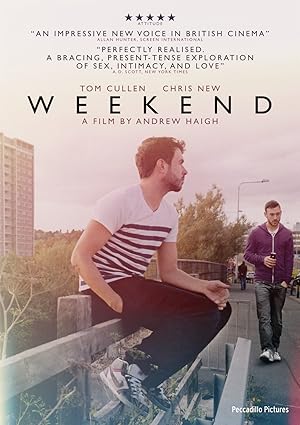

Weekend follows Russell who is unexpectedly shaken from his routine when he forms a mutual connection to a guy that he hooked up with. Both men are forced to confront the emotional veracity of their relationship and the way that they usually navigate the world. This film is more than a love story. It feels real as if I can find these characters in the real world. It is an authentic slice of life film at a crucial turning point in their lives that will forever change them regardless of what happens in their relationship.

I saw Weekend and Call Me By Your Name within a week of each other, and I can’t stop thinking about Weekend. In terms of composition, it reminded me of She’s Lost Control, but resulted in a completely different tone. I regret not seeing it in the theaters, but I did not even know that it existed. I’m not even sure how it ended up in my queue, but I’m delighted that it did.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Even though Weekend is only 97 minutes long, I felt like I knew Russell as a human being. I really liked and could relate to him. The way that the actor moved within his character’s apartment, and the way that the apartment was arranged felt like a real home. When we find out his backstory, it is in line with what we have seen about Russell. He takes pride in what he has accomplished. He has a job and a home. He knows who he is and learned how to survive probably without much guidance. He had divided his world into different segments, not fully engaged in either, as a safety precaution.

Weekend showed the hypocrisy of how even though homophobes may say, “I don’t care if you’re gay, just don’t flaunt it in my face,” heterosexual sexuality is omnipresent and a constant threat if he as a gay man does not at least permit it to go unchallenged. He may not be claiming to be straight, but he never replies, “No, I don’t want to _________ that girl.” His silence never comes across as a denial of who he is or self-hatred, but an act of self-defense. There is a thin, off camera or to the side of every shot threat of violence to gay men, a constant challenge to their existence. The iconic lovers saying farewell at a public transportation station is constantly interrupted by taunts. I wanted to jump into the scene and scream, “Can they have a minute! It is not about you! Shut up!” I think that the film wisely never depicts violence, but shows how there is a constant intrusion that alters every moment of a person’s life regardless of how open they are about themselves or if the moment is ordinary or monumental. He never feels welcomed even immediately after he wakes up.

I would classify myself as a cynical person, but I would also be a liar to say that I have not witnessed the beginning of relationships and instantly knew that a pair belonged together. It is rare, but love at first sight does happen. Weekend manages to depict that moment with Russell and Glen and sustain the mood that they belonged together. Even though a lot of Glen’s dialogue can initially seem off-putting or shocking (I’m thinking of his clapback shouted from an apartment window), it is a bravado that disguises a defense mechanism and is in denial that his life has fundamentally changed upon meeting Russell. He may not want a boyfriend or believe in relationships, but the lady doth protest too much. His actions reveal the opposite. How did you get here? Nobody’s supposed to be here! (Deborah Cox shout out)

Weekend works because you can feel how Russell and Glen interacting with each other actually make them better versions of themselves. Russell gradually erases his self-imposed emotional reticence because of how he feels about Glen. Glen abandons his performance and repeatedly reaches out to Russell. For me, the sign that it was a healthy relationship that encouraged growth as individuals and indicated that other than logistics, it could work in the long run, was when Russell was instantly a better friend to Glen than the ones who knew him for a longer time. He wants Glen to have a better life even if it means that he does not get what he wants. Glen’s literal surrender of his performance pose signals that he respects and understands Russell’s boundaries and by abandoning his distancing technique, he silently admits that Russell means more to him than a fun weekend. There are some authentic emotions and a potential for more if they can figure out how to make it work. Oregon needs lifeguards, right?

I loved the meta nature of Glen’s dialogue on confronting heteronormativity in his life and his work. Glen suggests that there is no similar guidebook for LGTBQ regarding how relationships are supposed to unfold. I am not a gay man, but I noticed that in films with homosexual protagonists, the couple rarely ends up together. Depending on the time period and location of the film, I can understand it, but it happens just often enough that I’m questioning whether or not it is a trope. I am probably annoying because when I discover that a person who belongs in the protagonist’s demographic has seen the film, I ask questions as if that person is now the spokesperson for all gay men even though I understand that there is not one uniform position. Gayness is not a monolith.

When I have asked some gay men about this aspect of the plot in romantic films with a gay male protagonist, they do not seem as troubled by this as I am. This acceptance was not in response to this film, but it is applicable here, “They have different lives.” The implication seems to be that it is better to have something transitory and perfect than refusing to let go when you find something extraordinary and finding a way to extend this happiness indefinitely. I just think that it is so rare to find someone that you can connect with on an unspoken level that the flames should be fanned. I don’t believe that heteronormativity is at play here since I also know a number of LGBTQ people who share my beliefs and live them better than I ever could, but it is an interesting narrative choice that I don’t fully comprehend, and I lack the objectivity to judge whether or not I’m trying to impose unrealistic heterosexual narrative norms that leave heterosexuals dissatisfied with reality to a homosexual dynamic that could be more realistic and gratifying in the way that it balances the demands of life with the desires of the heart, this is simply one story and not emblematic or if it is a trope rooted in bitter experience and oppression. I watch a lot of movies, but not enough with homosexual protagonists to have any satisfactory answers albeit even if I did, it would be a skosh arrogant as an outsider looking in.

I adored the spacing of characters and the composition of shots in Weekend. Russell is the central character, and the film visually reflects that. Even though Jamie is his best friend since childhood, and Russell is Jamie’s daughter’s godfather, we never get a good look at them. They are as much in the periphery as the straights that police and heckle him and other gay men. For once, heterosexuals can’t center themselves in the story. I did love that in a sea of meanness or casual cruelty, Jamie is eager to distinguish himself as a true friend even to the extent of temporarily not putting his child first. The underlying question in the film is if Russell fully shared his life, would he lose what he has, and the answer is no with caveats when applied to strangers.

I absolutely adored Weekend and highly recommend it. There are explicit sexual situations and drug use so if you’re sensitive to such content, run the other way. It is set in the United Kingdom, and everyone speaks English, but I turned on the subtitles because of the accents. Obviously homophobes need not apply.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.