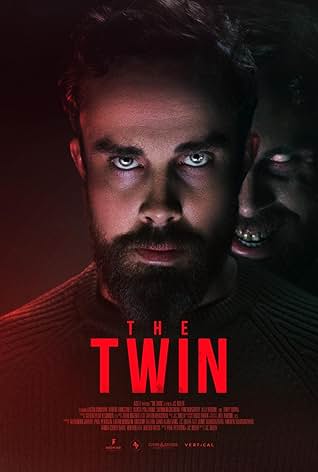

Timing is everything, and with a sudden rash of psychological horror films, “The Twin” (2024) falls somewhere in the middle of “Lilly Lives Alone” (2025) and the excellent “Descendent” (2025). This film expands a short film called “Hangman” (2016). As a child, Nick (Tucker Grumbles) had a strange experience before the death of his grandmother, (Pam Dougherty), which happens again as an adult when Nicholas (Logan Donovan) faces another tragedy. Can Nicholas learn to live with himself?

It is hard to believe that Nicholas is the same person as the kid introduced in the opening because it does not seem as if he was going to survive the night, forget make it to adulthood. Donovan establishes Nicholas as a stable, loving man until he has a break with reality and is stuck in an institution for a month. Director and cowriter J. C. Doler shows Nicholas’ perspective before showing other people’s view of the same thing, and Nicholas is an unreliable narrator. For instance, when he looks at photos, loved one’s face is smudged or scratched out, but his wife, Charlie (Aleksa Palladino), can see the photo normally. Donovan has two roles to play, Nicholas and his doppelganger, and a third if you count Nicholas pretending to be alright so people can stop scrutinizing him. Donovan makes it look natural.

Even though his grandma died when he was young, Nicholas only recently received the deed (huh), and his wife thinks that the best time to clean out the place is after being released from a state institution. Apparently, Charlie does not know about his childhood, but still, “The Twin” writes her like she is dumb or cold. On the other hand, if Doler and cowriter Paul Petersen had given more thought to the character, Charlie would be the personification of “I gotta choose me first, Lucius.” Palladino is left doing all the heavy lifting and filling in the blanks. Costume designer Taylor Bracewell also deserves credit for dressing stable Nicholas in the cardigan of credibility and Charlie in a black suit to indicate that she is all business. At the end, it is revealed that she was working a day job so he could stay home and be the worst painter ever—think paint bar levels without the wine as a cover story for the quality. That woman was in love and is all heart. Look at “The Twin” redeeming “We’re Not Safe Here” (2025), which had a worse story, but better art.

Two actors were having the best time filming “The Twin.” The first one is Robert Longstreet, who resembles Russell Crowe, playing Dr. Andrew Beaumont. This unconventional therapist should come with the label “do not try this at home” because his methods, especially in the denouement seem wildly dangerous and a one-way trip to a malpractice claim. It also means that he is fun to watch. He shares too much about his life. He calls patients on their shit. He also seems to think that informed consent to treatment is optional. Longstreet makes his character likeable despite all evidence to the contrary. Also, he believes in hypnotherapy, which is not proven to unlock accurate, repressed memories, and in the wrong hands, leads to Satanic panic. This movie is not that and seems to be ignorant of such implications.

The second scene stealer is Shannon Cochran, who plays Shelby, grandma’s neighbor and now a grandma herself. Damn, Doler and Petersen missed an opportunity to build that up into more than a way to show how outsiders objectively view Nicholas’ behavior. Shelby waited all her life to talk about the night that grandma died, and when Dr. Beaumont asks questions, she does not stop answering. Hell, she ropes in the wife closer to the denouement to tell tales of Nicholas past and present. She is such dishy fun in “The Twin,” which is as serious as a heart attack. She also introduces the concept of The Fetch.

Oh yeah, “The Twin” is another psychological horror film about grief, but at least there is a folklore figure that is not often used in movies, so this movie has something going for it. It makes visual allusions to “The Doctor’s Fetch” complete with illustrations. A fetch appears before someone dies and is a person’s doppelganger. Doler’s best imagery is showing how The Fetch slides its hand over Nicholas’ body or wraps its hands around his neck. The best scene is when they merge, and its grey hands overtake Nicholas. Nicholas paints differently under its influence. The main question: is it real or not?

“The Twin” wears out its welcome. Once a character explains the whole plot to the audience, it is time to wrap it up. Also, Petersen and Doler want to have their cake and eat it too because characters who feel guilt over a loved one’s death do objectively hear things and occasionally see things too, but on the other hand, people who are not vulnerable to grief see nothing. The Fetch becomes a metaphor for self-condemnation and the threat of suicidal ideation. It is heavy handed, but visually Doler translates it well with the lighting. The nightmare world is also distinct from the waking one.

The objective contrasts sharply with the short film, which frames the phenomenon around mental health concerns and does not offer a tidy backstory that explains the condition. Too often, movies eschew the use of pharmaceutical drugs as the establishment trying to destroy uniqueness in talented, outlier individuals. “Hangman” did the reverse. Instead of Nicholas being exiled in his time of need, Nicholas Schultz (Chris Alan Evans, who makes a cameo in “The Twin”) is self-isolating from anyone helpful and eschewing anything that could possibly eliminate his tormentor if imagined. Doler cowrote that film with Evans and his wife Taylor Bracewell, who doubled as the cinematographer. If the expansion remained faithful to the original, the film would have been a more original, daring, countercultural film. The solution would change from wrestling with your inner demons and being forgiven to accepting community and taking helpful advice. Instead, the feature makes the drugs feel ineffective compared to a night spent confronting your subconscious. In an era when the Secretary of Health and Human Services rejects conventional medicine, it would have been more radical to emphasize the effectiveness of hard work and show the phenomenon decreasing. Instead Doler leaned on the monster while simultaneously undercutting it.

In a vacuum, Doler’s feature debut is a solid movie, which is visually superior to the original, but “The Twin” seems more concerned with reassurance and exculpation. While no one should listen to intrusive thoughts, and Nicholas was not at fault as a child or an adult, in a world bent on reassuring men and minimizing wrongdoing, it is a stale concept in contrast to the original message. Doler had a chance to really wrestle with mental health in a realistic way and make an original horror film. Doler has great ideas and a wonderful eye, but he just needs to work on following through with his vision.