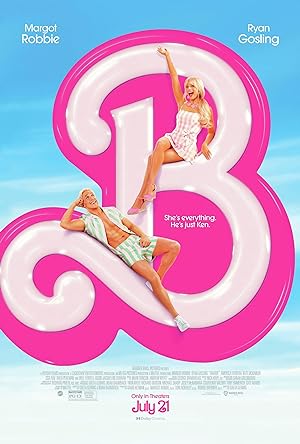

“Barbie” (2023) is the first live-action Barbie film, but it is not a kid’s movie. It is for teenagers and adults who enjoyed playing with Barbies but have outgrown them and are tackling life’s complexities. Stereotypical Barbie (Margot Robot) loves living what she believes to be a perfect life in Barbie Land with different variations of Barbies and Kens. Barbie Land is like the Real World but obeys the rules of play physics. For instance, Barbies float from their houses and experience the sensation of drinking and showering though no liquid is involved. When Stereotypical Barbie experiences existential dread and falls instead of floats from her home, Weird Barbie (Kate McKinnon) diagnoses her as malfunctioning and instructs her to journey to the Real World to cure it by finding the person playing with her. Ken (Ryan Gosling) stows away in her convertible. Barbie and Ken experience the Real World in such different ways that they want to change the way that they live, but these opposing epiphanies lead to conflict over how their society should function.

Greta Gerwig directed and co-wrote “Barbie” with Noah Baumbach. In April 2022, when studios announced that “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” (2023) were going to be released on the same day, it was no contest. I prefer Gerwig, especially “Lady Bird” (2017), over Christopher Nolan, who has dominated the summer box office until the pandemic, which was not entirely his fault, but that is a story for another time. Gerwig may be the underdog, but she makes better movies by choosing character development over exaggerated spectacle. Cut to a little over a week after its release, my prediction is fact. “Barbie” is outpacing “Oppenheimer” at the box office. While she may not have a signature visual style, Gerwig’s stories center women on a journey of self-discovery. With financial backing, she proves that she can still bring to life a stylized, colorful world without losing the ability to tell poignant stories. In a commercial venture, Gerwig expresses the yearning and options that the doll symbolized in childhood.

“Barbie” feels like Gerwig’s “Beau Is Afraid” (2023) except successful at achieving her goals. Her film is more approachable since it unfolds on a cultural common ground, the iconic doll that girls have been playing with since 1959. A viewer does not have to discern the rules that govern this universe because they probably already know them. The relationship between Barbie Land and the Real World leads to a surreal, fantastic yet familiar universe with a little dash of the supernatural. Like “Asteroid City” (2023), Gerwig uses the stylized Barbie universe to reflect on the nature of human existence and our society’s shortcomings. Gerwig sees “Barbie” through a disillusioned lens of someone growing up looking forward to life, but life’s drawbacks are overwhelming; however, the depth and range of emotion makes life worth it. It is an ambitious movie that also tackles gender norms, social contracts, privilege, and politics.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

“Barbie” is about trade-offs, and the narrative’s path starts with the illusion of perfection later exchanged for authentic existence. The film is divided into three acts: obliviousness/childhood, awakening and action. Barbie does not want to leave childhood and prefers ignorance because who wants to lose privilege. Even though Barbie Land is playful and pink, it still has its issues and is far from a utopia. Most of the Barbies ridicule anyone who is not in mint, original condition such as Weird Barbie by equating appearance to character, and there is constant tension among the Kens who vie for Barbie’s attention. It may feel like a feminist utopia because the Barbies are in power and able to embrace their femininity without internalized misogyny, but the existence of an underclass indicates otherwise. Gerwig’s story strives to achieve true feminism, which means being an individual who is not defined by external attributes or exists for another person. In a world of Barbies and Kens, be an Allen (or Midge, but being eternally pregnant sounds like a nightmare).

Throughout the course of the movie, Barbie loses everything: her perfect body, her home, her relationships, and her legacy. As Barbie begins to experience shame and disgust over her physical transformation and question the aesthetics of her world, she is in for more shocks because her image of the Real World is dissonant from her expectations. Real World women deal with patriarchy, objectification, and the specter of violence. In the Real World, Barbie is an outlaw, a wanted person, not only for a comic misunderstanding about money, but for defending herself. Being a woman is innately transgressive even if that woman is a doll.

The Real World antidote to Barbie’s ills is an unexpected twist. Gloria (America Ferrera) and her daughter Sasha (Ariana Greenblatt) rescue Barbie while Barbie’s existence instills hope and happiness in them and evaporates cynicism by realizing Barbie is real, and there can be a comparatively ideal women’s world. Gerwig plays with the duality of Barbie as an eternal idea, and human beings as a finite existence, but the human beings represent the idea of resistance to and tenaciousness against oblivion of the spirit and the body. The antidote also becomes a problem as the rest of Barbie Land becomes infected with Real World problems.

The offscreen transformation of Barbie Land was frustrating. It is easy to accept because it is our norm, but I wish that Gerwig gave us a glimpse of how it happened. Then the final act would feel more balanced. I understand that Barbie is the protagonist on her own journey, but the film detoured and followed Ken so with a scene or two more, it could have felt more cohesive. How did he brainwash all the Barbies to become objects to the Kens, subservient objects?

“Barbie” feels like a pointed response to the world post-2016 and the resurgence of explicit government institutional suppression of women’s rights. Yes, “Barbie” is an angry movie. Barbie Land in crisis becomes a satirical take on post-2016 US Presidential election: coups, law changes, power grabs, even the erection of a wall. The final line is hilarious, but as gynecologists are basically outlaws in a majority of the country, going to one becomes a revolutionary act of bodily autonomy. Greta only shows the cure, “By giving voice to the cognitive dissonance of living under patriarchy, you robbed it of its power.” The transition between the final two acts is the image of Barbie just lying face down, which reminded me of Saturday Night Live ‘s Tina Fey sheet cake segment on Weekend Update. Paralysis in the face of increasing obstacles was not an across-the-board representative response for all women, and not all women were brainwashed. They cosigned patriarchy, which is why I suspect Gerwig decided to use a high-profile, political woman (of color?) actor to deliver that speech.

While the film’s casting is inclusive, Barbie Land is a deliberate, self-aware commercial flat version of whiteness as a product. There are different races, but no ethnic culture outside of Barbie Land. Even if there were no Barbies of color, there would be no French or Italian cultural Barbie. Barbie is the culture similar to how moving to the US often requires an assimilation devoid of origin. Like “Paris Is Burning” (1990), “Barbie” engages with the fantasy of whiteness, the promise of a dream denied: rooted in consumerism, image, and superficial community. It does not feel like an accident that Barbie is most invested in her Dream House. Work and accomplishments are vague concepts embodied in physical appearance though Gerwig does show the Barbie variants in action as lawyers and doctors, but she reserves Stereotypical Barbie’s visceral rage at being robbed of her ownership of her Dream House, belongings, appearance, and leisure time with others.

Gerwig has a personal, cultural ax to grind at any man who wanted her to passively admire them instead of coming together to enjoy a mutually agreed upon activity. “Can you start the movie again and talk through it?” There is real anger at how women are in a double bind, i.e. trying to live up to conflicting, mutually exclusive expectations and how that plays out in times of leisure. Even before Barbie’s awakening, Gerwig mines the humor out of Ken’s desperation to become a part of Barbie’s life and Barbie’s disinterest, “I don’t want you here.” Ken’s parallel journey occupies a huge part of the film and felt incisive in its depiction of a “nice guy” or a “liberated man.” There are two minor positive romantic relationships, otherwise Gerwig’s Barbie rejects the burden of men’s insistent demand for attention and relationship. Men’s freedom lies in no longer seeking attention, competing, and appreciating their existence as an individual.

While Gerwig’s latest feature may be a cri de coeur, “Barbie” can be a bit didactic in the way that the monologues and dialogues mimic academic analysis when discussing Barbie Land’s predicament, but it feels earned and balanced. It improves with repeat viewings. The more pedantic it becomes, the more that Gerwig rewards us with outlandish musical numbers with the Kens’ idea of war, and the Ken with the most magic, which seems to emit from his chest in an array of sparkle stars like a Care Bear, becomes the leader. Michael Cera as Allan may have given his best performance to date, and if he got a spinoff movie, I would not be opposed.

“Barbie” references so many movies such as “The Matrix” (1999), “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968), “Sorry to Bother You” (2018). I loved how the film signals which era was formative for Gerwig with shout outs to the Indigo Girls “Closer I Am to Fine” and Colin Firth’s “Pride & Prejudice” (1995). I also felt as if there was a slight nod to “Wonder Woman” (2017) when the Barbies rescue Ken, and he notes how strong they are. Also in the first travel sequence, Stereotypical Barbie never breaks into a sweat, but Ken struggles to keep up and pretends to be at ease. There is a slight danger that the movie could have tipped into spoof territory, but Gerwig keeps it on course.

“Barbie” is also an ode to nostalgia and appreciation for Mattel’s universe, which may explain why Gerwig stumbles in her on-screen depiction of the company. Gerwig fails to flesh out the middle ground, the fictional, on-screen machinations of Mattel as a shady corporation, private corporation in liaison with the government to guard the portal between the two worlds. While Will Ferrell, who plays the CEO, uses his comedic talent to cover the lack of thoroughness and detail in Mattel’s machinations, it is hard to say what role that they are supposed to play. Because they occupy a murky middle ground between Barbie Land and the Real World, they also appear like villains, but also seem to want to preserve and protect Barbie, but I had no real sense of what their idea of success looked like. What happens in the Box? It is implied that they will help seal the rift between Barbie Land and the Real World, which is not the point of the story. The focal point is Stereotypical Barbie’s ending.

The narrative structure of “Barbie” is intriguing. Helen Mirren narrates and is telling a story to an audience thus breaking a fourth wall without puncturing the viewer’s ability to be swept away by making them too conscious of the process of watching a movie. Whenever the story verges on straining suspension of disbelief, Mirren’s voice explains/mocks it and allows us to laugh through the fissure. The beginning of the film strikes a satirical poke at Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968) opening sequence. Instead of man’s origins and evolution, Gerwig commences with the beginning of girls at play and their evolution. Instead of hominins, the tribe only consists of little girls playing with baby dolls. An enormous Barbie replaces the mysterious monolith. Gerwig further deviates from Kubrick’s narrative by not jumping forward in time to follow the effect that Barbie had on human girls, but presumably the effect that those girls had on Barbie. She moves from being alone and a singular monolith to masses of Barbies and Kens living in Barbie Land.

In the mythology of “Barbie,” there is a creator, Ruth Handler (Rhea Pearlman). Though it is not explicitly spelled out, her imagination is powerful enough to create Barbie Land, and her spirit occupies the seventeenth floor of Mattel. She is the Creator, and though not God, as close as Barbie gets to one, but Handler is dead and attests that there is no deeper supernatural order other than the one that she created. Handler then Mattel, the corporation that owns the rights to Barbie, populate that land with their creations: Barbies, Kens, Allan, Midge and any other products, including accessories and clothes. These creations mistakenly believe that they have made the world a better place, but the magical effect seems proportionate to their interaction with the Real World, specifically Mattel and the people who play with them.

Barbie Land seemed a bit horrifying to me: a never-ending loop of superficial pleasantries, lack of privacy and a hell of eternal sameness, “It is the best day ever. So was yesterday, and so is tomorrow, and every day from now until forever.” It felt like the cheerful flipside of “The Shining” (1980), which is later referenced, “Come play with us, Danny. Forever…and ever…and ever.” No wonder death seems like an escape. Stereotypical Barbie’s journey is to leave the horror of the commercial idealistic image and become a human being. When Ken hits the Real World, he absorbs images, specifically Sly Stallone in a fur coat, whereas Stereotypical Barbie sees people experiencing a spectrum of emotions, including genuine male friendships, a man expressing sadness and starts to exhibit them.

In retrospect, the narrative trajectory of “Barbie” is predictable. Once Stereotypical Barbie faces that things always change, even in Barbie Land, she wants to become real, feel and find out, “What Was I Made For?” “I want to be a part of the people who make things, not the thing that’s made. I want to do the imagining.” This melancholic desire is embedded with death and disillusion, but her consent is informed. She becomes the second coming of Barbara Handler, the namesake of Ruth’s human daughter, the inspiration for her creation.

I was fascinated by the liminal spaces that Stereotypical Barbie and Ruth occupied. The infinite, cold hallway of the seventeenth floor leads to a warm kitchen. James Turrell’s work felt like the inspiration for Ruth and Barbie’s final scene together before she becomes real. We have a visceral understanding that these spaces convey eternity, an in between world that exists outside of time and space. Dolls have souls and autonomy with a value comparable to ours. Even if human beings end at death, we exist as gods in the spirit of our creations.

(So I do not culturally appropriate, I am begging an expert to write about Barbie as a golem. Please and thank you.)