial. When the black mold in the room at her employer was revealed, I began to root for Aisha to be suffering from mold induced psychosis, aka toxic agoraphobia or mold toxicity, but alas no.

“Nanny” was frustrating in the way that it introduced then dropped characters. We never see Aisha’s roommate again, and her only purpose is to stress how important it is that Aisha keeps her job. The cousin gets brought to the US never to be seen again, but to deliver devastating news. What!?! When she blames Aisha for Lamine’s death, yes, we understand that it is the employers’ fault for not paying Aisha, but those are fighting words that would destroy a relationship forever, especially considering that she waited to tell Aisha that her son was dead! A film cannot introduce an asshole cousin then just drop it. She did not have to be framed as a jerk, or the film needed to grapple with it more. I do not see Aisha letting go of the money for two tickets and her son dying on her cousin’s watch.

I hated the ending of “Nanny.” She is pregnant and happy, but um, that would not erase everything that happened before. A new baby does not replace a lost child. Part of the legend of Mama Wati is that people can be calmer after they encounter her, and Mama Wati bestows fertility so maybe the film was trying to say that Mama Wati gave her this happy ending so she would not break, but it did not work for me because it still had the effect of erasing everything that came before.

Normally if a film has a black woman protagonist, I am only invested in her story, but even though I was on Aisha’s side and understood that she was not responsible for her lapses in judgment and psychotic episodes, I became more concerned about Rose and Malik. Just because Aisha is not at fault, it does not change the fact that she almost stabbed a child. Rose becomes a parentified figure reassuring Aisha and validating Aisha’s supernatural experiences. Regardless of intention or responsibility, Aisha has traumatized Rose-a theme touched on in “Smile” (2022). At some point, “Nanny” could be cut as a short film about a child witnessing mental illness and being helpless to communicate it to others, especially considering that her parents are going through their own separate crises, particularly her mom who is sinking into depression and alcoholism. I was also concerned that Malik was romantically attracted to a mother figure with mental issues. Um, he is replicating his childhood trauma. I love Aisha too, but the film kind of glosses over the complicated theme of how unflawed Aisha damages other innocents around her so ultimately the film did not work for me.