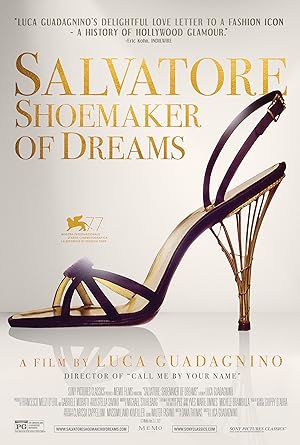

Luca Guadagnino’s first feature length film was a documentary, “Bertolucci on Bertolucci” (2013), and he returns to his cinematic roots with “Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams” (2020). The title borrows from Italian shoemaker Salvatore Ferragamo’s autobiography, “Shoemaker of Dreams: The Autobiography of Salvatore Ferragamo,” and Guadagnino possibly adapted huge portions of it in this authorized biographical documentary in which the Ferragamo family and business appeared to cooperate fully. Guadagnino chronicles Ferragamo’s life story from his humble hometown in Bonito Italy to the heights of the Hollywood Hills and finally Florence Italy where he became an international success.

I am into fashion documentaries, and I have a great track record of watching all of Guadagnino’s feature length films so I was eager to see “Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams.” Fashion and shoes are two different things, and though I could intellectually appreciate how people would enjoy this film, it lost me once it began to focus more on his work than the genius survivor behind it. I had to struggle to make it through the film.

Because “Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams” is an authorized biography, Guadagnino has exclusive access to Ferragamo’s home videos, the site where the shoes are crafted and archived shoes dating as far back as the early twentieth century. It also means that exclusivity requires sticking to the family’s narrative of their beloved patriarch, and Guadagnino never strains against the restriction. He seemed entranced and visually, his scenes depicting the family resembled his work in “I Am Love” (2009). Also at the time of filming in 2018, there are so many family members who knew Ferragamo first hand, including his wife, Wanda, that it is easy to understand the allure of following their lead.

“Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams” is strongest when focusing on the precocious boy obsessed with feet, begging for permission to become a shoemaker’s apprentice. His career begins in earnest at ten years old after his father dies, and he must start working. Too young to know better, he is filled with confidence after a stint in Napoli and strikes out on his own. He is an immigrant who believes that he deserves better than most expected and possessed a vision of how to make that a reality. When he follows his brother to the US, he views the factory system of Boston as an abomination (“I was not impressed. I was appalled…far below the standard that I had set for myself. That was no place for me”) then makes his way to California where he starts to work with film studios during the silent film era. Ferragamo is such a shoe fanatic that he goes to the University of South California to learn about foot anatomy, which explains how his shoes were beautiful and comfortable. (Meant as a compliment: was Ferragamo autistic and feet were his special interest?)

Like “Suspiria” (2018), Guadagnino divides the narrative into sections with location intertitles, but they are flourishes ungoverned by a narrative rhythm. I loved the opening credits being paired with a behind the scenes look at his shoemaking process thus giving credit to his workers. Guadagnino brings the story to life using Ferragamo’s voice and words from audio recordings so it feels as if he is confiding to the audience. Frequent Guadagnino player Michael Stuhlbarg (whom I have a huge crush on) also brings Ferragamo’s voice to life, but documentaries should establish one rule. When the original, distinctive voice is available, only use the original or a voice who can sound like the original. An Italian actor would not have taken us out of the reverie. While talking head experts such as writers, historians, famous contemporary shoemakers and Martin Scorsese musing on the immigrant experience add color to the story and will attract butts to the seats, I would have been satisfied with Ferragamo exclusively telling his own story.

“Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams” serves as an unofficial historical account of the silent film era with shoes as the entry point. Guadagnino’s detour may attract film historians as he shows the emergence of the star system and the move from Santa Barbara to Hollywood because of taxes. Normally I would enjoy this detour, especially since I have delved into the early black and white Biblical epics, which Ferragamo worked on, but because my mind was focused and looking for Ferragamo, I felt my interest flagging in the documentary and wondered when we were going to get back on track. The name dropping did not work for me. It makes sense that a filmmaker of Guadagnino’s stature would make such a detour, I wanted more focused. The denouement ends with an animated sequence of Ferragamo’s shoes as if the shoes were Busby Berkeley’s chorus girls.

When “Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams” returns with Ferragamo to Italy, it acknowledges emerging fascism, and how Ferragamo found inventive and innovative ways to survive trade embargoes against Italy during World War II, but does not address Ferragamo’s politics. Guadagnino’s films often allude to oppression and leaves its traces in the corners of his films, but never faces it head on. “Suspiria” unfolds around the Berlin Wall. “Call Me By Your Name” involves Jewish Americans openly navigating an Italian countryside which would have been hostile to them decades earlier. Here the omission is deafening. Every human being has flaws, and Ferragamo always found ways to get around financial government rules, but how far does that legal flexibility run? If he was saving people, I am sure that the documentary would have led with that so the fixation on his inventiveness tells another story. We will never know.

As “Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams” approaches the end, it gets repetitive and returns to reveal the production process and meditate again on his ability to help the wearer balance on stilts. The film tries to evoke magical realism by referencing international fairy tales and legends about shoemakers as magicians. In Ferragamo’s own words, he did not learn how to make shoes, but remembered, thus implying reincarnation. If this thread ran throughout the entire native, I would have loved it, but there are only tantalizing, intermittent sprinkles.

“Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams” spends a little time at the end meditating on how Ferragamo and Christian Dior crossed paths, which seems like a possible sequel idea. Dior relays the story of winning the Neiman-Marcus Award for his New Look and coming to Dallas in “Dior by Dior: The Autobiography of Christian Dior.” Despite their differences, their styles drank from the same river as postwar fashion designers who survived. It was a great way to tell Ferragamo’s story using an equal, but not a competitor whereas everyone else is a customer, family member or an admirer. It lends credibility to his story.

Despite pacing issues, I will leave with the inspiring words of Giovanna Gentile Ferragamo, his daughter, “I remember he often told us that if there was something we had undertaken, that we had started doing, or wanted to do, and we’d found obstacles or encountered difficulties, we should never, never leave it unfinished but go all the way first and then decide if we wanted to continue or not.”