“The Seed of the Sacred Fig” (2024) is set in Tehran, Iran during September 2022 soon after a husband and father, Iman (Missagh Zareh), gets a promotion at work. His wife, Najmeh (Soheila Golestani), is excited and supportive, but has trepidations about him bringing a gun into the house for their protection. Iman’s behavior changes, and protests disrupt the family routine, but when Iman cannot find his gun, the line between his private and professional life blurs. Will they ever return to being the family that they once were, and is that a goal that they should aspire to?

Let’s get a few things out of the way before diving into “The Seed of the Sacred Fig.” Making any movie is a miracle, but in Iran, it could make you an outlaw and exile, which is what happened to director Mohamad Rasoulof. From December 2023 through March 2024, he shot the film in secret for 70 days, and the uncut footage was smuggled out. Rasoulof makes Francis Ford Coppola seem like an uncommitted dilettante. It makes sense that people want to reward him with unequivocal praise for this film. Unlike “Megalopolis” (2024), there is a good, cohesive film in here, but editor Andrew Bird seemed to prioritize the political and preserving historic social media content, which could have worked with a few adjustments to the story, which I’ll save for the spoiler section.

To an ignorant American, the opening is a bit of a mystery, and the moviegoer would not know where Iman works, what his job is, recognize the location that he visits before going home or instantly recognize the context if at all. This ignorance works in the narrative’s favor because we would not immediately take a stance on what kind of man Iman is, but the green light while praying is unsettling and more alien than a sign of spring and abundance. While Najmeh’s tender devotion to him in the form of late-night beverages and snacks is sweet, when she tucks him in like a baby, it feels wrong, but because of the cultural divide, judgment may be withheld longer. He spends more time at work than with his wife, who bears the brunt of raising the girls during a turbulent time. Iman claims to be a man of faith, but when his wife cosigns him as he considers violating his conscience to keep his job, it is a harbinger of things to come.

The two daughters, highschooler Sana (Setareh Maleki) and college student Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami), spend most of the time at home, playing with their smartphones and hanging out with their mom, who is either in the kitchen or perched in front of the television. The generational divide is expected as each person believes the media that they consume. Najmeh is on a respectability politics tear and does not even want them to have friends lest it jeopardize their father’s new position. As the protests get closer to home, Najmeh’s conservative rhetoric to her girls ramps up, but privately her resolve is shaken. She wants them to be obedient to keep them safe since they are just as much in danger from the government that she supports as dissidents who want to target them because of Iman’s position. Meanwhile Iman is getting acclimated to the office culture under the guidance of Ghaderi (Reza Akhlaghirad) and starts to bring it home.

If “The Seed of the Sacred Fig” has a problem, it can be too literal and is too long with a run time of 2 hours 48 minutes. Once Iman became an investigator who has the power to sign death sentences of people who are not guilty by his alleged personal standard of excellence, there is not much subtext to draw us in further. The family is obviously a symbol of how the state treats its people with the father as the infallible government, the mother as his faithful ally and supporter and the children as the dissidents. While I hate allegories, I did not hate this one because it was so obvious, and regardless of its flaws, any media that protests authoritarianism may need to obvious since people can be dumb. *Gestures widely around the vicinity of my glass house.*

Rasoulof’s opening scene seemed like a reference to “Zone of Interest” (2023), which depending on the availability of the film in Iran, may not be possible. As Stephen King (possibly) wrote in “Lisey’s Story,” we drink from the same stream. All the work scenes are disturbing as random people are facing walls as if the Blair Witch commanded them to, and rows of people are moved from one hall to the other. By the end of “The Seed of the Sacred Fig,” it is unclear whether Iman was ever a competent, principled man since his screen time is dominated with gaslighting and incompetence.

Rasoulof’s passion is admirable, but it is better to make a timeless film than a movie rooted in references which may not be recognizable in the future. For example, most people outside of Iran may be unfamiliar with Mahsa Amini. While the movie explains the situation through the dialogue as the mother and daughters debate which story to believe about the cause of Amini’s death, at the one hour twenty-minute mark, the narrative becomes transcendent because the movie finally shows what Iman’s work looks like outside of the office, and the effect that it has on people whom he claims to love. Rasoulof’s message is still clear but invites people to relate to the characters in real time unlike explicit political debates, which are easy to become desensitized to and ignore like white noise. It reminded me of a deceased friend, Jutta Gerendas, and her account of how her father, a high-level Nazi official, post-war abused his family, and their neighbors harassed each other. The antebellum Southerners cruelty to those they enslaved translated to violence directed at their neighbors and other white people because it is hard to compartmentalize bad behavior.

A long movie has more time to establish how the characters act. When the children and mother cook, they are thoughtful, prepare nutritious meals and eat together. When contrasted with how the father prepares a meal for them, the difference is stark. By their fruits, you shall know them. Throughout “The Seed of the Sacred Fig,” Najmeh is convinced that if Iman spends more time with the daughters, it will help, and Rasoulof shows how his presence has the opposite intended effect. Under Ghaderi’s guidance, a wedge grows between Iman as if his job duties should come before his family whereas before the promotion was supposed to improve the family’s life.

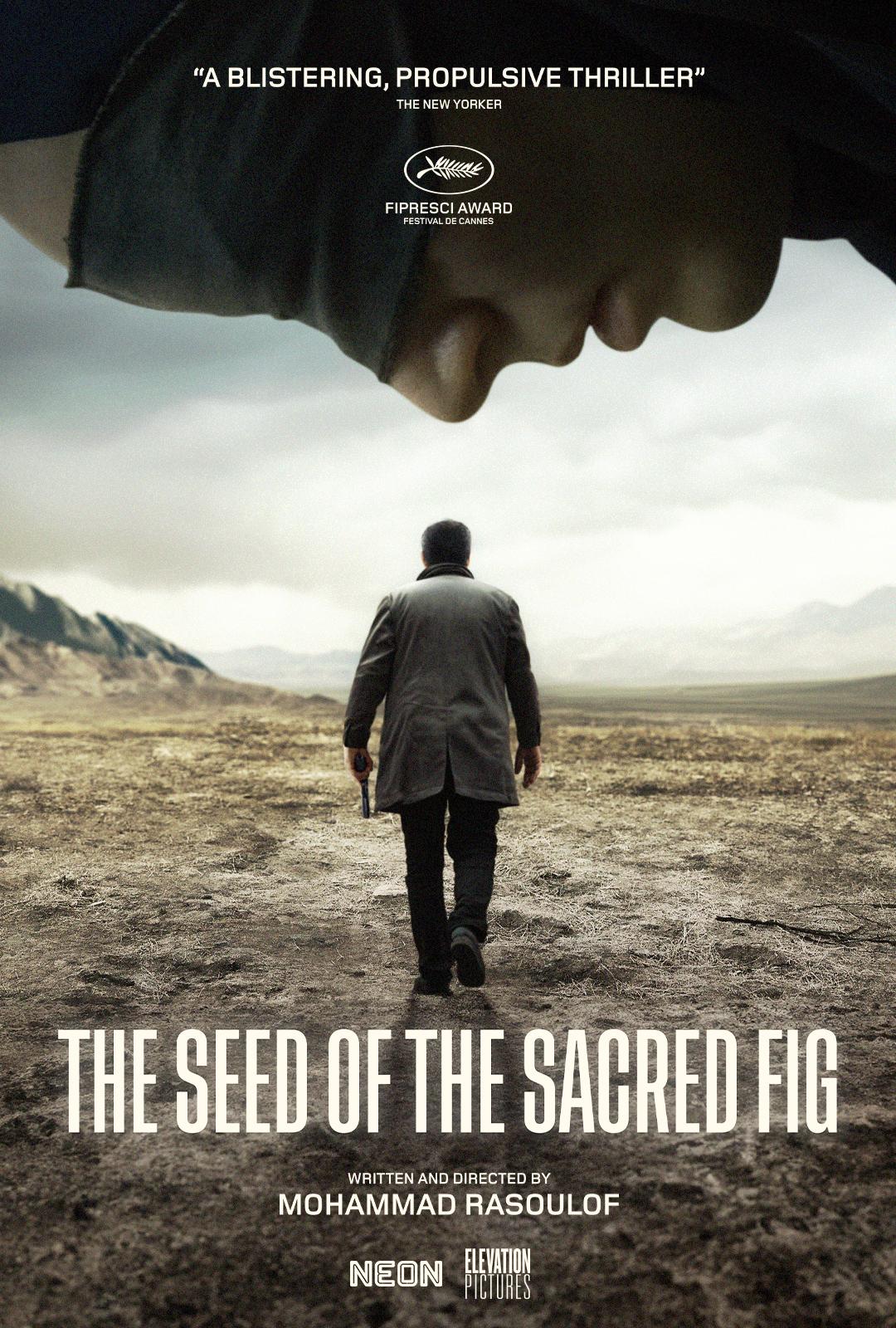

The denouement location is desolate, isolated, arid and abandoned, especially contrasted with the bustling capital. “The Seed of the Sacred Fig” could easily be a play since it is mostly confined to interior spaces, but that end makes it cinematic and would be impossible to convey in a stage production. It has a neo-Western feel, and it is worth hanging in there to see the nightmarish catharsis that Rasoulof was building up to.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

It was possible to cut a third of this movie, and it could still make its point. “The Seed of the Sacred Fig” should have been a horror movie because the end is basically “The Shining” set in an opposite type of environment. Horror movies should not be seen as trivial and are effective at viscerally conveying messages that a straightforward drama cannot. Eliminate Safeh’s storyline entirely or give it to one of the daughters with a less severe injury. I favor the prior. If the historic social media content was intercut with the daughters’ videos of their surroundings periodically then the return to the horror of video content would not be restricted to the sweet and sour contrast of the interrogation and home videos. It could have been like a found footage movie, but Rasoulof plays it straight, and it feels separate from the story even though it is arguably the reason that the movie exists. The home video footage feels real within the context of the movie in a way that the social media footage does not, but the news footage does. When the social media posts take up the entire screen, which is arguably supposed to be the daughters’ point of view, instead of remaining the size of the phone screen in their hands, the transitions are jarring because of the shifts in film quality, audio and style. The audience should view it as they would. Make everything normal until the missing gun. The family friend interrogation felt redundant considering the ending or at least too brief. Eliminate the ridiculous car chase scene, especially since it kind of makes no sense that the daughters would help the parents when they agree with the people filming them in protest.

I wish that no one took the gun, and that the father was too embarrassed to admit that he misplaced it. Then Sana should find it and keep the rest of the twists and turns, which are perfect. This section felt like a universal characteristic of oppressive, toxic behavior whether on a small or large scale. It is less easy for opponents to dismiss the film as naked propaganda in a scenario like that, which is a relatable concept: being blamed and tortured for someone else’s shortcomings and madness.