When you’re raised fundamentalist, anything fun is considered “of the world,” and Sundays were the worst because you weren’t allowed to do anything secular, i.e. anything not related to the church or the Bible. I actually like (my) church and the Bible, but nothing sucks the joy out of anything more than making it an obligation. Fortunately there are exceptions to any rules. Long before I discovered Christian produced movies, there were Biblical epics that originally appeared on the big screen or were television movies. These movies were actually good because they had real actors, quality production values and solid stories with authentic human emotion and drama. They bridged the gap between the prosaic and the miraculous by making it possible to empathize with these people.

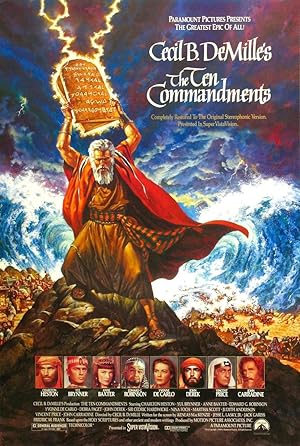

So it isn’t a surprise that like millions of Americans, I have an unreasonable fondness for The Ten Commandments (1956) starring Charlton Heston and Yul Brenner, which airs on ABC the Saturday before Easter to satisfy Jewish viewers celebrating Passover and Christian viewers getting ready to go to church and tell each other, “He is risen. He is risen indeed.” Cecil B. DeMille had already made a movie with the same title on black & white film, but it is easy to forget it compared to the 3 hours 40 minutes, an insane length for any movie, household epic. It occasionally feels too short considering how abbreviated the movie is after Moses and the Hebrews leave Egypt. Love it or hate it, you’ve probably seen it more than once.

Numerous people may say that the acting is bad. Judged by our standards of naturalistic acting, it is, especially the staging as people talk to each other in profile on their best side or staring straight into the camera. They don’t deliver their lines as much as they declare them. I love classic Hollywood movies so if it isn’t your thing, I’m not mad at you, but the movies weren’t the only thing that was grand. “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.” Tell me that it isn’t delicious how Brenner basically struts like a peacock on the runway for the entire movie. My favorite exchange is between Moses and Zipporah, “Your eyes are sharp as they are beautiful” then she stares into the camera for like five minutes. Love! Vincent Price had a bit part. Come on! Real talk: Moses was hot.

Sure the dialogue is ridiculous. People don’t talk like that in real life, but coupled with the over the top acting, it is fabulous. If I returned to watching The Ten Commandments (1956) annually, I’m pretty sure that I could deliver the lines as they appear. It is my Rocky Horror Picture Show, but better because the story hits hard. No, really, it is a good story.

The Ten Commandments (1956) is office and family politics taken to the extreme. You’ve got this guy killing it on all fronts: his boss/uncle loves him; foreigners that he was about to go to war with love him and end up singing his praises. He genuinely does a good job, is completely disinterested in power struggles, treats everyone with respect and dignity, including women and slaves, and loves his family for who they are, not what they can give him, but he moves from project to project because he is told to, not because he is innately invested in it. He does not have a life purpose other than the one sketched out for him, and he is happy to keep going down that track, but the way that he operates in the world brings him into conflict with his culture and family even though he gives them what they want. The revelation about his origin does not create an identity crisis, but severs his attempts to please the world that he was serving and makes him question the way that he was brought up, which he already did subconsciously. He hasn’t changed so it seems absurd to him that he should be treated differently because of this one fact. He takes it one step further—if he shouldn’t be treated this way, then no one should. He understands the difference between right or wrong, the innate dignity of all living creatures to be treated well, long before he meets God and accepts Him. He only accepts God because Moses discovers that God agrees. Before Moses knew of God, he unwittingly accepted His values. If God did not reflect those values, then Moses would have rejected Him too just as he rejected Pharoah, whom Moses loved, and the gods of Egypt. Similarly we should reject any characterization of God that does not reflect these values.

What I love about The Ten Commandments (1956) is how all these people orbiting him have these full complete lives that intersect with him in a small way, but in off-handed seemingly random moments that actually have a huge effect and start to change his path. We, as the audience, know more than they do about the overall trajectory of the story, and we get to see everything while the characters do not without it feeling onerous. Even without the knowledge that they are making a difference, they are. I love the idea that before knowing God, people living daily contribute to His plan regardless of whether or not their actions are good or bad, even if their actions are not made with the intent of serving God. It takes away the pressure of making mistakes when mistakes are part of the bigger picture, not something that condemns us. It also makes the movie funny because it injects even the most solemn scene with an idea missing from many pulpits: God has a sense of humor and is laying joke grenades in their life.

Simon: Thank you, my son… but death is better than bondage, for my days are ended and my prayer unanswered.

Moses: What prayer, old man?

Simon: That before death closed my eyes, I might behold the deliverer who will lead all men to freedom.

Moses: What deliverer could break the power of Pharaoh?

Egyptian guard: You!

As an adaptation, The Ten Commandments (1956) does a superb job of elaborating on a story in a credible way. Usually people complain when movies add to the Bible, but DeMille’s conception of Moses as a character has so informed our way of thinking about Moses as a person that many don’t realize that we are thinking of DeMille’s characterization, not something that was actually written in the Bible. We have no idea if Moses was good at his job—that was Joseph. Considering that he farmed out a good portion of his job to his brother, he may not have been. Ben Kingsley’s depiction of Moses as a shy guy was probably more faithful to the real life person if the Bible’s account reflects reality. There is nothing about the Egyptian royal family’s relationship with each other. Luke Chapter 2 probably inspired that exchange between Moses and Simon. Hey, if you’re going to take story ideas from other writers, it probably helps to take it from the same anthology.

The dialogue and the acting style may be outlandish, but the human emotion and motivation behind it is not, and DeMille effectively fleshes out the story. For example, Rameses was all about the power, but we also see him as a guy trying to reclaim what should have been his without question: his father’s love, his fiancée’s admiration. Sure he never treated them like human beings so they never reciprocated, but he does not see it that way. On some level, he is right to be aggrieved and see Moses as a usurper before he knows the truth. Rameses was the paragon of his lessons: using people because of his station in life, not empathizing with others because of that entitlement from birth. How could he be punished for living the way that he was raised? He is trying to restore order. He is excellent not because of his work or his attitude, but because he is a prince. Sound familiar?

How do you recognize God? Is it because you did what you were told without thinking about it then expected a reward from God, but reacted bitterly when you didn’t get it? Or did you question what you were told and searched for God on your own to demand not a reward for yourself, but justice for others and the elimination of evil from the world? If the God that you worship cares not for these concerns, then maybe you’re worshipping another God.

Maybe you don’t care about God and just like movies. After watching Peterloo, which Mike Leigh, one of my favorite directors, directed, two hours thirty-four minutes feels excruciatingly long though similarly well-intentioned in trying to exhaustively explore and depict socioeconomic conflict that led to a pivotal turning point which eventually led to the suffrage of the common people. It is earnest and unwatchable. The Ten Commandments (1956) is similarly trying to stir its viewers to nobler, egalitarian principles while not neglecting the human side of the story and never neglected the salacious side of humanity. I hate gratuitous sex in films, but to pretend that people just deliver speeches all day is pure fiction. DeMille knows how to keep people entertained for hours without anyone complaining. Movies aren’t supposed to taste like vegetables.

Honestly The Ten Commandments (1956) is such a classic that if you have never watched it as a kid, I have no idea how you’ll receive it as an adult. I’ve seen worse special effects from contemporary films, but obviously the movie is dated. If you’re not into classic Hollywood, then either this movie will be the worst or best introduction to it. I’m too biased in its favor to imagine looking at it as anything but a sheer delight.