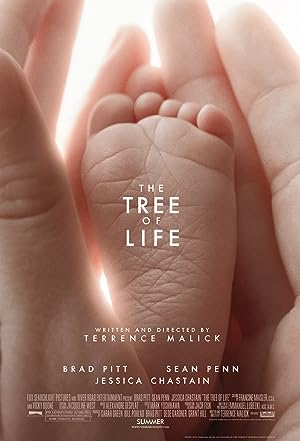

Terrence Malick directed The Tree of Life, an experimental drama about the eldest child and his parents grappling with sorrow, their individual failings and their relationship with God. It stars Jessica “I’m the motherfucker that found this place” Chastain as the mother, Brad Pitt as the buzz cut father to show that he can act and is more than his looks and Sean Penn as their son, Jack O’Brien, once he becomes an adult.

After seeing a handful of Malick movies, The Thin Red Line, To the Wonder and A Hidden Life, I am convinced that Malick should never allow his movies to be shown anywhere but in a theater and have an arrangement where certain theaters can have a retrospective around the world if people want to catch his movies if they missed the original theatrical run because there is no way to capture the scope of what he is trying to do on the small screen, especially since it requires that the unconventional narratives and the sweeping movement of the characters and the camera transport the viewer, which cannot happen unless you are in a dark room with no other options for stimuli in front of a big screen and other people to enforce these rules if you get tempted to seek out distractions. I do not think that it is a coincidence that I enjoyed A Hidden Life, which I saw in the theater, but while I can intellectually appreciate what Malick is trying to do, Malick’s ponderous approach to human stories opens itself up to ridicule in more quotidian settings.

The Tree of Life is an ambitious movie that tries to respond to God’s question posed in Job 38: 4, 7 “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth?…when the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?” Malick’s movie is apparently semi-autobiographical, and like Job, which are the son’s initials (GET IT!), he is trying to get answers from God by placing his story within the overall context of life in the entire universe. Thanks to the magic of moviemaking, he can be there when God creates, and Malick’s image of God or at least the mysterious spark of life is reminiscent, but less solid than a candle’s flame, which is where the narrative starts. The following is my interpretation of the story, not necessarily a definitive reading of the movie. At points of birth and death, people exist on an eternal plane that makes it possible to exist at all times. As an adult, Jack dies on the anniversary of a loved one’s death and reflects on his life, which includes the point of creation, and reunites in the afterworld, which in Malick’s vision is a beach with people wandering around, but his life is strictly focused on his childhood and last day on Earth, not the point when he first leaves his home through adulthood, because I suppose that is the most memorable and pivotal point of his life. When the story starts, we partially get to witness his mother’s point of view and her wrestling with God, which includes her early days of motherhood and a point of terrible loss.

The Tree of Life is like Nova without a narrator with a long impressionistic snapshot of an American family’s life in 1956 Texas. For the viewer who can relate intimately to the latter and consider it a universal story, daddy issues and being a little shit as a child help, this kind of storytelling will imbue your life with a beauty and significance usually missing, but for those of us looking from the outside in, it leads to a dispassionate, meandering viewing that makes it difficult to engage for the entire two hour nineteen minute run time. I have less of a problem with the experimental scope than the narrative order.

I would have preferred if The Tree of Life started with the flicker and the whispers, the literal Biblical creation meets scientific documentary CGI story before embarking on the human story. Alternatively if the story did not include the mother’s, but was restricted to Jack’s story starting before he leaves his home, I believe that it would have worked better. Another option is to divide the movie into thirds-the first third is the mother’s story, the second third is the experimental creation narrative and the final third is Jack’s story. Malick’s story rests on an assumption that the mother’s most important points of time were early motherhood and mourning a death of a loved one, but I do not necessarily rely on that assumption unless she agrees. It feels as if Malick is still a child that believes a mother’s life revolves around her kids. It may, but there is a point in the movie when kid Jack shouts, “She loves me the most,” and the film structure feels more like that. I understand that he loves and idolizes his mother, but when you are aiming for combining the subjective experience of Jack and his mother and the objective, eyewitness experience of creation, either the subjective experience of the mother should be from her perspective or the objective eyewitness cannot exist. It is all Jack’s experience. I definitely did not want the movie to be longer, but I felt that we were cheated by not getting to see the father’s subjective experience instead we just get the resentful version as understandably seen through the eyes of a child.

Child Jack has every right to have issues with his father, but similarly his father’s story is very relatable in a way that artist Malick, who must be deeply fulfilled in his work and ambitions, never truly emphasizes with. I can understand why his father would metaphorically kick the dog at home while not condoning it. Jack was witnessing his father’s gradual disillusionment with the promises of the world that if he worked hard and did certain things in a certain way, a path that he was eager to teach his kids, he would succeed. He experiences the death of hope, and while Malick intellectually understands and conveys it, he has never been able to separate himself from his childhood subjective experience of resentment. He does not tell his father’s story in an adult way because he does not see it as such. He still primarily sees it as a story in which a father dominates a family to feel important and hurts him and his brother until they flinch away from his awkward gestures of warmth, which lack the same conviction and directness as his punishment.

The Tree of Life shows that Malick has two images of God and himself. God is the New Testament God as symbolized by his mother, the path of grace. God can also be the Old Testament God as symbolized by his father, the path of nature, but I do not adhere to this simplistic image of God in the Old Testament, nor do I believe that Malick does so his father is also a symbol of his fallen self. For me, they were all a symbol of the bankruptcy of American human life at its worst with an artificial hierarchy superimposed on life to create a cycle of rationalization that it is permissible to hurt others. Even though I understand that plenty of little boys will see Jack’s actions as ordinary, I considered him a little serial killer in the making, and if this behavior is normal for packs of boys, no wonder when I see a group of young boys, I instinctually shudder and am suspicious.

I cannot recommend The Tree of Life if you are watching it on the small screen because it is utterly unwatchable in that format, but it is objectively considered one of the greatest movies of all time. Stanley Kubrick and Ridley Scott are probably seething with jealously that Malick had the courage to tell a story that way. I think that it needs a little work, but appreciate the intention.