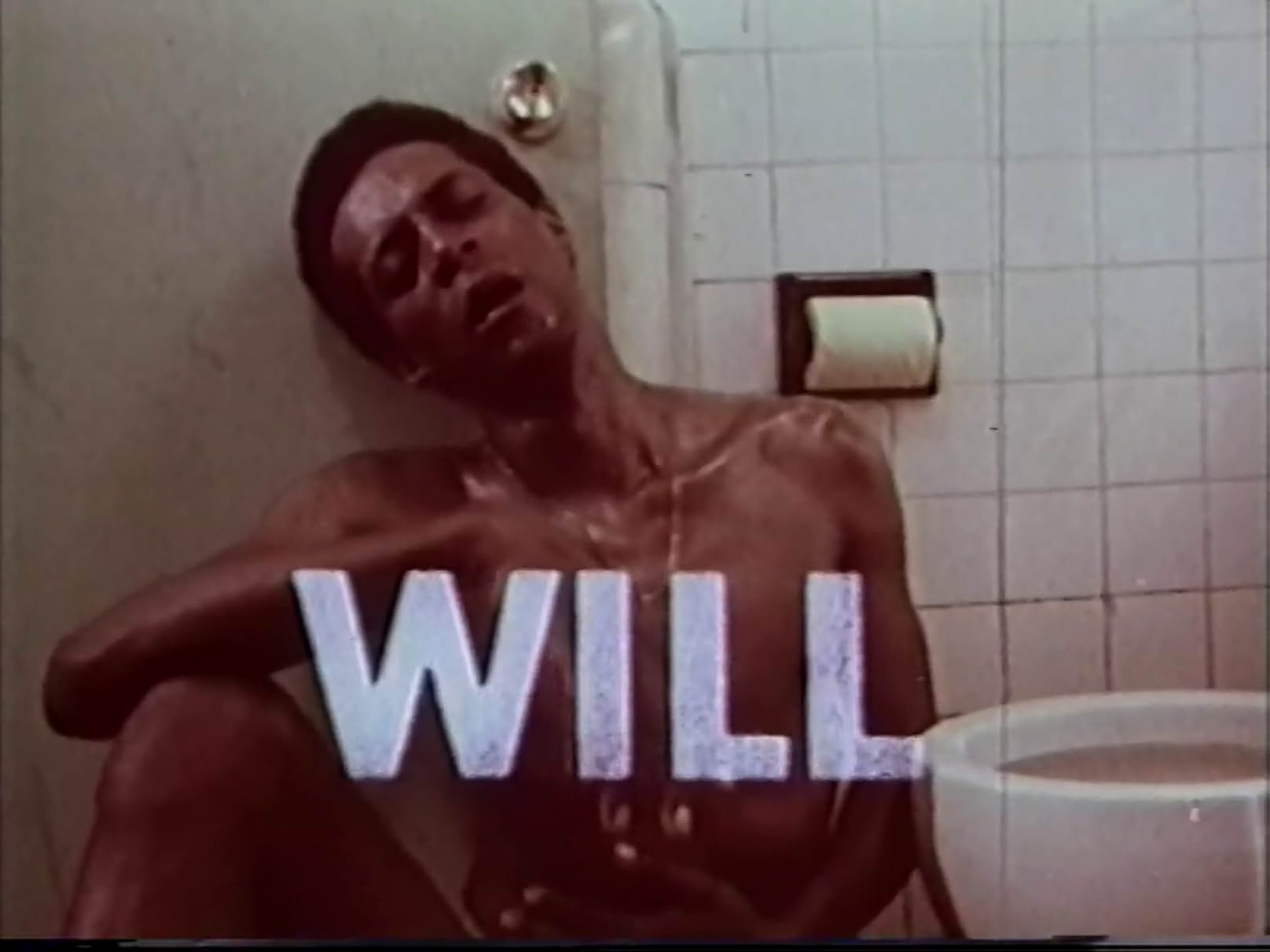

“Will” (1981) is about a man (Obaka Adedunyo) trying to find a way to kick his heroin habit and return to the straight and narrow. While purchasing his next hit, he meets Little Brother/Delbert (Robert Dean), a twelve-year-old child who is already using drugs. Will decides to help Little Brother; thus, having an incentive to do better, but Little Brother does not realize that his sudden good fortune is linked to being Will’s sober buddy. Will they choose a better life?

Thanks to funding from SI-NMAAHC Robert Frederick Smith Center for the Digitization and Curation of African American History, the Black Film Center & Archive and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture’s Time-based Media Archives & Conservation staff restored a 16 mm color print of “Will” that director and cowriter Jessie Maple donated to the BFCA in 2005. I definitely want to read her autobiography, “How to Become a Union Camerawoman” (1976), but it is out of print. The work was completed in 2020-2023. Even though I normally do not watch films about drug use, I made an exception because a Black woman made it, and it features Loretta Devine’s film debut as Will’s wife, Jean. If you are a Devine fan, then this movie is required viewing. All the performances are natural and perfect for that era. The film often feels like a combination of a play, a Sid Davis cautionary film with a secular, secret Jesus proselytizing mission devoted to positive thinking.

Depicting a story should not automatically be equated with cosigning what is being depicted, but the first third of “Will” is the hardest to get through because Will is simultaneously portrayed as awful but right even when wrong. Will takes his wife’s money explicitly announcing that he plans to buy drugs then chides her when she thinks that he did it. He does not have an affair because his body rebels, not because he loves his wife, and it is actually a funny scene because bodily fluids punish the ignorant sexual harasser and past flame, LaVern Hampton (Mimi Ayers), for her wantonness. Then his unemployed self brings a child home and tells his wife to kick the child out if she does not want an additional mouth to feed; thus, requiring her to feed three people, not just two, or be the automatic bad guy instead of the irresponsible man who does not consult his wife before making decisions even though he makes zero financial contributions to their shared life and makes her job harder. DTMFA! Because Adedunyo is an attractive man, the story validates his authority, especially the denouement when well-intentioned Jean interferes with his decisions on how to raise their de facto adopted child. “A Thousand and One” (2023) apparently was not so far off the mark in terms of just being able to grab kids and take them home with you as long as the kid is cool with it. Shout out for period accuracy.

“Will” is the kind of film that improves with repeat viewing to appreciate how Maple casually drops hints in the opening scene of the narrative’s trajectory. She introduces Will at his lowest point. Editor Willette Coleman intercuts flashbacks from Will’s glory days with his present circumstance then diegetic sounds portend the transformation in Will’s mind from the irritating static of addiction and withdrawal to a possible path to his redemption. It is easy to dismiss the scene as a simple establishing scene, but it is a terrific way to condense the entire story in a short sequence. Will’s redemption lies in basketball, and the program on the radio is not just a program that happens to be on but is motivating Will. It is Will’s first choice after having fevered visions of memories.

When Will decides to listen to the speaker, Bonaker (Elwoodson Williams), in person, the Chi Rho symbol hangs above the speaker’s head, a monogram that is shorthand for Christ. So even though the words are not explicitly Christian, it is Christian coded. Side note: as a Christian, I’m not a fan of toxic positivity, which should not be conflated as a requirement for following Christ. The Psalms and much of the Bible is devoted to things going wrong and staying wrong. The trick is to not falter as things go south whereas Will is rewarded for finally seeking higher ground. This higher ground is referenced in the earlier drug score scene, but it sounds like gibberish until the church scene. Then when he rescues Little Brother from drugs, he races him to a high point. It just seems like innocent horsing around and educational, but Maple never stops visually making the themes literal even if it seems organic and casual.

Maple devotes a long time to showing the sermon in its entirety and the girls’ basketball game. The twenty-first century makes it hard to sit through extended scenes, especially if you are a sports atheist or not into the message, but considering that the intercutting of past and present symbolized withdrawal, sustained attention can be equated with wellness, living in the moment and finding a higher ground instead of just being high, Also Maple is using her film to preach to the audience, disgust them with the grueling images of the effect of drug use (don’t eat while watching “Will”) and glamorize the clean life by showing Will immersed in art, sports and community. It is positive propaganda that I happen to agree with, but what would Dr. Carl Hart, a Columbia University neuroscientist and psychology professor, think of these images considering he uses heroin to unwind? (I’m so jealous because I just want to use ibuprofen without negative consequences.)

As a child of the Eighties, during the “Just Say No” campaigns, everyone had an idea that people would jump you and make you use drugs. Did the idea come from “Will?” Shot in Harlem, the film captures Manhattan before gentrification, in all its unique, gritty glory. Her portrait of individuals and landscapes are similar. She appreciates their beauty and is not blind to their worst flaws. Albeit offering simplistic, pat solutions to recovery, the film does not adhere to one-dimensional respectability politics or demonization. She chooses not to ignore, but center marginalized, flawed male figures whom many would write off. Unlike cautionary films, she chooses to end with a redemptive arc. When people are exposed to an excess of unremitting reality, imagining a happy ending is not a cop out. The utopia coexists with the dystopia. “On earth as it is in heaven” is in the same place.

“Will” is not a movie that I will revisit at home, but it is essential viewing for film history buffs, especially if they are interested in Black films or old school Harlem. Maple made a second film, “Twice as Nice” (1989), about twin sister basketball players, and I definitely want to check it out. Now where could it be?