Trumbo is about Dalton Trumbo, a Hollywood screenwriter whose professional and personal life are disrupted after the House Committee on Un-American Activities subpoened him, and he was jailed for contempt after he refused to testify. He is unable to find work afterwards so the biographical drama covers how he was able to support his family until the political pendulum at Hollywood studios swung back in his favor. The film covers his life from 1947 through 1961 and is an adaptation of a biography by Bruce Alexander Cook titled Dalton Trumbo, but I have no idea if the book covers his entire life from December 9, 1905 through September 10, 1976.

Trumbo is appealing on many levels. It has a dishy, gossipy side if you are familiar with classic Hollywood and all the people involved in this story. It provides a grand civics lesson about how the timeless, theoretical US Constitutional values are brushed aside for the political concerns of our times. It also suggests something fickle about private business, and how the objective substance of that product, in this case a talented screenwriter, can never change, but the reception and popularity of that product is fickle and based on subjective feelings, not actual results like profits. The market isn’t rational and not based on money despite all claims to the contrary.

Trumbo alludes to, but does not reflect on how these norms are affected by gender. This movie takes great pains to convey the spirit of its titular character’s famous summary of this period, “It will do no good to search for villains or heroes or saints or devils because there were none; there were only victims.” The only person who could be called a villain in this movie is Hedda Hopper who is played by Helen Mirren and is the most nuanced character in the film. She is the antagonist for Trumbo, someone who uses her writing and popularity to destroy lives instead of creating them by producing jobs or stories except by centering herself as the arbiter of taste and political morals. Without controversy, she is no one since the story implies that she was exiled from accessing any professional standing for being a woman, aging, lack of sexual availability and as a victim of workplace sexual harassment. A blacklist already existed, but she performs a kind of judo that makes that negative energy work in her favor. She weaponizes and makes the private into something fit for public consumption. Trumbo is presumably collateral damage, but the movie does not explore if the people blacklisted were also somewhat culpable in her unofficial blacklisting by, at best, showing no concern about exploitation of women’s labor or at worst, actively participating in sexual exploitation of women at work. Her real target is the studio heads, who were explicitly condemned in the movie in a show stopping speech. It is incredibly rich that this incidental, #metoo storyline which serves to humanize the villain stands alongside a performance by Louis C.K., who plays an amalgamation of various historical figures, a man now known for sexual harassing women colleagues at the workplace.

Diane Lane’s streak of playing long suffering wives to famous, embattled men did not start with Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House. In Trumbo, she plays the titular character’s wife, and she does get enough lines to suggest that she had a life before her husband and will have a life after him if he does not play his cards right. Trumbo addresses a common theme that I’ve noticed lately in films about actual historical male writers including Goodbye Christopher Robin and Rebel In The Rye: how the entire household revolves around him. Trumbo’s wife and eldest child, his daughter, played by Elle Fanning, confront this presumption. Hopefully it also happened in real life because someone can be politically anti-establishment, but not confront that dynamic in his or her personal life.

Trumbo has a single black character that appears when the titular character goes to prison. The events of this scene occur after 1950, long before Stephen King would write Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, and shortly before the events of the fictional story, but this scene was filmed long after Frank Darabont adapted King’s story for film. I call it the “I Am Not Your Magical Negro” scene, and “this is real life, not The Shawshank Redemption.” It could also be called, “I am not the one,” and if you don’t know what that means, go to Urban Dictionary for a definition. One could argue that the movie counters one trope with another, the intimidating black man, but I will personally sign a waiver because the movie once again highlighted the inadequacies of Trumbo’s vision for the world by revealing another blindspot, racism, specifically his assumptions about a big black man in prison.

Trumbo never achieves a recognizable rhythm in its narrative. It feels like a television movie by what it chooses to focus on and depict as if it had a checklist of notable moments instead of a life being lived. Initially it appears that the film was going to set itself apart from its small screen leanings by visually depicting a scene being filmed in black and white, but this approach is quickly abandoned, which means that perhaps the film never should have done it in the first place because then it sets up unfulfilled expectations. Trumbo’s cast distinguishes it from a television movie.

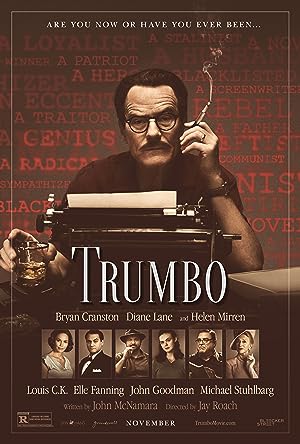

While I agree that Bryan Cranston is a solid actor, I first saw him in Malcolm in the Middle so I will always need a moment before I can stop seeing him as Hal. I have had a crush on Michael Stuhlbarg, who plays Edward G. Robinson, since Boardwalk Empire so I was delighted that he appeared in Trumbo, but John Goodman steals the movie from Cranston and Stuhlbarg in one scene that had more life in it than the entire film. For those averse to profanity, you should probably skip Trumbo, but profanity is used to underscore the character’s sudden forcefulness and gaining the upper hand in the film. When an American trade union leader, played by the perfectly cast Veep alum, Dan Bakkedahl, threatens Goodman’s character, Frank King, a founder of a film production company, if he does not fire Trumbo. Goodman shifts the tone of the scene repeatedly which makes his show stopping speech so great albeit worthy of pearl clutching, “Wanna keep me from hiring union? I’ll go downtown, hire a bunch of winos and hookers. It doesn’t matter. I make garbage! You wanna call me a pinko in the papers? Do it! None of the people that go to my fucking movies can read! I’m in this for the money and the pussy and they’re both falling off the trees! Take it away from me. I won’t sue you, but this will be the last fucking thing you see before I beat you to death with it.” Where is Kap’s King? I wonder how it feels like to own your own business, be insanely wealthy, but still get pushed around as if you are that person’s employee.

Trumbo reportedly has tons of historical inaccuracies, particularly in the oversimplification of communism during that period, but you shouldn’t be getting your history from movies. Movies, at best, are empathy machines, a type of secular church to teach you what it feels like to walk in another man’s shoes and sympathize with someone different from you. Based on that criteria, I highly recommend this film.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.