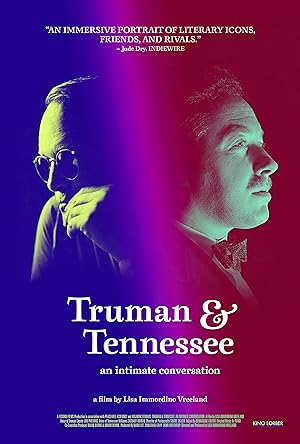

“Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation” (2020) is Lisa Immordino Vreeland’s latest documentary, but also her weakest after such successes from her directorial debut, “Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel” (2011), to her best “Love, Cecil” (2017). She decides to tackle two titans of literature: In Cold Blood’s Truman Capote (Jim Parsons) and A Streetcar Named Desire’s Tennessee Williams (Zachary Quinto). Capote and Williams were writers and friends so there is a plethora of material for the biographical documentarian to use when depicting intellectual icons.

Vreeland is at her best when she has less source material and must think creatively about how to make static objects appear dynamic. She does not use omniscient narrators, just the words of her subjects for the script. Considering Capote and Williams are two of the great American writers, this approach is wise. To illustrate words, Vreeland is usually phenomenal at finding ways to breathe life into the inanimate. Stay for the closing credits to get a glimpse of Vreeland’s editorial aesthetic. “Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation” uses archival footage from talk shows, home videos, clips from film adaptations of their written work and montages from photographs and newspaper clippings to animate their friendship for the big screen. Unfortunately because the majority of the documentary consists of clips from other directors’ work, it robs Vreeland of an opportunity to use her own signature style of using film as a personal moving scrapbook of her subject’s personal objects and publications, which gives the vibe of a private peek into the inner life of the famous as if peering into their diary. So watching this documentary feels like watching a clip show albeit a very elevated one, and I find that clip shows make me mentally wander instead of focusing my attention.

While Parsons and Quinto are good voice actors, I always think that it is a mistake for a documentarian to use a voiceover when the voice of the actual subject will be used in the same film, especially if that voice is distinctive. Then the voice actor needs to be a mimic or a generic traditional voice actor. Capote has such a peculiar vocal style that Houstonian Parsons is always going to lose if a comparison is inevitable. Toby Jones in “Infamous” (2006) came close in terms of physicality and vocal range, but Philip Seymour Hoffman in “Capote” (2005) is the definitive high-pitched voice. While Williams’ voice is less memorable, “Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation” gives viewers an opportunity to get familiar with it, which leaves Pittsburghian Quinto in the dust with his generic Southern rendition. Williams’ voice has a heavy, wet quality and watching him makes you realize that his tongue acts almost independently from the rest of his body so he struggles to pull it back as opposed to the usual drawl. The lisp is slight and coy. Parsons and Quinto did fine and are famous enough to draw an audience of viewers with no interest in the titular authors, but if Hoffman has an agent in the great beyond, contacting that person should be a priority for future Capote film biographers.

“Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation” is thematic and only roughly chronological, which means that after a viewer finishes the documentary, the viewer may only walk away with an impression of the two men’s lives, not a comprehensive profile. With an eighty-six-minute run time devoted to two figures whom any filmmaker could easily devote an entire film to each individually, the friendship angle, though insightful, feels like a premise, not the purpose. If there is an intimate conversation, it is between each author and David Frost, who is featured prominently in the film and guides us to compare the authors by asking them similar questions and seeing their different responses. If the documentary had analyzed Frost’s ability to catch famous people off guard, it would have felt appropriate. A chronological narrative has an innate momentum and trajectory that a thematic approach does not unless a filmmaker is trying to convey a conclusion to their audience about the subjects.

“Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation” does give viewers an idea of what it was like to be an author during their time, especially as gay Southern men who found refuge in art and Manhattan then found themselves sandwiched in between theater and film to popularize their work. There should be a disclaimer at the beginning of the film to viewers who want to be authors, “Warning: your life will not be as glamorous and wealthy as theirs.” There is a tension between the work and enjoying the fruits of this work through fame. As they get more famous, their work risks cannibalizing their life, which was always what was happening, but instead of obscure figures from their childhood without a public stage to air their grievances over their fictional doppelgängers, the person getting the fictional treatment has access to the same material, skill and public. There is an implicit threat of reprisal, which raises the stakes in this friendship. I never thought of Capote and Williams as contemporaries, just part of a vague past, but they were closer to us than the black and white film and photographs make us believe.

If there is a lesson in “Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation,” it is that writing and friendship can only do so much for an active mind, and the more voracious the intellect, the more self-medicating one may need. Also while writing provides an escape from the harsh world, it is still a temporary one. Somewhere in this documentary is a story about privilege and persecution. While these particular gay men were persecuted because of misogyny for failing to adhere to gender norms, their (race), gender and sexual orientation also formed a route to escape that persecution and have objective success in a way that other superb writers from persecuted groups could not. This topic exceeds the scope of this documentary, but would be a great jumping off point for another filmmaker.

On a more optimistic note, “Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation” also seems to conclude that while romantic love is nice, it does not endure like friendship if Capote and Williams’ friendship and lives are definitive representations. Vreeland seems to suggest that they were fraternal soulmates even if they never called each other that. They were competitive, cutting, teasing, and loving. They endured.

If you are a fan of either of the authors or the film adaptations of their work, I would highly recommend “Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation,” but if you are a Vreeland fan, lower your expectations because this documentary is no “Love, Cecil.” I still need to check out “Peggy Guggenheim: Art Addict” (2015).