“The Starling Girl” (2023) refers to Jem Starling (Eliza Scanlen), the oldest daughter in a Kentucky Christian fundamentalist family. She tries to be good and follow all the rules, but anyone can criticize her for falling short just by existing. When married youth pastor Owen Taylor (Lewis Pullman), older son of the pastor (Kyle Secor) and older brother of Ben (Austin Abrams), who is courting Jen, encourages and reassures her, she starts looking for excuses to interact with him, which he also encourages. For Bible fans, when she ties his shoelace, it is a double entendre: a reminder of Jesus’ humbleness and washing feet, but also feet can be a euphemism in Ruth.

I was brought up fundamentalist Christian, but in Manhattan so while I had some checks and balances to the doctrine, I recognize the language and understand how dialogue, which sounds insane and screams red flag, under the right circumstances, sounds caring and right so while the characters in the more repressive and isolated “Women Talking” (2022) are prepared to argue a dissertation on how problematic their community is, “The Starling Girl” is more realistic because while most of the characters on some level know that something is off, they believe the problem lies within and is not systematic.

Jem is seventeen years old, but she is a kid who still gobbles food from a well-stocked table, preferably powdered donuts, is not interested in courting and is more interested in playing and dancing. Left to her own devices, she may have fulfilled the community’s demands for purity, but her community grooms her by never letting her forget that her body is inherently wrong, sexual, sinful so she needs to get hitched to someone quick. Any adult can tell her what to do with her body, so she is used to obeying adult demands without question—lie down, spit out gum, etc. It is a brilliant moment to show a well-meaning congregant embarrasses her, which results in her running out to grab a literal predator’s attention.

Watching “The Starling Girl” is scarier than watching any horror movie. Owen’s appeal is obvious. He is exotic because he cannot stop talking about distant lands (Puerto Rico). His father considers him outlandish for suggesting that an activity for the congregation’s children is *gasp* farming. His hair is long for the men in that church. He wears black t-shirts and jeans. Writer and director Laurel Parmet never takes the easy route by making him or anyone else into monsters though she gets close. While we can see Owen coming from a mile away, Parmet leaves enough room to show how he too feels legitimately stifled, trapped in a life not entirely of his choosing. To quote “Women Talking,” “aren’t you suggesting that the attackers are as much victims as the victims of the attacks? That all of us, men and women, are victims of the circumstances….In a sense, yes.” Owen sins in two ways: by taking advantage of a kid, who consented to one thing, but not another, and by infecting God’s message of no condemnation with suspicion that it is an evil message because Owen used it to justify his manipulation.

Everyone in “The Starling Girl” finds a way to self-medicate in secret: secular music, sex, alcohol, drugs, cigarettes, pills. The pain of not living fully and freely eventually overtakes all and destroys the appearance of fitting in. Jem’s dad, Paul (Jimmi Simpson), is just the first one to flame out spectacularly. Paul equates art with selfishness: his music and his daughter’s dance. Being an individual instead of another interchangeable widget who exists only to serve God is forbidden, and the entire community is driven to stomp it out of Jem until she is almost left with nothing and blamed for everything—a little girl who is not even allowed to do anything without the supervision of the nearest male or older, married woman. How powerful she must be to be able to command the fate of so many by just existing!

I wanted to know more about Owen’s wife, Misty (Jessamine Burgum), after she openly snapped at Owen at a gathering after he kept going on about dancing in Puerto Rico, “When would I have seen it?” Did she go with him? Was she too busy doing women’s work to enjoy the missionary trip in the same way? How come she could snap without getting rebuked? Was it because she was cosigning the community’s standards, rebuking him for showing admiration for other cultures instead of God? I suspect the latter. Fundamentalism can be grim and joyless demanding that nothing can be enjoyed unless it is related to God. Jem’s choice of dance music is questioned because it is a Christian pop song or has drums.

I wanted to know more about Jem’s little sister, Rebecca (Claire Elizabeth Green), who does not get much screen time, but makes the most of it when she does. Jem seems like a child who still believes in fairy tales compared to her perspicacious sister. If I watch “The Starling Girl” again, I’ll pay closer attention to her because unlike Jem, she seems to understand more about the world and her community than even the adults. She is a real one prepared to be the best sister ever but too young to do more than be the first flawless Christian, non-judgmental and protective, a witness to the community’s hypocrisy.

“The Starling Girl” ends on an ambiguous note with most of the characters’ future undetermined. The only person who is unchanging throughout the entire runtime is the pastor. Even Jem’s mom, Heidi (Wrenn Schmidt), a stern disciplinarian and zealot who uses her husband’s despair to push her own ambitious agenda by steering Jem’s life into marriage or exile. By the denouement, her journey veers in polemic directions. It would be interesting to drop in on her in a year to see where she lands. I love when women get angry.

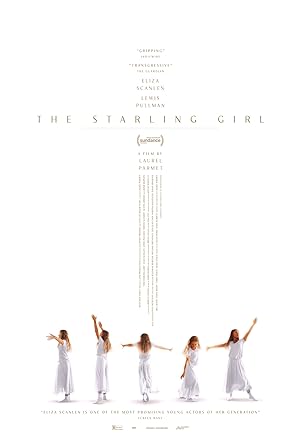

Permet still tries to end “The Starling Girl” on a hopeful note because wherever you go, there you are. Jem’s story covers a wide dramatic range of circumstances from the one with the best prospects of getting admitted into the kingdom of heaven to the disgraced outcast, but regardless of the circumstance, she is still dancing. It is interesting that the box office is filled with adolescent girls praying to God—“Are You There, God? It’s Me Margaret.” (2023). Whenever Jem gets upset, she plunges into the nearest body of water, a symbol of God. In Jem’s case, her relationship to God is related to the important men in her life, Owen at the top of the stairs in the beginning, judging if she is “mindful” and her father’s iPod, an answer to her last prayer, which offers her direction though it is unclear whether the events after this dance will go better than the first.

Jem has changed, but she is still the same: an individual. I highly recommend “The Starling Girl,” especially for any (former) Christian who had to go through a deconstruction era.