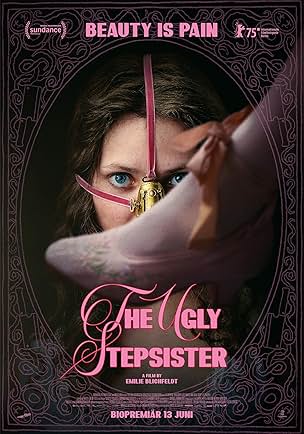

“The Ugly Stepsister” (2025) is Norwegian director and writer Emilie Blichfeldt’s feature debut. Think “The Substance” (2024) adapts the Brothers Grimm’s “Aschenputtel,” which translates into “The Little Ash Girl,” except if “Cinderella” was told from the stepsisters’ point of view. After reading a book of poems that Prince Julian (Isac Calmroth) allegedly wrote, Elvira (Lea Myren) lives in a fantasy world imagining that she will marry him, especially now that her mother, Rebekka (Ane Dahl Torp) is marrying Otto (Ralph Carlsson) and moving Elvira and her little sister, Alma (Flo Fagerli), closer to the castle. Her dreams falter when she meets Otto’s daughter, Agnes Angelica Alicia Victoria von Morgenstierne Munthe of Rosenhoff (Thea Sofie Loch Næss), the beauty standard that her mother and Elvira realizes that she must compete with to snag a prince. What does it take to change everything about Elvira?

Elvira was never physically ugly and inside she was eager, open and hard-working, but over the course of one hour forty-nine minutes, her demented beauty regime transforms her into an ugly person inside and out. Is Myren a shapeshifter or are the makeup artists that good? Other than Florence Pugh, I have never witnessed an actor actually start the movie looking like a baby then end looking like a grown woman when the actor is a grown woman! It is devastating to witness the soul killing of Elvira and her fleeting moment of happiness is not for her true self, but a brief reward for destroying herself and creating a Potemkin Village out of her body that is already collapsing under the unflinching tutelage of all the adult women around her.

Torp as Rebekka is devastating. She reveals flashes of humanity that her character then stomps out for scraps of survival beginning with Otto revealing either a playful or cruel thread in his character when he tosses cake at Elvira. Rebekka looks horrified for a moment, but because Elvira is just so happy to be there and does not take it in a negative way, she ignores her maternal instinct, and it never reemerges again though there are two moments at the end where she permits the horror of her actions to register before she stays the course. Though still hateful, Torp makes Rebekka into the image of a how a woman who cosigns society’s actions when it is her daughters’ turn to go through the mill.

That mill is a finishing school that Miss Sophie von Kronenberg (Cecilia Forss) and Madame Vanja (Katarzyna Herman) run. Vanja is blunt in her cruelty and Sophia is the good cop who seems kind, but her encouragement is as damaging as Rebekka’s. When Blichfeldt reveals their role in society, it is interesting how they feed from and hold up a system that they do not personally adhere to. Unlike Rebekka who sacrifices herself to a lesser but no less horrifying extent as her daughter, they pair offer a countercultural complicitness that feels insidious for not being transparent about other options of being a woman.

Agnes is a more complex character than the fairy tale version of Cinderella. Like Elvira, she starts off open, welcoming and maybe a bit protective of the new additions to her family, including stopping her father from throwing cake at Rebekka, but once her life gets stormy, her snobbery comes out though it is the only time she is deliberately cruel to Elvira and given the context of Elvira’s childish actions at a harrowing time, is quite human and relatable. It is never stated why Agnes shares Elvira’s goal other than pure practical recognition of her circumstances and assessment of what she has going for her. While Elvira lives in a fantasy world, Agnes suffers from no romantic delusions. There is some magical realism in her storyline, and her fairy godmother’s appearance makes sense given the context of how disturbing “The Ugly Stepsister” is. Even though she gets an alleged happy ending, based on what Blichfeldt reveals about her life and the Prince’s character, it really is not.

If there is a good guy in “The Ugly Stepsister,” it is Alma, the only revised character who comes across as new and improved in this telling. Blichfeldt shows her observing Rebekka and Elvira and learning from their mistakes. There is a throwaway scene where she becomes a woman and looks stricken because she knows what is in store for her. Her last two scenes with her mom reveal her horror and newfound motivation never to obey the lessons that Elvira did. Even though the resolution feels unrealistic, Fagerli plays her character with such silent resolve and determination that it feels possible that she can avoid the pitfalls of all the women and girls that she observed.

Men do not come off much better. Blichfeldt gets heavy-handed when depicted the male characters in “The Ugly Stepsister.” When Elvira finally sees Prince Julian, his arrow narrowly misses her but disrupts her reverie. She navigates a tiny space between two massive rocks to look through the opening at the Prince and his hunting party, which is an inherently sexual image, especially given the subsequent scenes. It does not matter how crass these men sound or how unattractive they look, Elvira remains stubbornly oblivious to allowing reality to destroy her dreams. So much for rebirth. During the ball, the men’s masticating and slurping becomes a horrifying double entendre. If these girls and women are the equivalent of food, they are prey, and these men are hunters. Only Isak (Malte Gardinger), the family stable boy, seems like a real person though how he manages to be more buck naked in the day than when he was having sex at night is an unsolved mystery.

Blichfeldt creates such a lush, textured and decayed world. Sofia Coppola’s ahistoric cultural notes within “The Ugly Stepsister” such as the music and the dance choreography combined with Ari Aster’s images of decay and sounds of harp strings from “Midsommar” (2019) signifying an idealized life inspire Blichfeldt’s vision of a realistic, yet just as fantastical nightmarish world. The level of self-inflicted body horror that Elvira endures actually made me look away from the screen. The fairy tale becomes a cautionary tale of gendered child abuse about how mothers groom their daughters into eagerly signing on to societal standards that make them believe horrible things about themselves, idealize loutish behavior if it is coming from a man, encourage them to self-mutilate to fit a standard and achieve the dubious goal of becoming the wife of a man who sees them as a product to consume. It is dehumanization and self-mutilation as a deceptive, disabling prize.

Blichfeldt’s premiere will remind body horror fans of other amazing firsts from Coralie Fergeat’s “Revenge” (2017) or Julia Ducournau’s “Raw” (2016). Out of the three, Blichfeldt may have the hardest assignment because she is working with a universal story that has ancient Egyptian origins dating as far back as 7 B.C. yet her version remains faithful despite taking liberties to tell a story that focuses on the harsh financial realities of being a woman and doing what it takes to survive. David Cronenberg’s list of spiritual directing daughters is growing, and they delight less in human nature than to warn of the suicidal side of society that demonizes the organic self in favor of the monstrous distortion when people ignore the adage, “If it is not broken, don’t fix it.”