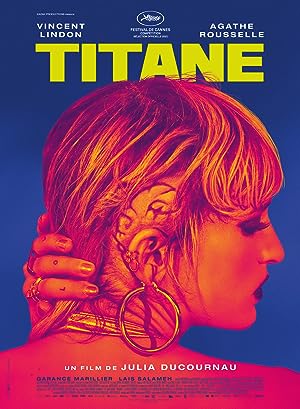

Julia Ducournau’s second film “Titane” (2021) is David Cronenberg’s “Crash” (1996) meets “The Imposter” (2012) with a healthy dash of “Demon Seed” (1977) and “Christine” (1983) except less rapey, more enthusiastic consent and no lines for the machine. Alexia (Agathe Rousselle in her film debut) was strange long before she had a head injury, which only amplified her aggressive interactions with people and her adoration of cars. When her actions begin to catch up with her, she decides to find refuge by taking advantage of someone’s grief, but finally makes a human connection to Vincent (Vincent Lindon), a delusional fire chief who paternalistically loves and supports her.

While “Titane” feels less cohesive than Ducournau’s directorial debut “Raw” (2017), there is a logical framework holding up the disparate elements of the film even if a viewer cannot discern them except in retrospect. The film feels so surreal that somewhere Cronenberg is kicking himself for not taking his sexual fetish themes to their natural conclusions. Ducournau and her cast are fearless in their approach to the subject matter. Alexia has a sexual attraction, a paraphilia, to metal but specifically vehicles, so she is a mechanophiliac, a ferrosexual, an objectophiliac. Before you run screaming, Ducournau does an effective job making a visual case for taking this sexual attraction seriously by relying on popular images of hot girls, cars and flames painted on the side of cars. The combustion engine links the fire fighter with the protagonist.

“Titane” is a Freudian and complements “Petite Maman” (2021) in the opening parent child car ride scene. The foundational relationship that defines Alexia is her relationship with her biological dad. The lack of paternal warmth explains her deviant behavior. She suffers from neglect. She only has a physical and psychological connection to the car, and only engages with her father through physically hostile behavior. He is annoyed and repulsed whenever he is forced to have contact with her. Instead of this revulsion creating self-loathing, she normalizes aggression when she needs human physical contact. When Ducournau introduces the adult Alexia, Alexia only has terse, token human interactions otherwise she ignores people as irrelevant unless they have a piercing, then she gets interested. As an adult, she deliberately chooses to occupy the same space with him and challenges him into having contact with her as a provocation for him to verbalize his disgust. He does not take the bait and regards her silently and warily. When he listens to the news, he glances at her suspiciously, but he keeps his concerns to himself. He keeps tabs on her late-night arrival. These moments are crucial for when Vincent and Alexia meet later.

“Titane” examines gender norms, the intersection between vulnerability and violence, but Ducournau refuses to let us get comfortable with the reframing. We do not get tables turned so we can cheer on a vigilante. We get a dangerous killer who happens to be a woman who will victimize anyone regardless of culpability or gender. There is no feminist solidarity here as illustrated when she enters a bus with a black woman seated across from her as the bus fills with rowdy young men using sexually violent language. (Side note: I am so intrigued that two women directors from different countries focus on women’s frustration over young men’s permissible public space intrusion. Check out Maggie Gyllenhaal’s “The Lost Daughter” (2021).) Her violence is about her safety and satisfaction. Helpful lesson: if someone hurts you against your objections, do not give them another opportunity to do so.

If “Titane” sounds grim, it is not. Once a viewer settles into the oddness of the story, I would classify it as a slasher comedy, sci fi body horror drama. Ducournau leans into the logistics of being a woman serial killer trying to cover her tracks or the biological realities of the union between flesh and metal. It is absurd when Alexia decides on her disguise, and it works. I am not going to spoil it, but eagle-eyed viewers will predict the trajectory if they pay attention to the news broadcast and were fans of “The Usual Suspects” (1995). She resembles Dren from “Splice” (2009).

In a film with a woman serial killer, Vincent is somehow the most disturbing character even though he only offers sanctuary and unconditional love to her. Alexia is understandably suspicious of his male dominated world, which is warm, especially in comparison to her childhood home. The men eat and dance together-sometimes as if they are in a mosh pit, but often taking delight in the power and solidity of their bodies. It is reminiscent of the ranch hands in “The Power of the Dog” (2021), and like them, they react to her with hostility and misgiving, but they code it in homophobic language because Alexia does not adhere to their expected gender norms.

Like her dad, Vincent is also in the business of sustaining or saving lives and responding to medical emergencies as a firefighter. He is eager to connect to her, emotionally and physically. He has no physical boundaries, and because of her disguise, Vincent is touchy feely, which is usually Alexia’s trigger to kill, kill, kill. The closest that Alexia got to comforting, physical, nonsexual contact was with Jupi, a gentle giant. We never get explicit details about his back story, but during a training exercise, Vincent collapses in grief as only he sees a young boy crouched in a burning cabinet. Is it a reveal of what happened to his son? We discover that his son played with gender and could infer that one of Vincent’s regrets were not accepting his son without limits; thus why he treats Alexia in that manner. Alexia is only used to sexual interaction as a socially acceptable way to physically interact with others and does not know how to process Vincent’s affection. The viewers relate to her confusion because we are not delusional like Vincent. If Alexia’s dad is a doctor who resents healing and refuses to treat her, Vincent is the opposite. Alexia finally learns not to kill and care under Vincent’s tutelage, which includes an interesting take on the “Macarena.” The denouement is uncomfortable and beautiful in the way that Vincent gets confronted with Alexia’s physical reality and embraces her. Alexia accepts his help and learns how to give life. Only the French could have so much adult naked flesh on screen and teach us normal uses for bodies in such a strange scenario.

“Titane” deals with the theme of bodies, normal and enhanced, and their limitations. They are all strange and messy. Body modification or body/human enhancement is characteristic of Alexia and Vincent and makes their characters stand out. While Alexia was out of necessity or organic, I confess that I did not understand why Vincent chose it other than to prolong his life and vitality, to preserve his body in the same way that he preserved his son’s room.

If I had to quibble about Ducournau’s sophomore feature, it would not be hard. When “Titane” introduces a fire fighter with the nickname Conscience, it was a bit too Christopher Nolan’s “Inception” (2010) Ariadne for my taste, and it was the one time that Ducournau’s story becomes painfully predictable. I saw “Titane” soon after “Zola,” and nothing confirms my heterosexuality more than my automatic reaction to gyrating women, “Ugh, not more naked or half naked women doing stripping dance moves.” I enjoy watching the artistry of pole work, but these gynecological moves leave me cold and bored.

I have mixed feelings on how “Titane” explores the spectrum of motherhood. Ducournau’s camera never frames Alexia’s mother as a complete person. She is cut off literally and figuratively. While she obviously cares for her daughter—she holds her hand as her child leaves the hospital and as an adult when Alexia complains about a stomachache, she is oblivious to the strained father daughter relationship and her daughter’s issues. In contrast, Vincent’s ex-wife (Myriem Akheddiou, a French actor whom I am unfamiliar with, and if you know her ethnicity, please let me know because there is unspoken theme of race that Ducournau is addressing with people of color characters such as her, the unnamed woman in the bus and Adrien, but I find elusive as an American) is Vincent’s opposite in discernment. We have another image of an unwilling mother who takes an emotional journey from wanting to terminate the pregnancy to apologizing for not giving it room to grow. She surrenders to reality and returns to herself then makes the ultimate sacrifice, not that she has much of a choice, so her baby can survive.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

So does Alexia have to die to get punished for her transgressions and Vincent can get a second chance to raise a child, the next step in human evolution a la “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968)? I love that Alexia and Vincent get to find the love that they were missing and heal together. I understand that because of this emotional journey, Alexia will never kill again except out of necessity. Considering her body’s transformation, death seems like a natural consequence, but when “Titane” reveals the baby, it does not explain why her body needed an extra plate or rip apart then die. I do not like the idea that a protagonist dies so a supporting character can be made whole. I am fine with Vincent raising an emotionally stunted serial killer, but a brand new baby? Vincent is like, “I guess my son is Alexia, pregnant, giving birth and oozing motor oil/black goo instead of bodily fluids. Let’s do this.” On one hand, if you have Vincent in your corner, you never have to worry about losing his love, but on the other hand, he is a steroid abusing, aging man out of touch with reality and suffers from suicidal ideation and violent tendencies every time reality intrudes on his created world. This baby will not be psychologically healthy.

If gender is a social construct, “Titane” suggests that family is too