“Women Talking” (2022) is an adaptation of Miriam Toews’ novel, which was loosely based on an ongoing true crime story of a Bolivian Mennonite community. Starting in 2005, men and boys committed mass rape by using an aerosolized cow sedative to break into houses and drug the inhabitants until eight were caught in 2009, arrested and convicted in 2011, but the rapes continue, and while official accounts only list girls and women, the attacks may not have been restricted to a single gender, but males are not coming forward. If you are interested in learning more about the real-life story, watch Vice’s “Ghost Rapes of Bolivia” (2013).

“Women Talking” is set in an unknown location in the US in 2010 of an unknown religious community. The narrative is framed as a letter from Autje (Kate Hallett) to an unborn baby, the product of an unidentified rapist and serene, smiling Ona (Ronney Mara), who is described as similar to an earlier, offscreen excommunicated woman. After Autje and her sister, Neitje (Emily Mitchell), see a rapist, the religious leaders of the isolated community work on bailing out the rapists and demand that the women forgive the rapists in two days or will be condemned to hell, eternal damnation. The ticking clock advances when a rumor spreads that one of the men may return early. The letter provides an account of how the women decide to respond to this command. The women and girls of three families act as representatives of the entire community to vote: forgive, leave, or stay and fight for reform. The letter records how they decided, and how August (Ben Whishaw), the schoolteacher and a member of an excommunicated family who occasionally becomes the safe male scapegoat of their frustration and anger, took the minutes because the women in that community did not know how to read. So the letter indicates a happy ending, that the women find a place where they can learn and tell their stories without being ridiculed, shamed, silenced or punished.

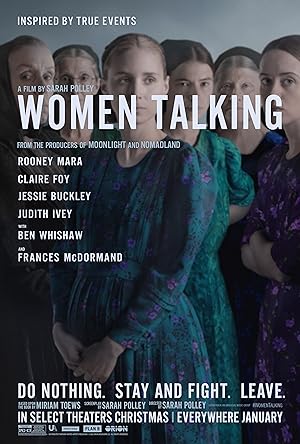

“Women Talking” features the following disclaimer, “What follows is an act of female imagination,” which is a way of reclaiming how these women’s complaints were dismissed. Actor Sarah Polley wrote and directed the film. Because I have not read the novel, I cannot differentiate whether Toews or Polley made a change to the original account. The film toggles between the past and the present with the narration of both giving a glimpse of the future. Even though it was not shot with black and white film, it appears as if it was. In the past scenes, boys and men’s faces are hidden. Because they do not treat the girls and women like human beings, they do not get that privilege on screen. Only the immediate aftermath of the rapes is shown, and the majority of the film concerns the deliberation, which becomes a philosophical placeholder soapbox for viewers to ponder larger societal ways that misogyny affects communities and how to respond to it evoking a gentler voiced “12 Angry Men” (1957). It is a play-like film meditation on power and how the power-hungry use His name in vain, but also on the unintentional violence that the women inflict upon each other through internalized misogyny when more quotidian abuse is known and forgiven.

There are two angry women: bitter from domestic violence and practical Mariche (Jessie Buckley), who lashes out at all who annoy her and mother of the narrator, and Salome (Claire Foy), who is frothing at the mouth for the opportunity to kill the rapists not from outrage on the violence inflicted on her, but on her four-year-old daughter. The decision-making process transforms into reconciliation among the women and a way to save their own souls. Leaving becomes the Christian response to violence-to prevent them from sinning and an act of faith, an unspoken continuation of the Biblical tradition of walking into the unknown with faith that God will provide a Promised Land free of violence and slavery, female versions of Abraham, Jacob, Isaac and Moses. Genuine forgiveness is impossible while the women are still vulnerable to violence, but possible with time and distance. It becomes a type of rapture with the women and children as the righteous leaving behind the unrepentant sinners.

For August, the other men and older teenage boys, the women and girls leaving is a threat of hell on Earth, exile in the soup of toxic masculinity without anyone to care for them. Staying becomes a celestial judgment of sin. August becomes one of the left behind who will try to save the remainder through instruction, but there are hints of his despair and depression at the prospect of being alone in this mission. Teenage boys under fifteen years must make a choice, a reverse Mark of the Beast. The women must confront the paradox of loving the enemy and having to protect themselves from violence when these boys do not choose them. Is an act of violence, a violation of free will, acceptable in this context? I do not think so even though I understand-a viper in the bosom.

It was a pleasant surprise to have a trans boy character and know that this new community would accept him and embrace this concept. If I had to complain about “Women Talking,” it was the devotion and time spent on the lost opportunity for love between August and Ona.

“Women Talking” is an aspirational film of the existence, though unseen, of a Promised Land for women, a simple, humble, practical utopia dedicated to Philippians 4:8, “Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable—if anything is excellent or praiseworthy—think about such things.”

Side note: It took me a long time to screw up the courage to see “Women Talking” because the real-life story is dreadful and who wants to spend their free time imagining such horror. After visiting a friend in hospice, I decided to see it because I could not get sadder and even a desolate distraction would be better than none. I have gone to the theater forever. There are signs above the theater. I knew what time it would start so when it did not start right away, I should have realized something went wrong, but I did not realize until long after the movie started in another theater and “Magic Mike’s Last Dance” (2023) started. Then I could not run out of the theater fast enough and went to the right theater long after it started. A couple of days later, I went again to patch up the viewing holes then left before it ended.

It was very difficult to think about “Women Talking” as a film without thinking of my many tertiary concerns surrounding the film especially erasing the place, time, identity of those affected in a fictionalized account. All movies are fictionalized even when they try to aim to be faithful. I also realized that an earlier version of my Jesus following self would have felt as if I was reinvigorated from going to church at this story, but now I could not suspend disbelief that leaving the community would be better and freer from harm than staying and fighting, but around two months later and a final at home viewing, I have come around to thinking this unrealistic hope is the film’s strength and is possible. There is a better place when leaving, always moving, never fighting. “Hope for the unknown us good. It is better than hatred of the familiar.”