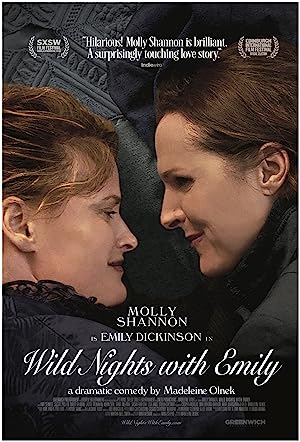

2019 seems to be the year of interrogating the costume period drama, specifically why do we think of the past in a hazy, romantic way when the people of those days probably thought and felt similar emotions to us. Wild Nights with Emily is a funny, postmodern examination of Emily Dickinson: the actual woman played by Molly Shannon, Mabel Todd’s public persona of Dickinson as artistic expression in the medium of promotion and the woman that her family and friends knew and loved.

Madeline Olnek, the director of Wild Nights with Emily, can be described as an American Taika Waititi except more ambitious in terms of narrative structure and less childlike, definitely more adult without being smutty or steamy. It is a light romp, a sex comedy. The film toggles between 1880 during Mabel’s publicity tour of Emily’s poems, 1860 to compare and contrast Mabel’s account of the author with the real woman and adolescent Emily and Susan.

While Ulnek humorously undermines Mabel’s authoritative stance on a woman that she never met, she simultaneously sympathizes with her. Wild Nights with Emily is also a portrait of three women, trying to live their best lives in the nineteenth century in a world dominated by silly, incompetent men, and in many ways, their happiness and posterity are intertwined though there was no cheesy woman solidarity between the three. Mabel, played by professional chameleon Amy Seimetz, may not be talented herself, but she has an eye for talent that none of her male contemporary counterparts had. Without her ability to understand and give the public what they want, the art of promotion, Emily may be lost to us. (I’m not into poetry so not such a great loss for me, but still!) It also doesn’t hurt that Mabel’s success is also an effective swipe at a legal rival standing in the way of her happiness-Mabel was having an affair with Susan’s husband.

Wild Nights with Emily never loses sight of the fact that the characters weren’t just dusty intellectuals mooning over words. They are passionate, silly creatures driven by love and sex, especially as they get older. It puts these women in conflict with one another because none of it is rational. In contrast to a movie like The Chaperone, there is no reasonable solution to their desires, but their desires put them into conflict and unexpected rivalry. Appearances matter in unexpected ways though it does not stop them from living fully with the one that she wants to be with. Sex is literally and emotionally awkward for everyone involved, which doesn’t only include those engaged in intercourse, but everyone nearby who has to avoid encountering reality.

Wild Nights with Emily is funny, but an early crucial mistake was including the young Emily and Susan. The tenor of the movie during that era is more conventional though it is depicting an unconventional romance. It ruins the otherwise dynamic film by making the narrative feel as if it is suddenly stopped in its tracks and too familiar, earnest, predictable as a young romance. The girls are too luminescent and boring. I would have preferred spending more time with the women than the girls.

Shannon and Susan Ziegler as the adult Susan have an onscreen chemistry and such individually different, expressive faces that if Wild Nights with Emily was a silent film, it would have still worked without the teen romance. Their eagerness to stop everything and be together as often as possible, which never cools with age, is as prolific and intimately intertwined with Emily’s writing, which is the central thesis of the movie.

Wild Nights with Emily is very similar in the lofty goals of The Big Short and Vice’s Adam McKay to use humor to depict something serious and academic that would normally drive viewers away if it was a documentary. This movie is actually an adaptation of a literary academic book by Martha Nell Smith, Rowing in Eden: Rereading Emily Dickinson (apologies if I got the reference wrong and please correct me). It is rooted in academic scholarship that could veer into a cross between an American Masters documentary mashed up with a Nova episode, but brought to life instead of remaining a stodgy theoretical debate. The movie’s bookends points to the veracity of this theory and does not have to fight an uphill battle as Smith does when people dismiss her work as a queer studies agenda. Tweak the phrase a little, and it sounds awfully familiar to “gay agenda.” I thought academia was supposed to be a bastion of liberal thought; however the only agenda seems to be heteronormativity and the willful continued erasure of gay people from scholarship and history.

Alas if my brief time with Google is accurate, it seems as if the academic scholarship about the discovery of Susan’s name in Dickinson’s work mirrors Wild Nights with Emily’s depiction of the poet’s interaction with men and her work. They are very authoritative about it without asking themselves if they fully see it instead of instinctually dismissing it. Shannon is perfect as the poet as she remains superficially polite, but if the men that she entertained in her parlor actually looked at her face, they would be devastated and perhaps indicted by her intelligence. It is so much easier to talk at someone and remain confident than interact with someone. It is shocking to think how Shannon may have been wasted all these years as an actor. She can simultaneously play two levels in a scene-what the person before her expects from a woman and who she actually is. She restrains herself just enough that the bubbling forth of her real thoughts projected on her face is the real humor. The joke is on them. The words may be flat, but the inflection of the delivery and body language is everything. Women are experts at the art of conversation. If quoted out of context, comments seem innocuous, but in context, can be devastating.

Wild Nights with Emily’s entire cast is superb. There is a delightful and laugh out loud hilarious scene between Jackie Monahan, who plays Emily’s sister, Lavina, and their brother, Austin, played by Kevin Seal, that threatens to hijack the entire movie. Brett Gelman as the confident, but under qualified Atlantic editor, Colonel Higginson humorously embodies the underlying reason for my horror whenever people say things like “Women have come so far” or “times aren’t as bad as they were before.” Um, yikes. They said that then, and they were that bad. Watch this movie soon after On the Basis of Sex and The Chaperone, and you may actually feel as if you’re standing still.

I enjoyed Wild Nights with Emily. If the perspicacious Olnek is given the same opportunities as McKay or Waititi, America could have a burgeoning great auteur. I can imagine people being dismissive of it because it is so funny and dynamic whereas they prefer their poetry to be more somber to take it seriously. I would not call it a must see film since in spite of its brief length, it felt longer because of the early missteps, but if you’re looking for something a little offbeat and aren’t turned off by depictions of lesbian relationships, I would give it a chance. Dickinson fans should go.