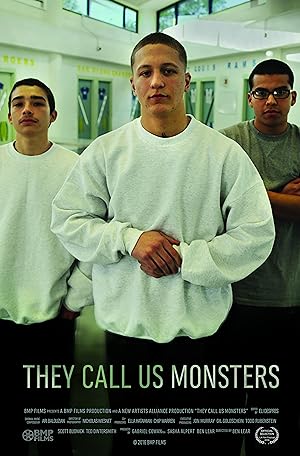

They Call Us Monsters is an eighty-two minute documentary that follows three to four juveniles being prosecuted as adults and California legislation debating whether or not to make juveniles found guilty of adult offenses the eligibility to be paroled. It isn’t quite a preach to the choir kind of film because it genuinely asks the question regarding the purpose of incarceration, rehabilitation or punishment, without giving any clear answers.

They Call Us Monsters is really two films in one. One film is a documentary that chronicles the criminal justice legal system’s journey from treating juvenile offenders as children to adults and how the pendulum is beginning to swing back to treating them like children, at least in the State of California, with the passage of Senate Bill 260. This film is only as proportionally interesting as the viewer is invested in this topic. It is simultaneously too theoretical and political and the practical result of this law is somewhat laughable. If you are condemned to several lifetimes in jail, then when you get incarcerated as a juvenile, you can get out at forty-three years old. To the victim, it may sound outrageous because this sounds like the person can still lead a full life upon release. To the offender, while it is more hopeful than life, what kind of life is it when most of his or her mature life was developed behind bars? I don’t think any good answers exist since the egg cracked long before the crime occurred.

The other film follows three to four juvenile offenders who are taking a screenwriting course while they are awaiting sentencing before they get sent to an adult facility. Gabriel Cowan teaches the course. They Call Us Monsters is more timeless when it focuses on the individual stories of these children, especially when it later juxtaposes them with the reality of the crimes that they committed and the lives that they led before and that one lives after the criminal act transpired. The documentary never pretends as if this screenwriting class changed their lives because it shows the effect that it had on one child who was found not guilty, but without any support in the outside world, he inched closer to the abyss.

The viewers and these nontraditional students are brought in touch with who they are through this class when we are not defining them on the basis of one criminal moment. It does not erase that moment. If anything, it makes that moment more startling, especially because the movie never loses sight of their victims. If these thoughtful and sensitive boys can do horrible things, then we can’t dismiss them as monsters and dehumanize them. It brings us closer to the real source of the problem, which is far more complex and harder to solve than throwing the book at them. They are our kids, and we failed them before they failed us, but they are getting punished while the rest of us go scot free. The math never quite adds up. If they must be punished and face consequences, then who gets punished for wronging them? How do we rehabilitate society?

They Call Us Monsters also unintentionally reflects how important representation is in movies behind the scenes. While Cowan does more than most of us in working with these teens, they prove to be savvy consumers instinctually cognizant of others’ perception of their tastes and allergic to negative representations. They are interested in cultivating a product acceptable to their targeted audience, their communities. They are sensitive that Cowan may see them as criminals and expect them to create a coarse product so they want to defy his expectations. When Cowan’s final product alters their initial creation, and Cowan confesses that he looked up Latina names on the Internet, it shows the limits to his liberal largesse, and their annoyance at his ignorance. When they discuss their environment, they wield popular culture like Cribs to give us a tour of their cells.

The most unintentionally alarming moment of They Call Us Monsters is the idea of prosecutorial discretion and adequate legal representation. The state will provide an attorney for the accused, but that is not a guarantee of quality; however hiring an attorney is also a crap shoot. How do you know that an attorney is good at that area of law? How much is a fair fee? The documentary briefly includes a clip of Aniko Hoover, who gives the opposite impression of a zealous advocate and alarmingly casually uses “blow,” i.e. cocaine, as a metaphor for her job. While she is probably right that the defense usually loses against the state, and I do not have any criminal law expertise, I am fairly comfortable in saying that after being a member of a legal community for almost two decades, I have never heard anyone compare an aspect of their practice with cocaine consumption. Without minimizing what these teenagers have done, which if I recall correctly, are more serious than drug offenses and involve violence, it brings to mind an anecdotal fact about prosecutorial discretion. Are more affluent communities bombarded with police stings to punish the distribution and consumption of a higher class of drugs or do we look the other way and are inclined to be more lenient if the offender fits a different demographic?

I wish that the timing of the filming of They Call Us Monsters did not coincide with the debate around California Senate Bill 260 because then it would not have attempted the ambitious goal to cover the legislative and personal side of the criminal justice system in relation to minors. The final product is less than what it could have been so if you measure your expectations, you should check it out if you’re interested in slice of life documentaries about bleak subjects.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.