Pedro Almodovar is one of the greatest living film directors, the rightful heir to Hitchcock’s throne with his mix of psychosexual driven dramas and an innovative storyteller who delivers uniquely crafted narratives. When Hulu notified me that his films were going to expire and be removed on June 20, 2017, I decided to watch all his films, including the ones that I already saw. This review is the seventh in a summer series that reflect on his films and contains spoilers.

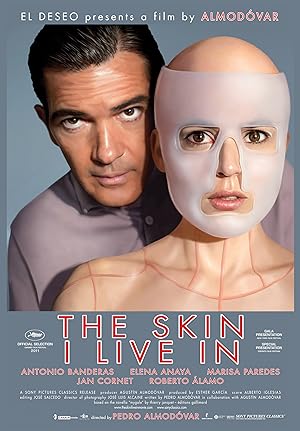

The Skin I Live In may be my favorite Almodovar film EVAH (spelled incorrectly for emphasis). Usually when I see one of his films, I know nothing about the film except the title. I first heard about it when people who clearly never even heard about Almodovar were clutching their pearls at the plot and saw this film as one of the horsemen of the apocalypse, a sign of corruption in the heart of Hollywood, a deviant work. There were plenty of spoilers, but they were wrong: a doctor performs a sex change on his daughter’s rapist, makes him look like her then rapes her. I must admit that the idea of giving the rapist his daughter’s face and raping her gave me pause and was when he would have lost me, but I was willing to reserve judgment because I trust Almodovar, and the spoilers got it wrong.

Honestly if Pedro casually said that he was taking a crap and charged people to see it, I would stand on line, and it would probably be more magnificent than most of the movies that exist. People who ARE familiar with Almodovar’s work know that simply describing his plots sounds like sensational, jump over the shark drivel, but watching it is as if you have stumbled into a world more alive, absorbing and vibrant than the one that you live in with the possibility of it all making sense. I knew that I would see the movie, but when and how were the variables.

Just under six years later, I finally saw the film by streaming it, and I watched it almost two times in a row. The Skin I Live In takes our revenge fantasy of meting out justice on a rapist by castrating him and then letting him experience rape (but not by the doctor) then ends up subverting it. Instead Almodovar uses his film, a terrific blend of sci-fi and horror, as an empathy machine to make audiences realize how a person feels when he or she is born with the wrong gender and forced to live that lie to survive, to conform to an image of how you should look and act. This analogy is also applicable to sexual orientation-because of one’s gender, there is an assumption that the person is attracted to the opposite sex and is expected to act accordingly.

The Skin I Live In condemns society’s demands on an individual’s identity as cruel and insane by equating it with a mad scientist played by Antonio Banderas. Banderas’ characters in Almodovar films are not overly troubled by concepts such as consent, get away with a lot because of their sensitivity, beauty and skills and are usually batshit crazy, but it is always a surprise when contrasted with Banderas’ less textured American career where we just thought he was sexy and macho then called it a day. In this film, he plays the grief-stricken and mentally disordered, but successful and brilliant doctor. There is some question of whether or not he was delusional from birth, a doctor with a God complex or if he was triggered by his wife’s affair, accident then suicide, his daughter’s breakdown at witnessing her mother’s suicide, being raped or sexually assaulted, rejecting her father because she thought he raped her then suicide.

Because The Skin I Live In is an Almodovar film, our image of the mad scientist is a beautiful, seductive and enticing one. Initially the movie introduces him as objective sober, benevolent, empathetic and innovatively brilliant lecturer. His estate is not the cobweb-covered fortress of Dr. Frankenstein on a hill. His home is sumptuous albeit a little cold. It is filled with art, specifically large images of women. His employer has so much faith in him that he has an operating theater and laboratory in his home. It is only upon closer inspection that we realize that something is wrong. Why is there a woman locked in a room with constant camera surveillance? Why is he watching her on the surveillance screen like she is another work of art? Wait, she has pig skin?!? I thought this was Dr. Frankenstein, not Dr. Moreau. Why choose! At another, subsequent lecture, it becomes clear that this doctor has violated the laws of nature and medicine. On his estate, he can kidnap, experiment, threaten and kill with impunity even from his disapproving colleagues.

This estate seems to have more in common with the cursed, blood soaked earth of a Southern antebellum plantation than any ordinary estate. The Skin I Live In uses numerous complex narrative techniques to allude to the land’s generational curse. It is a place where the owners can be Pharoah, take a servant’s child then make him their own while exiling another. (Is Mr. Legard the father of Dr. Legard?) No one seems to question the ethics of a husband treating his wife. It is a place where women feel compelled to flee and eventually go mad and die if they don’t. There is even a garden and a fall. Cain and Abel conflicts play out except it is more civilized veneer Cain vs. brutal Cain. Brothers in Almodovar films are never as harmonious as brothers and sisters or sisters. The ordinary rule of law does not seem to apply to this land. Dr. Legard is possibly just one in a long line of Legards who used this estate to live out his fantasies with no regard of how it affected others.

Almodovar’s films usually focus on flawed people, including pedophile priests, but ordinarily he does not equate the church with God or spirituality. The Skin I Live In’s Dr. Robert Legard is the first time that Almodovar gives his audience a pessimistic view of a God figure. He demands love even after being rejected and despite his actions deserving none. Bad things happen to people in his care, specifically his daughter, so his power and status benefit no one. His origins are mysterious, particularly his father. He can usually act with impunity and has the power to transform people. In Almodovar’s later films, the medical profession, which he depicted in earlier films as a protector and an ally, is now an aggressive perpetrator with the power of the law. Dr. Legard becomes Pygmalion, but he sculpts the Scylla and Charybdis, not Galatea.

The Skin I Live In’s narrative unfolds in unique ways reminiscent to Broken Embraces, but even more ephemeral. Almodovar has the unfolding present, stories told by witnesses to others with either the depiction of the imagination of hearing or telling that story (scary stories told by the fire), getting a peak into dream memories of the same events from different character’s perspectives. The film feels more like a deranged fairy tale than real. Iconic figures lurk everywhere: the tiger seeking to devour, the phantom mad woman in the tower, the kidnapped beauty in jeopardy locked away.

The Skin I Live In is the first time that an Almodovar film does not begin with a performance of some type although one can argue than the captured beauty doing yoga on the sofa is a type of performance since s/he is forced into that room and framed by surveillance cameras for others’ consumptions. The only theater is a medical theater. S/he can sense when others’ gaze at him/her, and like Pepa in Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, tries to use this fascination with him/her performance to him/her advantage by returning that gaze and reflecting the viewers’ desire. S/he is conscious of this power because of her identity-s/he was the person who raped/sexually assaulted his daughter and is used to manipulating women’s bodies in real life and in sculpture. He is also a Pygmalion type figure in the way that he tries to force women to dress then uses that skill with his/her body as the weapon.

Because of the forced and violent ambiguity of Vera/Vicente’s existence, s/he must embrace his past to survive her present. An Los Angeles Times article quoted Shirley Maclaine as inadvertently dismissing issues of women of color and transgender women by urging them to find “our inner democracy.” Upon reading that, I thought, “In this inner democracy, do I have health insurance, a living wage, autonomy over my body, an ability to live without danger from official authorities? Can my inner democracy issue checks to my outer bank account? Oh, Shirley, you are such a Unitarian Jihadist. This does not work in the real world.” The Skin I Live In presents Vera/Vicente’s yoga as his/her inner democracy, his/her ability to retain her/his identity and survive despite the practical limits of that practice. This inner democracy and current status as a vulnerable person does not diminish what happened in the past.

I’m very surprised that so many people try to explain Vicente isn’t a rapist. The Skin I Live In presents many images of rape, including a more stereotypically violent one, Zeca, the tiger, who rapes Vera/Vicente and engages in a type of oral rape of his mother by repeatedly gagging her (normally I would not classify gagging as rape, but the language that Zeca uses with his mother and Vera about fitting things in their orifices begs for the comparison). Vicente may not have intended to rape the doctor’s daughter and did not do so if there was no penetration (this film is a drama, not porn, so this point is debatable), but once she physically tried to get him to stop, even if that reason was not his fault (she gets triggered by a song linked to her mom’s suicide), it is rape no matter what North Carolina legislators and courts write. It also could be rape depending on her mental capacity to consent.

Almodovar usually depicts miscommunication through technology, but this time, he uses legal and illegal drugs. She is on prescription medicine, but Vicente thinks that she is talking about recreational drugs and partying like him. Vicente may never intend to rape, but it does not mean that he is not a rapist at most or a sexual assaulter at minimum. In earlier scenes, he sexually harasses an employee (he is the boss’ son so I’m not going to say coworker), who clearly rebuffs his advances.

The Skin I Live In is emblematic of Almodovar’s ability to create empathy for problematic characters, including rapists, while simultaneously not minimizing the harm of his actions. By introducing the rapist to the viewer as a captive beauty and a rape victim, he correctly challenges our notions of vengeance (in reality, we don’t actually want rapists to be raped no matter what we say) while giving every character an opportunity to make a revenge fantasy come true.

Almodovar tries to give The Skin I Live In a somewhat happy ending. The employee is a lesbian and rejected Vicente when he was himself, but even though Vicente is still Vicente, he presents as a woman and now may have a chance at love even though he will always be trapped in the wrong body. In this unofficial sequel to Talk to Her, the Benigno like figure gets a chance at happiness with a former victim, but with her full knowledge of his past and hers.

The happy ending is in jeopardy because The Skin I Live In presents an awkward question of the role that mothers play in the story. There are three mothers. Dr. Legard’s mother, the housekeeper, admits to insane origins, facilitates her favorite son’s sinister experiment, encourages him to kill and will do anything for him. She mothers two monsters. There is the story of another mother, who literally sees herself as a monster. In the housekeeper’s story, she abandons her husband and implicitly her child then has no further consideration of her child by permanently scarring her child with the vision of her death and implicitly transmitting the song trigger for self-destruction. The closest that we get to a normal mother is Vicente’s mother, but she has to stop her son from sexually harassing her employee and implicitly condones it by letting him work there. These mothers keep secrets from their children and consciously or inadvertently create (self-) destructive children. With one mother left standing and the audience’s uncertainty to how she will respond to Vera’s story, the ending is ambiguous.

The Skin I Live In is one of Almodovar’s most pessimistic films even though it is not as purely tragic as Law of Desire and Bad Education. This movie gave Elena Anaya an opportunity to show her acting prowess as Vera, which was not as apparent in her role as a mad scientist in Wonder Woman, and the only flaw in her performance could not be helped, her voice is too naturally feminine to be Vicente. The Skin I Live In is a battle of revenge fantasies between two shadowy, morally problematic figures, but like all Almodovar films, ultimately the truth will come out.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.