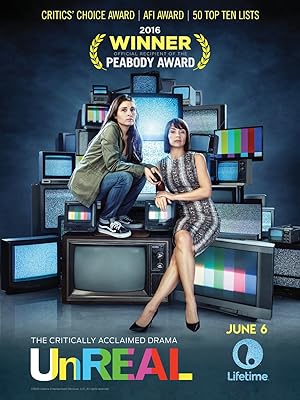

“UnReal” is a four season, thirty-eight-episode, series that focuses on Rachel (Shiri Appleby), a producer on Everlasting, a dating reality show reminiscent to “The Bachelor.” Rachel is torn between feeling guilt and pride in being a master manipulator to create salacious content for ratings. Her toxic work environment is a comparative refuge from her upbringing.

“UnReal” is a clever show. It attracts audiences with the promise of a cynical behind the scenes look at a reality show, which makes viewers feel like insiders and superior to fans of and participants within the genre. It gets us to stay by sucking us into the lives of the people who work behind the scenes, and we end up in a soap opera with over-the-top plot twists. If you watch this series and are thoughtful, you may walk away thinking of the morality of your own viewing habits and recognize your culpability as a viewer and someone who enjoys or at least consumes the manipulation. If the producers are moral monsters, but we empathize with them because they are human beings with hopes and dreams, hopefully it will help us question on our own morality for encouraging such content. By the fourth season, the contestants are savvier, and while less deft at manipulation—it is not working if you can see it, call it out and leverage their awareness for more benefits. Entertainment becomes human sacrifice, and the people behind the scenes are soul murderers.

“UnReal” is a perverse morality play that asks if there is any line that these producers will not cross for the sake of success? The answer is no, but just because they do, it does not mean there is not a deleterious effect on them. They do have a warped sense of reality, loyalty to each other and protecting each other and the show, but even that morality is fluid because they inevitability hurt each other. While it starts as a battle over the soul of Rachel, Quinn (Constance Zimmer), her boss, also plays a central role. This battle exhibits itself in two ways: as a mother off competition with Quinn versus Rachel’s biological mother, Dr. Olive Goldberg (Mimi Kuzyk) and a one-sided child off competition with Rachel becoming jealous of Quinn’s focus when it shifts from work to her personal life. Though Quinn is toxic, in this universe, she comes off better than expected.

Appleby does a phenomenal job playing Rachel. She reveals these flickers of real emotion to give us a glimpse of how Rachel feels whether a wry smile of triumph over doing something wicked or the pained expression of guilt and horror. She is an unstable character because of past trauma and abuse, but it is unclear if she also has a mental disability. During the first three seasons, I thought that she did not, but was responding in a human way to negative experiences, but by the fourth season, she did seem to be exhibiting signs of a mental disability though the show never lands on a diagnosis. To be fair, the fourth season felt as if it had jumped the shark and was doing an amped up reboot/retread of earlier storylines but was not without merit. The series had recycled and reframed storylines before, but it felt thematically cohesive within the season. The series battles over whether Rachel will stop torturing herself by manipulating.

Quinn is amoral and ruthless. She revels in torturing her contestants, but is brutally honest with herself and others in a way that felt refreshing. Unlike all the characters, she never repents and knows herself thus knows where to draw her line albeit it, it is not where the average person would. Like Rachel, she can be wounded when other people critique her, but it does not make Quinn change if it is not in line with her strong sense of identity whereas Rachel spins out. Her pivotal moment is when Rachel says, “You may want to be Chet but I don’t want to be you, Quinn” Quinn replies with a broad smile, “Yeah you do.” It does not matter if Quinn is right. Quinn is so confident and unbothered without missing a beat. Quinn may be a monster, but she can live with herself and her choices in a way that no one else can. Chet (Craig Bierko), Quinn’s colleague/boss and lover, is almost as mutable as Rachel. Most characters are trying to reinvent themselves and recalibrate to avoid hurt, but Quinn is a constant and whenever she gets close to self-destructive behavior or annihilating coping mechanisms, she stops short and faces the music. It makes her an unlikeable person that I ended up rooting for. I liked Zimmer when I first saw her in a way too brief role in “Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.,” but now I love her. I only had one problem with her storyline at the end of season 3. She beats her enemy, and instead of taking that person’s job, she gives it to someone else who was more vulnerable and betrayed her. It made no sense that she would not try to take that job herself.

Each season of Everlasting is supposed to reflect at least Rachel’s psychological state. The first season is the most straight forward as a battle over Rachel’s soul-career or happiness. It is traditional with a famous titled and rich British suitor, but the horror is still there as even he chooses to pimp himself out for success. The second season is a battle of the sexes behind the scenes, but becomes a challenge for Rachel to uphold her values by creating a storyline that results in authentic true love. The third season is Rachel trying to escape the show, choose healthy relationships and stop reenacting trauma. The fourth season goes full tilt in the opposite direction, and Rachel feels less like the main character of the series though she still is. It feels as if Quinn is, and Rachel is trying to do to Quinn and herself what she thought Quinn did to her.

I find horror movies comforting, but “UnReal” feels like more realistic horror with the social interactions. The threat of rape and realistic violence is omnipresent. I am uncertain if it suffers from hipster racism—when a liberal or progressive person does something racist but is conscious of it and calls it out, which does not negate the racism. The series treatment of Jay (Jeffrey Bowyer-Chapman), a gay black producer and other characters, feel as if it walks that fine line. On one hand, it is credible that other characters stereotype him as a possible source for drugs, but then it becomes his whole storyline. Sure there are plenty of characters that do the same thing, and he has the right to be as toxic as Rachel, but I still felt some sort of way about it. Madison (Genevieve Buechner) had a great story arc as a lesser foil to Rachel and Quinn. You could get whiplash following her. Bierko become Chet complete with crazy eyes.

While “UnReal” tries to tackle the problem of Americans losing themselves in their work, like most shows, that critique falls short by failing to provide a credible alternative or any successful relationships outside of work. Work becomes family, lover, and friends, but all-American shows are propaganda to trick us into sacrificing our lives to production. It is unhealthy to make work your sole fount for a social life.