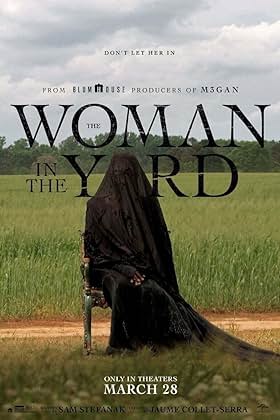

“The Woman in the Yard” (2025) takes place on a Georgia farm of a family of three: widow, Ramona (Danielle Deadwyler), older child, Taylor (Peyton Jackson), nicknamed Tay, and younger child, Annie (Estella Kahiha). They are in mourning after husband and dad, David (Russell Hornsby), the person who originally wanted the farm and was renovating it, died. One day, dressed from head to toe in black with a long veil sitting on an ornately carved wooden chair, the Woman (Okwui Okpojwasili) appears and gradually gets closer. Who is she? Oh no, the mother-in-law from “The Front Room” (2024) found another Black woman to terrorize? No! What does she want?

Deadwyler is one of my favorite chameleon actors, and “The Woman in the Yard” may be the first film that I have seen where she plays a contemporary character. She remains sympathetic even as revelations and her grief-stricken negligence accumulate. Ramona is one of those parents lost at sea but tries to shore up her authority with old-fashioned methods to ensure obedience, and the trick is getting old. She is likely clinically depressed and untreated based on her surroundings and the kids’ reaction.

Ramona could be perfect, and Tay would still begin to rebel in age-appropriate ways. After Deadwyler, Jackson executes the second most difficult balancing act as a child doing his best but also could be doing better. Writer Sam Stefanak in his feature film debut did a perfect job crafting this character. He is a kid taking on an adult’s job, but his execution reflects his lack of experience. He is a good kid who wants to respect his parent, but he also wants to snap at being chided for not performing above his paygrade. He does stupid things without becoming an annoying character such as confronting his mom on her lies without realizing that it could scare his little sister or exacerbate the situation.

Annie is a character that could have just rested on her cuteness, but her precocious questions, her writing challenges and her function as the oblivious chess piece in Ramona and Tay’s fight for dominance make her something more. She is the kid who understands enough to know that mom is not up to par but does not have an instinctual feeling of contempt yet.

There are flashbacks, oneiric sequences and videos that show different versions of David. It is always nice to see Hornsby, whom I started to recognize and appreciate in a NBC TV series “Grimm.” He is a consistently reliable actor, and here he has the challenge of playing a real man, a nightmare and an idealized version without immediately giving away which one is on screen to retain the suspense until the last second. It is a more textured role than just the deceased loved one.

Okpojwasili is stunning in looks, voice and deed. She was a scene stealer, which is saying something if you are working opposite Deadwyler. She rises to Tony Todd levels of Gothic horror. “The Woman in the Yard” should not be a franchise, but if it was, it should revolve around her character and involve a different family. I do not remember seeing her in “The Interpreter” (2005), “I Am Legend” (2007), “The Blacklist,” or “Master” (2022), but I do recall yearning for more of her character, Doctor Beehibe, in “The Exorcist: Believer” (2023). Dear casting directors, please give her meatier supporting or starring roles.

“The Woman in the Yard” should work. It is perfectly acted. The single location is evocative and haunting. Director Jaume Collet-Serra, who is better known for his Liam Neeson films (“Non-Stop,” “Run All Night,” “The Commuter”) and probably does not want to be known for “Black Adam” (2022)—I enjoyed it—does some of his greatest work on this film. The shooting and editing probably predates the theatrical release of “Nosferatu” (2024), but the way that the Woman’s shadow stretches forth and affects people is realized similarly in this story set oceans and over a century apart.

This film is going to irritate people expecting a traditional supernatural film and disappoint people who understand exactly what they are watching when it pulls punches at the end. “The Woman in the Yard” is an expressionist horror film, which creates supernatural scenarios that act as metaphors for real life. In this case, the overt mythology within the movie’s universe is not the point or solution. Most expressionist horror films can feel a bit unsatisfying at the end if you are just expecting the standard horror movie mythology such as “It Comes at Night” (2017), “Relic” (2020), “Master” (2022), “Rounding” (2022), and “The Haunting of Hollywood” (2024).

Dear Stefanak, are you ok and getting therapy? Were you the parentified child and/or the person suffering from depression. “The Woman in the Yard” is about depression and the destination that it could lead to if untreated.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Most of “The Woman in the Yard” occurs in Ramona’s mind and is a struggle not to commit suicide. She is the woman in the yard. The Woman is her shadow self who wants to give in. When she imagines killing her children, it is not literal, but it is about killing her reason to live (I hope). So she did send the kids to the neighboring farm to get help so she could die without them witnessing it. Or she died, and in death, finally could enjoy an imagined life. Either way, the happy ending felt unrealistic considering the unrelenting buildup.

I have one question. Was the car wreck an accident or an attempt gone wrong—a deliberate murder suicide? Women usually kill their children when they are post-partum if untreated and severe (Andrea Yates), but men can be family annihilators at any time, and their actions are not usually linked to depression. If I had a problem with “The Woman in the Yard,” it was creating the ambiguity that Ramona was capable of murder.

“The Woman in the Yard” feels as if it is in conversation with “Never Let Go” (2024), another film that wanted to tackle undertreated mental health issues that Black people face, but did not have enough of a sophisticated understanding of said issues to succeed. It correctly sets it in the South but is at sea when it comes to subtlety referencing the antebellum era and post traumatic enslaved syndrome without being academic. It may not have even occurred to the filmmakers that such allusions were an option. On one hand, depression and other mental health issues are universal human problems, but once Black people are cast, even if the filmmakers are not, there is a secret sauce missing that makes it fall flat because they care more about making it relatable, which flattens it, instead of making the details specific. When films embrace the building blocks of that character going back generations, it reaches more people because moviegoers recognize the overlap and appreciate the differences.

“The Woman in the Yard” felt as if it made some veiled references to “Hereditary” (2018) with the model house and the artist studio. Also it was clear that Annie was a manifestation of Ramona’s inner child and her self-condemnation of her dyslexia (?) and Tai too—her inability to be patient with herself and disgust at not being the best mother that she needed to be. The attic scene was giving “Poltergeist” (1982). For a Blumhouse film, it was audacious and ambitious, but the critical reaction may be discourage them from continuing to go for the elevated horror, artsy fartsy prize. Don’t scrap it. It just needs work. If “Nightbitch” (2024) was less palatable and safe, it would be “The Woman in the Yard.”