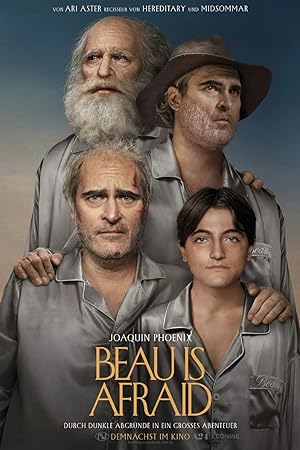

“Beau Is Afraid” (2023) is director and writer Ari Aster’s third feature film, which he describes as a comedy. The film shows the world through the perspective of Beau (Joaquin Phoenix), a chaotic place filled with danger and fleeting moments of comfort. It starts with his gestation, segues to him as a grown man steeling himself to visit his mother. A visit to his therapist toys with a theoretical thought exercise in wish fulfillment then becomes a living nightmare as mounting obstacles prevent him from being at his mother’s side. It is an expansion of one of Aster’s early short films, “Beau” (2011).

I love Aster and his horror films, “Hereditary” (2018) and “Midsommar” (2019), which I watched repeatedly in theaters. His horror films start with death, which his protagonists handle poorly because such is the innate nature of grief, but also because of mental health challenges that they and their families struggled with long before anyone died. In “Hereditary,” the spectre of a domineering, cult mother influences the entire movie. In “Midsommar,” there is still a cult, but the family’s connection is implied, but uncertain though they make postmortem appearances in rituals. Similarly, the backdrop of “Beau Is Afraid” is the subordination of all desire and functional needs to serve Beau’s mother, who is a cult leader in her own, secular way. While Beau’s indecisiveness and weakness are aggravating, in retrospect, as the movie unfolds, his psychological profile is rational. If he has a diagnosis, it is CPTSD. He is not crazy, and unlike Aster’s prior protagonists, he has more of an understanding of his powerlessness.

The biggest surprise of “Beau Is Afraid” is realizing that Beau is not dumb. If I ever find the temerity to rewatch the film, it will be to filter every scene with that fact in mind. To a certain degree, Beau knows that he is performing against his will, not living, enslaved with no benefit of a script or compensation for his performance. When I complain about the film’s length, I am uncertain what I would cut because flights of fancy such as the stop-motion sequence, a play within a play, a metadrama, mise en abyme, which Cristobal Leon and Joaquin Cocina directed, gives viewers an unmediated peek into the character’s soul, hopes and dreams without other characters overriding and dominating Beau.

In the outside world, Beau is the focus of surveillance cameras, not the hero, but the villain. Shakespeare’s famous line comes to mind,

“All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages.”

Beau never gets seven acts, but he survives and lives compared to his oneiric bathtub doppelganger. I wondered why random people were afraid of him-the cop, the guy hanging above his bathtub, or others who were so hostile and focused on him such as the super, the tattooed guy or Jeeves, but in retrospect those people’s actions make sense considering who he is in relation to the god of their world, the real director, his mother. The hostile group are allies, defenders tying him to the truth, slaying anyone and forcing him away from anything that lulls him into a false narrative of security, fantasy.

Movies have often been compared to Plato’s allegory of “The Cave” where people are chained, but see shadows on the wall, which represent but are not reality. Shadows play a pivotal atmospheric role in a childhood memory in which his mother (Zoe Lister-Jones) tells an unsuitable bedtime story of his conception and his father’s death to child Beau with a bedside zoetrope projecting different flashes of color on her face evoking the nightmare images of Dario Argento’s giallo films-purple, yellow, green, red. Some of those people believe that those shadows are reality, but the philosopher or higher mind, like Beau, recognizes it as an image, a lie. Beau’s imagination relives the aspiration of being a chain breaker. Beau’s will to live is the hope to live in a world without god, an independent existence filled with reality, not simulacra. The denouement includes Beau entering then emerging from a cave via a motorboat, but there is no reality, just another simulacrum so instead of futile exercises in going deeper just to uncover another matryoshka doll, he accepts a sentence of oblivion.

The role of water in the narrative is the catalyst for the action of “Beau is Afraid.” Beau, a man reluctant to make choices, embraces water by refusing to leave the bathtub, leaving his home to get water to take pills then chooses to explore the unknown and abandon civilization in a motorboat. Water is an ancient symbol for God and/or primeval chaos. For Beau, water is the impetus for all the big upheavals in his life such as discovering his first love either on a cruise or an oceanside vacation with a dead body in the pool. While his mother can try to shape his experience with water by influencing the form that it takes-through pipes, in bottles, the actual water does not change. While people can have ulterior motives and hidden agendas, water is immutable. Beau rarely refuses to do anything even if it is unreasonable, but refusing to drink blue paint, the opposite of water, is emblematic of his life. He plays along even to his detriment to a point, but he is anchored in his attraction to this element.

“Beau Is Afraid” is a surreal Boots (“Sorry to Bother You”) Riley-esque “The Fabelmans” (2022) meets “The Truman Show” (1998) without being derivative and still delivering quintessential Aster cinema from traumatic, fatal head injuries, abrupt time lapse edits, flashes of playful light. Aster is still detailed with diegetic sound invading a silent room, photographs and paintings decorating a room being significant, fraught meaning behind a microwave dinner. People cannot function without prescription medicine because having authentic feelings/normal reactions to trauma are forbidden. The acts vary in length and contain flights of fancy such as palette cleansing flashbacks to Beau’s childhood, dreams and memories. The first act is the tightest and funniest. The laughs get fewer and far in between as the film unfolds and becomes a punishing viewing experience that threatens to never end.

I have watched silent, black and white Polish films and hours of German artsy fartsy fare, and three hours was a bit much for even me. The trial denouement felt like a criticism of the audience viewing someone else’s pain as entertainment then milling out as if a tragedy did not happen. It feels as if Aster is judging us for watching him pour out his soul onscreen then moving on without missing a beat. I peg it as autobiographical and hope that he is ok. I’d prefer Aster to be happy than entertained. (To be fair, another critic thinks that Aster is having fun torturing his protagonist and us, which may be true.) I understand that it may be his reality, but as a viewer and a critic, I am rooting for him, not bored and indifferent. I agree with others who compare it to “Defending Your Life” (1991), but trials rarely work in movies however I appreciate that unlike the way that most filmmakers utilize the trope, it does not lead to a protagonist’s vindication, but is the final nail to his condemnation. I love a bleak movie, but I do not relate to this pain as I did in his prior films.

I prefer a woman protagonist and find Phoenix to be an excellent actor who is at his best when the director keeps a tight leash on him for the onscreen part of the performance. Aster and Phoenix made a tight pair, but I hope that he does not become his muse. Aster and Phoenix succeeded in making a movie with a domineering woman figure without triggering misogynistic alarm bells, a high bar for Phoenix to clear given his alleged history. Maybe the Jabba the Hut penis monster helps. Or the absurd orgasmic relief/literal petit mort towards the end. The film’s rejection of escape through another person dissolves expected gender roles. The cave did not feel symbolic of a vagina although it could be a symbol of thwarted rebirth.

I rate “Beau Is Afraid” higher than Noah Baumbach’s “White Noise” (2022) because regardless of how a viewer may feel about the movie, it is a cohesive, committed vision about a man’s interior life materialized in his surroundings. Others have already compared this film to Charlie Kaufman or Darren Aronofsky, which is a fair comparison, but Kaufman and Aronofsky’s flight of fancy can be annoying whereas Aster had my attention the entire time. My editor compared it to The Daniels “Swiss Army Man” (2016), which I still need to see. I agreed with comparisons to “A Serious Man” (2009) except unlike that Job-like protagonist, Beau never had anything to lose or had anything that he wanted to keep.