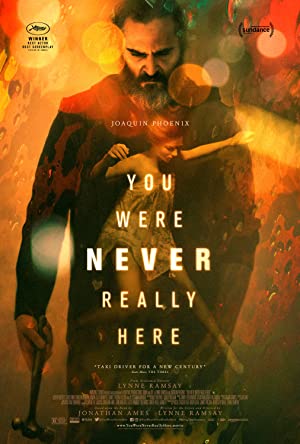

You Were Never Really Here is the latest cinematic feast offered by director Lynne Ramsay, who is best known for We Need to Talk About Kevin and may be one of the best living directors of our time. Joaquin Phoenix stars as a man who uses violence to avenge or rescue girls or women in danger, but this film is not a fun popcorn movie with an action hero. It is a visual portrait of a haunted, traumatized man using his work to process his past.

You Were Never Really Here is the kind of movie that I wish that I saw in theaters, but I don’t remember it being in theaters for long. Any Ramsay film should be seen on the big screen, but if you watch her films at home, no multitasking! Put your phone in another room and give the movie your complete attention. Ramsay’s films are the perfect example of showing and not telling. Even when the main character is an unreliable narrator, and events are not clearly delineated, the emotional texture and impact of every scene is clear and riveting. An added bonus is that this movie is only ninety minutes, which in the wrong hands can feel like an eternity, but wielded by Ramsay, is the perfect amount of time to gorgeously depict the raw and ravaged psychological landscape of the survivors of abuse suffering from PTSD.

Even though Phoenix is a superb actor, I’ve been repulsed by him since I’m Still Here when he managed to get the stank from Casey (rapey) Affleck, which Affleck has largely been able to dodge so I’m unlikely to pay to see any of his films in theaters even if it was directed by Ramsay, but I suspect that I’m only hurting myself. Phoenix seems to have inherited Jack Nicholson’s role as the go to actor for movies about characters who are heavily invested in getting justice for a wronged girl regardless of the level of actual personal connection (The Pledge and The Crossing Guard). You Were Never Really Here is Chinatown meets Taxi Driver with Phoenix outshining Robert DeNiro and Nicholson by balancing gentle caretaking and thoughtfulness with brutality.

You Were Never Really Here is magnificent in the way that even though Phoenix’s character is the main character, he occupies the edges of the entire film until we fully see him near the end of the film, and he finally becomes central to the story at the denouement. Ramsay gives us a man who is not even the star of his own life. He chooses to live in the margins preferring to be unseen out of a primal instinct to survive as he is psychologically frozen at the time of his earliest point of trauma as prey and to better stalk, hunt then kill his targets as the predator of predators. Violence is not glorified or triumphant, but fragmented, repeatedly assembled and disassembled to be more effective and elude detection.

You Were Never Really Here craftily counters his brutality by establishing his routine as a caretaker. I got a sense that left to his own devices, he would spontaneously combust, but through a life of service to others and putting himself in the backseat, it enables him to survive. By caring for others, victims and former victims, he gives himself the space to care for himself by being too busy to destroy himself. My favorite scene in the film is when we get to see him prepare his rental car for his next rescue. He is a concierge of consideration. Perhaps I imagined it, but I swear that his shopping bag included sanitary napkins, which is just next level thinking for a man to be so prepared.

You Were Never Really Here shows how he is aware that he is infected with toxic masculinity as he wields similar weapons as his father, but by directing that violence at acceptable targets in the service of those who need to be protected from that violence, he will not be required to eliminate himself. He may be an adult, but he is still the child inhabiting and rehabilitating his father’s body. The most shocking moment for me occurs in a stairwell during a brief, blink and miss it transaction that suddenly erupts into a rage-filled encounter.

You Were Never Really Here perfectly pairs the soundtrack with the visual and emotional tone of each scene. One notable example occurs in his kitchen as a 50s style song croons, “I’ve been undressed by kings. I’ve seen some things that a woman ain’t supposed to see. Do you know what paradise is? It is a fantasy we create about people and places as we’d like them to be.” In the theater, we may only subconsciously hear the actual words of this song and how it serves to heighten the tension of the overall narrative and the specific events unfolding at that moment, but the advantage of home viewing is to know with certainty what is being said or sung and knowing the devastating impact highlighting the tension between the characters. There are also atonal sounds to reflect the character’s internal chaos and a smooth synthetic sound that is reminiscent of a slick Michael Mann movie when it is focusing on Phoenix’s character as a smooth navigator of the underworld.

You Were Never Really Here subverts the conventional vengeance narrative by fully conflating the abused boy, now an adult man, and the girl that he is trying to rescue as he collapses into helplessness after an effective flurry of unseen, ninja violence, which psychologically does nothing to alleviate his pain. In a transcendent mixture of baptism and resurrection, he casts off his grave clothes or rends his clothing in mourning. His messy, realistic nudity is contrasted with the stylized, beautiful sexualized nudity in art. This movie is the consummate intersection of the glorification and innate beauty of the human experience coupled with the raw, ugly realistic underbelly of life. At this point, he becomes the one in need of saving. The editing and haunting imagery evoke the internal experience of living daily life and plunged into traumatic deep waters as if he was experiencing it at that moment. The problem with choosing professions that he subconsciously chose to save others from what he experienced is when it triggers that moment for him, and he is forced to take center stage, focus on himself and confront how he will deal with that pain.

While I think that You Were Never Really Here is a magnificent movie, I think that there is room for criticism that a man’s pain takes center stage, and a young girl’s pain must be placed aside to comfort him. It is similar to the same complaint that Sansa’s experience is more about Theon than her. It is problematic, but I didn’t mind it because in this movie, the main character was literally occupying the margins.

I loved You Were Never Really Here. Even though there is a lot of violence, it is not graphic. Even though sexual child abuse is implied, it is not depicted. Ramsay sticks to showing the effects of abuse, not the actual abuse so it never feels exploitive.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.