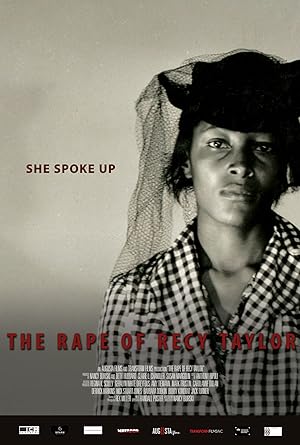

“The Rape of Recy Taylor” (2017) is a documentary that elaborates on Recy Taylor’s story, which was one of the first accounts featured in Danielle L. McGuire’s “At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance-a New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power.” The film tells her story and reveals how Taylor’s story galvanized black people nationally to become activists and organize, which sowed the seeds of the sixties Civil Rights Movement.

Nancy Buirski wrote and directed “The Rape of Recy Taylor,” which is consistent with her career as a documentarian. Buirski has devoted most of her films to telling American history with a special focus on racism: “The Loving Story” (2011) and “A Crime on the Bayou” (2020). She interviews Taylor’s family and a few historians, uses recordings of Recy Taylor telling her account and lands Cynthia Erivo to read Rosa Parks’ letters. She also assembles archival film—some that Zora Neale Hurston shot, creates montages of photographs and newspaper articles, and plays clips from race films to show black women from the past. Even in photos where they were relegated to the back of photographs as servants, Buirski zooms in on their faces and ignores the white families in the forefront. She tries to recreate the conditions of Taylor’s harrowing night with abstract images of trees in the dark, black women running on desolate streets and houses suddenly appearing in the distance. She centralizes the story of black women and tries to make her film’s depictions of black women reflect how they saw themselves in an environment that marginalized them. Buirski, a white woman, nails it in my opinion. It is a visual rebuttal to and photo negative of “The Birth of a Nation” (1915).

Buirski relies on editing, not a narrator, for viewers to decide the credibility of her interviewees. The juxtaposition of the Taylor family’s eyewitness accounts with a historical analysis from her nephew makes Larry Smith, a self-described amateur historian’s appearance, seem insensitive as he tries to lighten the questioning with an infidelity joke though he was not specifically referring to this incident. He later admits that he feels uncomfortable talking about it because he must live there, which reflects what has not changed. He uses language reminiscent from the sixties describing Northern agitators forcing Alabama to issue a formal apology.

While “The Rape of Recy Taylor” credits the outrage on Taylor’s behalf as a catalyst for nonviolent civil rights protests, the film spends more time on her family’s anger and subsequent physical response to systematic violence that the state condoned through Jim Crow and by only enforcing rules against violence if the perpetrator was black, even if it was defensive. For instance, Taylor’s sister later got jailed for responding in kind to an off-duty policeman slapping her. Taylor’s brother describes children’s hostile response to being segregated at the movies. The movie lingers on the descriptions of Taylor’s dad with the shotgun hoping to rescue his daughter. Her sister celebrates the alleged bad deaths of some of the rapists. While non-violence is a historical ideal, Buirski also honors and prioritizes the human one. She does not disapprove and frame it as criminal, delinquent or negative. The only regret is that Taylor’s dad did not become a vigilante and prioritized protecting his family.

“The Rape of Recy Taylor” is not an easy film to watch, but it brings Taylor to life in a way that shows her as a complete person in contrast to true crime, which sensationalizes the situation and creates the pleasure of tabloid. Buirski gives us an idea of Taylor’s life before the titular crime-an enthusiastic church goer, a sister, wife, and new mother. The last one made the event even worse than I originally imagined because no one should have to endure rape, but she may not have even been physically cleared for even consensual intercourse with one person. An additional devastation was the unanswered question of whether Taylor had wanted more children. After the rape, she could not according to her sister. Motivated to live for her child, it is easy to draw the connection that she remembered how much harder her childhood was when her mother died at a young age.

“The Rape of Recy Taylor” brings out more details that I did not recall from reading the book. Witnesses reported her abduction immediately to the sheriff, who was a direct descendant of the people who enslaved her family so he shared Taylor’s maiden name and was one of the rapists’ uncle. Also the seven rapists lived near her so while she may not have been the original target, it is not random. Without being explicit, Buirski paints an image of a terrifying neighborhood with enemies in every corner continuing the de facto legacy of slavery. After experiencing violent resistance from their first targets, the fact that the rapists deliberately stalked a black woman leaving church with other parishioners echoes contemporary hate crimes such as the 2015 Charleston church shooter.

“The Rape of Recy Taylor” does not delve into whether the rapists had harassed the Taylor family before or were jealous of them for some reason. There is only a reference to Taylor’s father telling his kids not to talk to the Wilsons, who ran a cab company and knew them. Likely out of respect, the film also did not explore why the Taylors ended their marriage though surviving a rape, a firebombing and constant harassment would test the strongest marriage. The film does not give us a sense of Willie Guy Taylor as a person or his extended family except that he was able to put out the fire and was with her as they moved at least two times.

“The Rape of Recy Taylor” unexpectedly shifted its focus to the perpetrators by having voice actors read their responses in police interrogations and interviewing a couple of family members. Unsurprisingly the youngest perpetrator is the only one who confirmed Taylor’s account with details about the shotgun, the blindfold and crying. Leamon Lee claimed that he had no idea why his brother was in trouble and described them as “good people with too much time on their hands,” and explained that “we had a good relationship with the blacks,” which makes one wonder his definition of bad. Unwittingly Lee describes how image rehabilitation works. Though underage, the rapists were hustled off to World War II and got to be recast as war heroes—no one gets cancelled. James York had a dimmer view of his brother and his brother’s friends as troublemakers but thinks that his brother changed because he married a Japanese woman. Let’s ask her and her family what kind of a husband and father he was though I understand that it may have seemed relatively revolutionary and countercultural in a segregated society.

“The Rape of Recy Taylor” is a beautiful movie that made me tear up. It is not graphic, but the subject matter is sensitive. If you want to learn more, I highly recommend that you read the book.