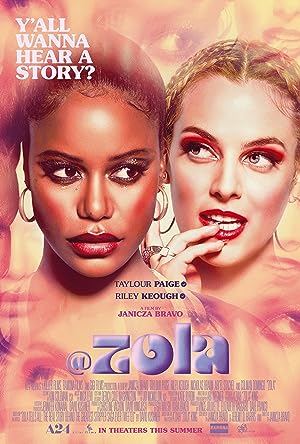

“Zola” (2021) is a film adaptation of Aziah King’s Twitter thread (@_zolarmoon) posted October 28, 2015, which I read soon after she tweeted it. At the time, the story was received as a hilarious adventure in the underworld of sex work with a street smart, unwilling participant who survives the wild weekend. Zola (Taylour Paige) meets Stefani (Riley Keough, Elvis’ granddaughter) while waitressing at her day job. The two hit it off when they discover that they love stripping. Stefani invites Zola on a road trip to Florida to strip, but things go downhill when Zola discovers that it is literally a hoe trip.

I wanted to see “Zola” while it was in theaters. I am unfamiliar with Janicza Bravo, a black woman director, who wrote and directed it, but I do have her first feature “Lemon” (2017) in my queue. I was familiar with the original source material. I love supporting black people behind and in front of the camera, but pandemic. The subject matter is just outside of my comfort zone, personally conservative, that it felt as if it was too much of a risk to see it and not enjoy it. It is one thing to theoretically support legalization of sex work and another to watch it on screen. Even watching it at home, I clutched my pearls over the profane prayer, and I left the movie puzzled. I did not enjoy it, but it bothered me. A movie that makes you feel is called art. Art elicits a strong response so after the initial shock wore off, I rewatched the film a couple of times twenty days later. It benefits from a rereading of the original thread, and reading David Kushner’s Rolling Stone article, “Zola Tells All: The Real Story Behind the Greatest Stripper Saga Ever Tweeted.”

“Zola” bothered me because it is billed as a comedy, but it is not funny, and I and everyone who laughed at the Twitter thread should have gotten it sooner. It is disturbing because it is about a black woman who could have become a victim of sex trafficking, but if authorities got involved, would the authorities arrest or rescue her? During the denouement, Zola asks, “Who’s looking out for me?” No one, not even herself because she did not see any of this coming. The most harrowing points of the film are when she is in danger, but still in communication with the people who love her, her mom and boyfriend, and have no idea that she is in jeopardy at that moment. There is only one person who notices when she is in trouble. Fifty-one minutes into the film, a pool attendant at a hotel intervenes but she and X, Abegunde Olawale (Colman Domingo), brush him off. Why did I not get that when I was reading it? Would people get it while watching it? I wanted Bravo to tell, not just show, although the best filmmakers do the opposite. It bothered me because maybe we found it funny because of respectability politics, and we had internalized misogynoir. We did not take the danger seriously because we were too distracted by the setting, the language and general flashiness that we confused it with being part of Zola’s world. It is one thing to intellectually understand, and another to recognize it when we see it. Of course, a stripper is not the same as a prostitute, but because the author does not spend time discussing the psychological impact in the same way that Paige does with her body language and facial expressions throughout the film, we forget that unspoken does not mean psychological issues are not present. I am still concerned that people won’t see Paige’s performance and get it. There is a casual background moment of police brutality to highlight the obtuseness and irrelevance of the law to protect people because they are missing the real crime. Also when Zola’s work ethic kicks in, and she becomes a better pimp than X, her professionalism in this context makes us forget about the danger. She turns the tables on Stefani and X briefly so we get confident that she is impervious.

“Zola” bothered me because I did not understand why the protagonist was initially enthusiastic about the trip then changed her mind early in the proceedings, 11 minutes into the movie, even though at this point in the film, nothing has changed. There is no danger, just boredom. Again I wanted Bravo to spell out Zola’s feelings because they were inscrutable. Bravo has too much faith in her viewers to discern her visual language of bright colors contrasted with adult realities. Bravo paints a world reminiscent of the adult version of Barbie dolls with women upholding beauty standards as a way to continue playing dress up. There is the crackle of little girl friendship intensity when they first meet that only gets recaptured during the road trip when Zola’s irrepressible work ethic kicks in after the unconsensual Backpage ad is posted. Zola is disinterested in conversing with men, and they are on the road trip. Her boyfriend is background scenery interrupting her fantasy, a fantasy that she can indulge with Stefani, but dies in the denouement. When Bravo introduces Zola working as a waitress, she is talking to a fellow waitress, Gail (Nelcie Souffrant), but is silently frustrated that Gail cannot bounce effortlessly between work and shop talk then leaves her with all the work. Also Zola’s passion is stripping, and Stefani presents as just as into the craft as Zola is. They work together and makes loads of money. Her fantasy of being the center of attention, changing her identity into someone she crafts that is not like her daytime self, a servant, but a star and finding someone who shares the same interest is game changing. Implicit in one blink and miss it scene is that stripping with a white girl is more lucrative. So when she finds herself in a car with a couple of dudes, after they sing and dance along to “Hannah Montana,” she returns to boredom and disappointment with the reality of life. It only gets worse afterwards.

Instead of being a star, Zola gets microaggressions. From the compliment, “You look like Whoopi Goldberg” to “I ordered a white chick,” “Zola” paints a postmodern version of Manet’s Olympia and her maid and the conflict of desire/attention. The white woman becomes the center of attention, and Zola becomes her unwilling assistant keeping the bedsheets fresh and welcoming Stefani’s gentlemen callers. In Zola’s internal fantasies, she is alone or shares the stage with Stefani, but by the traumatic end, her mind dissociates and brings up the image of a computer screensaver, asleep, numb from the threat of violence, and she can no longer see herself. It is not the first time that Bravo uses imagery to reflect her character’s dissociation. There are two occasions when no human voices can be heard, but the background noise is amplified while the scene is shot head on: when they arrive at the motel and when Zola looks out on a balcony and gets a gun. The soundtrack uses harp music that evokes the soundtrack of children’s shows once again to contrast the environment with the situation and her innocence.

Zola has no desire to be a prostitute, but there is the conflict that her joy in her beauty and comfort with her sexuality constantly takes hits during this trip until they enter oblivion. She is valued as less than Stefani. The violence at the end is not just the threat of rape. It is the echo of slavery amplified by two black men treating her like an object. Dion describes her “fat ass” and Stefani’s “pretty face.” Stefani is not valued and treated poorly, but there is an element of twisted consent. The customers do not notice Zola, or the men buy her tough act aided by her blackness, but she cannot fool other black men.

This betrayal extends to Stefani when “Zola” takes a brief detour to allow Stefani to direct her short version of this film from her point of view, based on an actual reddit thread. She sees Zola as a stereotype, body rolling, dressed in trash, and using trash bags instead of luggage with curlers in her hair. It is Zola who is the Jezebel. They were never friends. Zola was a mark. Stefani reveals that she is an appropriator, not an appreciator. Stefani sees the culture that she embraces as ghetto when black women behave as she does. The movie departs from reality in the way that it depicts Zola and Stefani. Their hair and general appearance are more natural.

“Zola” bothered me because I felt similar to when I was watching “District 9” (2009). Was this depiction of an African man xenophobic? In the real story, the pimp is African, but here he often code switches from an American accent to an African accent when X gets agitated. Even if it is not xenophobic, the message is that Africans or aliens are more savage than civilized appearances, and the accent is hiding his true nature. As in the story, the black men are the bad guys, the sex traffickers, but blackness has different meaning throughout the film. X perceives disrespect and lashes out whenever someone addresses him with American colloquialisms. Domingo is such a great actor, especially when he is playing men of ill repute, and the movie translated the real-life character’s brutality from actions to words in his dynamic with Derrek (Nicholas Braun), Stefani’s boyfriend. The funniest parts of the film are when Zola comments on X and his life, and the most terrifying parts are when he threatens her. Domingo grounds the film in the real gravity in the situation.

During repeat viewings of “Zola,” I recognized my discomfort as similar to when I saw “True Romance” (1993) in theaters. If Bravo decided to stick to American crime dramas, Bravo could surpass Tarantino. The denouement is a mix of concern for Zola being unable to get herself out of this mess but also exultation that as bad as Mr. X is, just by virtue of being unwillingly at his side, there is a relief that you do not have to face off against him since he has no boundaries or loyalty except money. His love and business life could be a thesis. Baybe (Sophie Hall) could have a spin off. When Baybe talks, listen. Bravo also has surreal, but organic Lynchian moments, especially the last hotel’s other guests and how they act. What is on television? I loved the found footage elements with the cell phone and surveillance camera in the liquor store.

If there was an unexpected twist, I did not expect that Zola’s real foil would be Derrek (Nicholas Braun) since he plays the fool in “Zola.” They both fell for Stefani, who put them and herself in danger. Derrek is dense, but sympathetic. In one hilarious scene where he entertains himself as a self-soothing technique still believing in dreams of making movies and money, Zola empathizes after replying without emotion as if he is an annoying child demanding attention. She had the similar dreams, but related to stripping. They are characters who accept friendship and love from the wrong person.

Other reviewers have discussed Bravo’s depiction of the customers. They are like a conveyer belt, interchangeable in the first sequence, more menacing in the second. If “Zola” is shocking, it is because there is more full frontal male nudity, not female. For me what is missing is Stefani’s work. It is routine for her, but to an outsider, it feels like a marathon. She appears unaffected and unfazed, but just as the Twitter story does not reflect how shaken the author is, but “Zola” allows Paige to show her character’s inner life, the film permits Keough to only give us a glimpse of her character’s emotion when she shows pride in her work and wants validation from X then deflates when he denies her request. Also Keough reveals annoyance when Derrek jeopardizes her reputation. Otherwise she has chilling moments when she sides with X against her best interest—Stockholm Syndrome or is she proud of her work and feels it is her only way to earn money? It is hard to tell when she is genuinely scared or being manipulative to get someone to do what she wants. Keough has been doing great ambiguous acting for awhile. I am fine with Keough’s inscrutability because her performance appears textured, not vacant. Stefani is an uncomfortable mixture of perp and victim.

“Zola” is not a movie that I would recommend because I find it unsettling, but it may be a better movie than I am prepared to admit in this moment in time. I wonder if in retrospect, years from now, it will stand out in ways that more palatable films of 2021 do not. Bravo has a distinct visual voice with a firm resolve to let us sink or swim in understanding her message.