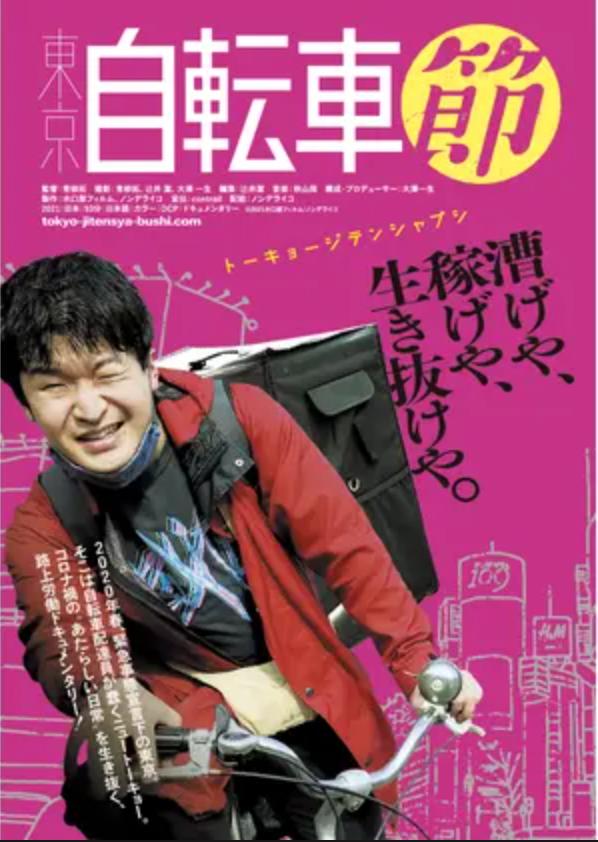

“Tokyo Uber Blues” (2021) [original title Tôkyô jitensha-bushi] is a performative documentary that focuses on director Taku Aoyagi, a recent film school grad, as he leaves home in Kofu City and bikes to Tokyo to get work as an Uber Eats delivery person at the beginning of the pandemic on April 21, 2020. Relying on the kindness of friends and the consistent demand for takeout, he hopes to be able to survive and pay off his student loans. Will his modest dream come true?

So there are two versions of “Tokyo Uber Blues”: the feature length version, which is 83 minutes long, and the television version, which is fifty-minutes long and will be showcased as an episode on “POV,” a PBS television series that broadcasts independent nonfiction films, which will air on October 21, 2024. If you have a choice between the two, the latter is probably your best bet. This review is based on the prior. Aoyagi is an affable everyman who presents himself as loving his grandma, coming from a close family and a hard-working, physically fit young man willing to go to extreme lengths to make a buck. His story is supposed to be emblematic of all the Uber Eats bikers looking for gold.

Aoyagi’s shooting and editing style are dynamic. Smartphones or GoPros mounted on his bike produce the effect of making the viewer see things through his eyes. Screencasting of texts with memes function as reminders of how mentally young Aoyagi is. Playing videos also serves to have talking heads discuss his plight without having the pull to get a one-on-one interview with the likes of Ken Loach, who predicted the Uberization of labor. Other videos reflect the progress of the pandemic and act as markers in time. It also depicts the process of becoming an Uber delivery person, the unmistakable, international chime of a new customer. A split screen shows his reaction to getting a job. Instead of narration, “Tokyo Uber Blues” periodically projects the tally of how long he bikes, how many deliveries he made and the money that he earned with all his effort. Before he accounts for business expenses like screen maintenance and tire repair, it is a lot of hard work with little reward.

At first, Aoyagi is not alone. Tsuchi, Kano a film school friend, is willing to lodge him until it is implied that the risk of getting Covid makes him withdraw his hospitality, A couple of high school friends, virtual fitness instructor Kazuki Iimoro and Yo pick up the slack for a while. “Tokyo Uber Blues” can be frustrating because Aoyagi is understandably so focused on his plight that he never shows whether he asked two of his three friends how they are able to survive without going outside and working. Is it commitment to the bit, considered impolite or a lack of curiosity? Yu reveals why he quit his job—a shady employer, but they all marvel at how decent the employer was to warn Yu before he got in too deep. The bar is in hell.

Unlike reality television, “Tokyo Uber Blues” is decorous and omits the moment when Aoyagi’s hosts withdraw their hospitality. Like anyone on a diet, which is basically what budgeting with no hope of earning a livable income is, Aoyagi starts to splurge on economical hotel rooms and the amenities that come with it but gets snagged with hidden fees in the fine print. He is understandably exhausted from biking all day so he starts to take days off, which means no income is coming in. He starts to lose money and never verbalizes why he does not return home. The problem with a filmmaker being the subject is the inability to create distance and tell a more comprehensive story, but to rely on viewers’ empathy and their ability to be so absorbed in the subject’s plight that they do not interrogate and want more from the creator.

“Tokyo Uber Blues” does effectively convey that the omnipresent broadcasts of safety PSAs and the reality of daily necessity are incompatible and contradictory. In the US, Americans who turned their attention to other countries’ effectiveness at following quarantine and low Covid deaths will be surprised at how the social safety net seems nonexistent in this documentary. Aoyagi’s grandmother makes a mask. Tsuchi, who is terrified of getting the virus, never wears a mask, but is strict about handwashing. A trip to the social security office shows the office workers masked, but the people seeking services wearing them below their nose if that.

Eventually Aoyagi becomes a part of the homeless community. Unlike the US, he is not in physical danger and never loses his expensive equipment when he starts to live on the street. An actor, Kenichin, offers tips on cheap places to eat and stay. Like the US, homelessness is not permitted. As Aoyagi enters Tokyo, his camera captures a glimpse of a Tokyo 2020 Olympics banner then later Kienichin explains that the homeless got shipped out of town to create the illusion of Tokyo’s prosperity on the international stage. Like Americans, Aoyagi starts to think that if he works harder or follows the advice in a self-help book, he will do better. Spoiler alert: he does not. It is unfortunate when a systemic problem becomes seen as a personal failing, especially if that person is one of a mass of victims.

“Tokyo Uber Blues” loses momentum as it approaches the end. Aoyagi starts using pandemic word association like beat poetry over visuals of his workday While it is an effective way to reflect the monotony and drudgery of an average work day, it is not a good way to keep people watching. It is also fiction because this documentary exists so it feels like a missed opportunity when Aoyagi fails to include how he has enough privilege to leave that life and make a film. It makes everything that preceded seem suspect and constructed, but Aoyagi is depicting an international, relatable common way of life. A skosh more transparency would not hurt, but help. Considering that Aoyagi is a first-time feature director, it is fine that he did not stick the landing, and the televised version will probably fix this problem.

Without spoiling anything, Aoyagi does get points for being incredibly vulnerable regarding the role of women in his life. “Tokyo Uber Blues” never shows women in a similar predicament because they rarely cross his path. As Aoyagi gets deeper into Tokyo hustle culture, he has fewer social interactions with people that he has preexisting relationships with. The exception: a woman whom he knows from high school, who meets him in a public place and gives a bag of supplies. He waxes starry eyed long after the brief encounter ends. All his interactions are not so wholesome, but basically good-natured as he wants to give all the money to the women who are not a part of his life in any capacity and those who are closest to him.

“Tokyo Uber Blues” is the rare Japanese film that references World War II in a critical way as a waste and idiotic according to an older woman who strikes up a conversation with the filmmaker. Aoyagi strains to make an analogy with the war on the virus and World War II as having the same devastating effect on its citizens, but it is apples and oranges. While retrospectively excessive, especially considering the impact on civilians, the Allies response to Japan may be harsh, it was an act of self-defense against unchecked cruelty over an entire region. In contrast, the response to Covid was an organic result of exacerbated, existing socioeconomic ills that like the virus, will never go away without a thoughtful, international, i.e. collective domestic, change of course.