Pedro Almodovar is one of the greatest living film directors, the rightful heir to Hitchcock’s throne with his mix of psychosexual driven dramas and an innovative storyteller who delivers uniquely crafted narratives. When Hulu notified me that his films were going to expire and be removed on June 20, 2017, I decided to watch all his films, including the ones that I already saw. This review is the twelfth in a summer series that reflect on his films and contains spoilers.

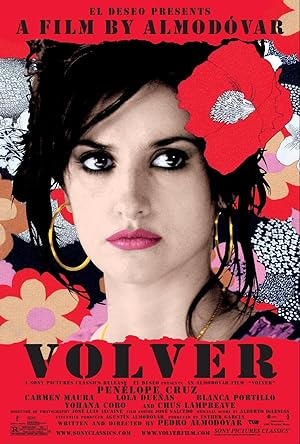

I saw Volver two times after my Hulu marathon. For an Almodovar film, Volver is fairly tame and could be broadcast on network television, but it loses none of its potency and could be his most poignant film to date, a beautiful depiction of wish fulfillment, getting a second chance at doing things the right way. There is only one implied sexual situation and only the aftermath of violence, but nothing sensational is depicted. The movie pays homage to the strength of women and the people behind the scenes who support filmmakers or in Almodovar’s life, nurtured and created filmmakers. Almodovar respectfully crafts a tale where these unsung performers modestly take center stage. Even though the film unfolds in Spain, Penelope Cruz’s performance and buxom appearance reminded me of Sophia Loren’s performance in Two Women except utterly more optimistic and heartwarming.

Volver is Almodovar’s take on the supernatural thriller, specifically an expansion of one scene from M. Night Shylaman’s The Sixth Sense when the mother played by Toni Collette weeps when her troubled son finally reveals that he sees dead people and relays a message of love to her from his maternal grandmother/her mother. Volver is a comedic ghost story set in the real world without the scares. Usually a viewer has to ask during the opening of an Almodovar film if it is real or not. Instead, for this film, he replaces this central question with how can this be happening? Because movies are a form of entertainment in which it is equally plausible to explain the impossible by using supernatural or rational theories, Almodovar uses our uncertainty to create a delightful tension that does not conclusively get released until the end of the film. I loved the idea of an Almodovar ghost story in which the ghost demands a makeover immediately.

Volver is a comforting world where the dead and the living coexist daily through the custom of tending to the graves of deceased loved ones or your own, working next to a dead body until you get some free time to discard it or letting the dead comfort and help you when you are at a turning point or preparing for death yourself. Almodovar’s image of death is not one of horror, but practical, warm and unifying. Death simplifies any conflict, opens any schedule, eases any burden and focuses the mind.

Volver is also a crime drama, including a murder mystery, a missing person cold case and a case for the Special Victims Unit without the involvement of law enforcement investigators. It felt like a second draft of What Have I Done To Deserve This and a happier alternative to Julieta. It definitely is a development of a storyline that initially and briefly appears in The Flower of My Secret. This film is a world where women take care of business, legal or not, even if homicide is justified, and the murderer could be exonerated. Their stories are private, not entertainment or a public matter.

There is a moment in Volver, reminiscent of the TV interview in Talk to Her, when the host tries to get the interviewee to spill the beans or die, and she chooses death. Almodovar believes that movies are more intimate and soulful than television, which he deems sickening, intrusive and crass, a vampire like the wealthy man in Broken Embraces. Even though the country town is described by all the characters as crazy, the real madmen are the people of Madrid, specifically the television host who describes herself as the friend of a dying woman while simultaneously refusing to offer medical treatment if the terminal woman does not sell herself for the amusements of others. Like Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, the only sane thing to do is to be crazy.

The narrative structure is linear, and people tell stories to each other to reveal the past and become closer to each other once the receiver is ready to hear the truth. The idea of justice is to accept the burden of what remains after a loss: taking responsibility of the disposal of a dead body for a violation of innocence, caring for the survivor of your victim, living in exile from the land of the living. Justice is light-hearted and communal in Volver. The scene in the hardware store reminded me of the one in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! except this shop owner betrays his suspicion with a rapid second glance.

I do not think that there are any LGTBQ people in Volver. Gender is binary. Women are vibrant, resourceful and knowledgeable. They deal with all the big and little things of life. There are numerous moments where women are moving insanely heavy, unwieldy and big items instead of asking men for help. Men are literally relegated to the sidelines, temporarily useful, leaving, useless or silent and unresponsive when a woman suddenly appears in his midst.

As Almodovar gets older, his characters become more staid. The only drugs used are medicinal and used to survive, to make eating feasible. The only alcohol is used sparingly during a celebration or to give a dash of liquid courage. The only one having consensual sex is doing it to financially survive because she is not a documented immigrant. (Where is she from?) The only refreshment needed is returning to your home village for spiritual and physical sustenance.

Even though the living’s daily life is dominated by the dead, there is a thrilling element of having a second chance to do everything right the second time around before death. The younger Paula does what Raimunda never imagined that she could do: kill her attempted rapist before he could destroy her life; thus freeing Raimunda from the drudgery of supporting her husband. She gets to be the kind of mother that she always wanted to have: an unconditional protector. As a result, Raimunda gets to fulfill two dreams: to operate her own business and sing publicly. Because she is able to heal these deep wounds, she is open to reconciling with her mother, who also gets a second chance to be a better mother. When she sees her mother, she leaves full of emotion, but unlike the first time, she has someone who can urge her to turn around and seize the opportunity for reconciliation. “I have to talk to her.” “Why don’t we go back?” “Now?” “Sure.” It is as if it never occurred to Raimunda that returning is an option, but once it does, she urgently rushes back as if she is running out of time, or her mother will no longer be there.

It is no accident that a film about healing and reconciliation features Carmen Maura, who has not worked with Almodovar since Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and sadly has not worked with him again after Volver. The most delightful part of being an Almodovar fan is the opportunity to see the ways that his actors change and stay the same. Maura still has that mischievous, expressive and playful face. I would be hard pressed to think of another older actor who could run around and hide without seeming ridiculous.

Almodovar does not just hark back to his past to add texture to his film, but references Hitchcock in the scenes that involve discovering and dealing with the quotidian complications of a dead body. He even uses a dash of Roman Polanski for a plot revelation that I expected early in the movie. He takes the most depressing elements of the story and somehow makes them invigorating and joyful for the viewer to watch. Ridley Scott needs to give Almodovar a call.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.