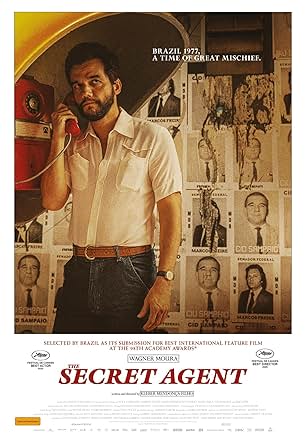

“The Secret Agent” (2025) is Brazil’s submission to the 2026 Oscars’ “Best International Feature” category, and the movie that PTA fans think “One Battle After Another” (2024) is. It also features Udo Kier’s last appearance. In the present day, a couple of transcribers listen to tape recordings made in 1977 about a researcher, Marcelo Alves (Wagner Moura), birth name Armando Solimões, a former professor at the Federal University of Pernambuco’s department of technology studies, trying to survive corrupt government police forces targeting him after crossing paths with an Italian descent industrialist, Henrique Ghirotti (Luciano Chirolli). Starting on Shrove Tuesday, February 22, before Easter and during Carnival, most of the film depicts life in Recife, the capital of the Brazilian state of Pernambuco located in the Northeastern region during the military dictatorship, which lasted from April 1, 1964 through March 15, 1985. This brilliant and challenging film reveals that life under a repressive regime may be brutal and violent, but it also shows how life remains deceptively normal, electric and fun before it turns on a dime. Writer and director Kleber Mendonça Filho’s powerful and surreal film takes big swings, many of which may not land, to illustrate how much gets lost and gained for lifetimes when dystopia strikes and expands beyond its explicit borders.

If you are expecting “The Secret Agent” to be like “I’m Still Here” (2024), disabuse yourself of that notion now. The narrative can seem circuitous and random making it almost impossible to discern which bits to hang on to and which to discard as flavoring. By the end, even though there are answers regarding what happened to Marcelo, there are still gaps regarding the details such as did he ever find paperwork regarding his mother, how did his wife, Fatima (Alice Carvalho), die, hat exactly did Ghirotti do at dinner that was so offensive. It is not just a story about people or a region, but the nature of history itself and that repressive systems enact violence on upright, ordinary citizens who just want to mind their business, which has ripple effects on the most basic information. It denies personal histories to families and on a broader scale, creates a huge hurdle to piece together a cohesive story for future citizens to know.

Regardless of which side the characters are on, angels, devils or somewhere in between, Moura and the entire ensemble cast never forget that a lot of life is incidental, not well planned, but it also turns on a dime. For English speaking audiences, particularly Americans, a lot may be lost in translation because of the different era, culture and region. For instance, India is slang for indigenous people of the Americas. The context clues should be sufficient so you will not be lost. A little before the midpoint of the film, the characters from 1977 and the transcribers offer explicit context in case you are lost. Mendonça Filho wisely decides to use the universal language of music and cinema as a nexus point. The image of sharks as a nightmarish figure versus the reality as a victim of human violence and extraction to dispose of bodies and expose venality is brilliantly coupled with Jaws and a Popeye cartoon playing on television. Also movies become a symbol of how we confront nightmares, which evaporates once seen. These nexus points are not just places of relief from oppression, but weapons against it.

OBAA’s image of revolution is fantastical and cartoonish whereas “The Secret Agent” is more realistic. Marcelo is just a hot nerd, family man and academic who is incidentally white passing, which causes more problems since people who benefit from the regime make assumptions about his sensibilities. His sin is having front row seats to an oligarch taking public funds from academia, which fortunately does not sound like anything that would happen in the US. Marcelo has a patent on lithium battery research. He finds refuge at a lively apartment building called the Ofir. One neighbor describes the residents as refugees in the same predicament which include a single mom dentist, a secretive Angolan couple, an implicitly gay, underage teenager and a party animal. Tânia Maria is Brazil’s answer to Kathryn Hunter, and she plays the only real revolutionary, Sebastiana, who is the unofficial mayor of the complex. While everyone eventually spills their secrets, Sebastiana only alludes to activities in World War II Italy with no details other than being a self-proclaimed anarchist and communist.

The legacy of fascism is far reaching on both sides with Ghirotti still holding the reins of power and infecting another country an ocean away, but this time in the Southern region in Rio de Janeiro. The war continues. It just changes locations. “To each his place” is a rule that they wield like a stick to require obedience to authority, but not a principle that they live by. If they do not want someone to work in their chosen profession, they expect people to fall in line without question. It is domestic abuse on a national to a global scale.

Kier’s final scenes are powerful. He plays a Jewish refugee who is admired because the corrupt local police believe that he is a Nazi in hiding, and nothing says dystopia like a government official taking the wrong lessons from history and still getting it wrong. Sound familiar? It is also so refreshing when filmmakers from countries that actually experienced repression depict the way that it functions. American filmmakers just slap a military uniform on the bad guy and call it a day. “The Secret Agent” connects how upper classes, local and state police, criminals and even journalists create a web to form a kakistocracy that only wreaks havoc and leaves a path of blood and death in its wake, including for them.

OBAA does have “The Secret Agent” beat in terms of visuals. There is no equivalent to the road scene here, but it does embody a Seventies aesthetic from wipe transitions, split screens, and fonts. When it shifts to the present day, no date needs to appear on screen. It is obvious based on the composition of the shot casually showing a smart phone or EarPods. The dip into horror tropes is not quite as successful as Mendonça Filho depicts local urban legends and folklore to amplify the unease of how the government is invading and inflicting violence. While disembodied body parts are a staple of horror, the world is not ready for a disembodied leg terrorizing night owls on the prowl and cruising. If he does not lose people at that point, then they are in for a treat.

The Hairy Leg was a journalist’s code for police brutality, which is also described in this film as “the mischief.” When a masked figure grabs Marcelo’s car, do not associate it with “The Wicker Man” (1973) or “Midsommar” (2019). La Ursa is a popular Carnival figure that symbolizes a bear hunt, which has European roots and is uniquely adapted to that region blending African and Brazilian traditions. The Bear causes chaos in the streets and begs for money, thus the association with the cops. If a beggar has the power to rip your face off, it is not begging. The only time that Mendonça Filho shows violence is when it is inflicted on these implicitly government sanctioned beggars, not their victims.

“The Secret Agent” is a film that you must trust and work with, but it is worthy of your time and effort. Even if you remain skeptical throughout the entire story, the denouement is surprisingly moving, powerful and solid despite the ambiguity inherent in the story. Moura deserves to get nominated for a ton of awards for an understated, resounding performance.