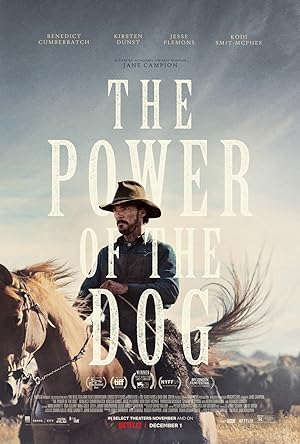

After a ten-year hiatus, Jane Campion returns to directing and adapts Thomas Savage’s novel of the same name, “The Power of the Dog” (2021), one of the best movies of 2021. In 1925, on a successful Montana ranch, Phil (Benedict Cumberbatch) torments anyone within earshot or under his gaze. Undeterred his brother, George (Jesse Plemons), disrupts Phil’s routine by engaging in a romantic relationship with widow Rose (Kirsten Dunst), who is not immune to Phil’s venom. Her son, Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee), endures the first attack. When Peter arrives at the brothers’ ranch, his new home, how will he navigate Phil’s scrutiny on unfamiliar ground?

“The Power of the Dog” is divided into five parts. The title is a reference to Psalm 22:20. Ordinarily a Bible verse would propel me into deep reflection stemming from it, but I am going to leave that to someone else. I wondered if Campion was revisiting the dynamic of families with a stepfather such as “The Piano” (1993) meets “There Will Be Blood” (2007), but this film is something else entirely. If I have a quibble with the movie, it is the voiceover in the beginning, which puts viewers on guard and retroactively explain what just unfolded, but it creates the initial impression that the story has a narrator, which it does not.

Campion shows and does not tell her story with evocative, majestic imagery. A viewer’s subconscious will pick up on the story’s trajectory long before their conscious mind does. “The Power of the Dog” will benefit from repeat viewings. There is casual male frontal nudity, but it is not gratuitous, and a brief trip to a whorehouse. Groups of men carousing in various states of dress provide the backdrop to the somber action in the forefront. Their joy is a marked contrast to their employers and expresses an implicit divide. The working stiffs have access to the casual pleasure of their bodies in a way that those with higher status do not regardless of their sexual orientation or marital status. There is a scene at the beginning of section five which appears as if a person with a tiny waist is wearing a huge dress with a long train, but it is really a shirtless cowboy in the shadows dragging rawhide from the barn into the sun. They can be naked and unashamed in an Edenic way that is unavailable to their employers, who feel diminished by their physical being or their undress reflects mental instability.

“The Power of the Dog” is absorbing with perfect pacing and stunning visuals. It takes its time to introduce elements of the story and establish the setting. There is no prose dump. The movie chooses a gradual revelation of each character’s psychological profile, and each character is a unique sea of contradictions that clash when encountering the other. Not since Lady Macbeth (2016) has a film shifted power dynamics by exploring gender, class, and sexuality in each scene. Even though the cast includes black actors, race is never explored, and the black characters are the equivalent of background scenery. Their characters have names, but do not play a substantial role.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

As soon as Peter started making that noise with his comb, I correctly predicted that he was Norman Bates’ ancestor. The soundtrack is dissonant when he initially appears. Think about it. His mom works at an inn. He is killing animals and dissecting them in his room. He killed his father, right? His daddy did not commit suicide. What did his daddy do to his mom? “The Power of the Dog” uses the trope of the treacherous gay man, i.e. any person who does not confirm to gender norms, as monstrous and untrustworthy. Phil is awful, and I am not excusing his behavior, but Peter killed Phil because he was mean to him and later rationalizes that he is protecting his mom. Only Phil’s horse has the right to kill Phil. Also casting Smit-McPhee is brilliant if you are familiar with his work. Peter feels like a natural conclusion after his character in “Young Ones” (2014). He also favors neo Westerns such as “Slow West” (2015).

“The Power of the Dog” is a terrific character study, starting with the brothers. Phil and George appear to be opposites with Phil being dominant and George being weaker, but as the movie unfolds, there seems to be a shift. The story is riveting for what is left unsaid. Before the movie starts, offscreen, was George already courting Rose? I believe so and believe it acts as the catalyst for Phil’s torrent of words from the beginning. Phil is vigilant in keeping tabs on George’s whereabouts during the first two sections of the film. He knows that George is seeing Rose and hates it. Is it jealousy or other factors mixed in? While Phil uses the cover of gratitude and solemn ritual, he lashes out at many living beings for simply being happy and not mourning as he is.

Phil is lean and talkative, obeys gender norms by being masculine, but is more dependent on his brother to play a certain role in his life that George had played up to that point, which we can only infer, not see. I am not suggesting anything incestuous, but I read Phil as a possibly autistic character who enjoys his routines and has very close relationships with few people so the loss of one feels devastating. Whether in a big house or away, they share a bedroom, and he cannot sleep without him even though it is natural that at some point, adult brothers should separate. Perhaps George was like the other employees, initially accepting that he existed as Phil’s audience for twenty-five years, or he knew the true nature of Phil’s relationship with Bronco Henry. In the second part, Phil tries to reminisce with George over their mom hiring hookers for them when they hit puberty, which is sexual abuse, but especially damaging once you realize that Phil’s only meaningful romantic relationship was with Bronco Henry, and he prefers the company of men. When Phil taunts Peter, it felt as if he knew that Peter was Rose’s son, and Rose was seeing his brother so it was the easiest way to attack her. Another possibility is that Phil is lashing out at a freedom that he does not have and is exercising his internalized homophobia, which he has done before with George by calling him fat and stupid, the latter being particularly cutting when other characters reveal that Phil went to Yale. In latter scenes, the presence of women demand that he change and act civilized, which he has deliberately rejected. He sees them as an invasion and keeps losing ground.

Phil loves ridiculing George, who does not adhere to masculine gender norms of the ranch, but of cultured society, which Phil rejected and escaped. Phil is not just railing against losing George, but the encroachment of a civilized society that he deliberately left because it was hostile to him even if they were not conscious of that hostility. Civilization wants him for his amusement, but not his true self. Phil finds freedom to be himself by rejecting refinement.

George is quiet, prefers to bathe indoors and use technology over getting his hands dirty, which undercuts his masculinity. George does not ask his brother for validation or consent at any point in “The Power of the Dog” though he is bothered that his employees do not listen to him. George is more independent in obeying his parents’ requests or using them as enforcers in comparison to Phil. George owns the house with Phil, but I asked myself why he could not build another house and live there, especially after he sees how miserable Rose was? Are these period conventions that would not be disrupted? While George seems like the better of the two, he is quietly dominant. He wants his life to look a certain way and initially seems to delight in Rose for who she is, imperfections and all. She is marrying up, but after her disaster with entertaining, he throws her to the wolves and expects her to survive while he vanishes. Phil does all the work, but George enjoys the fruit. We only see him work at the beginning of the film, which is also when he tries the bath for the first time. He wants a life without providing social lubrication to Rose or sacrificing his own comfort so Rose can be protected. He only confronts Phil when there are no spectators because then Phil will have the advantage with an audience, but it also means that Rose is unaware of George’s efforts. He also knows that he is forcing a life on Phil that Phil hates.

“The Power of the Dog” shows that George knows how to protect Rose and will do so if it does not put him at a disadvantage. George’s emblematic scene is when he becomes the dominant one in the room by adopting Peter’s role as waiter, including imitating the way that Peter performs it with the napkin draped over his arm. One of the privileges of being an affluent heterosexual male is the freedom to stray from gender and social norms without fearing that one’s secret will come out. Everyone whom he serves knows his identity, and that he is playing by serving them so he is immune to ridicule. He wants Rose so he is considerate, but he does not care about his servants. Like Phil, he does not inform their housekeeper that he is not eating at home and wastes their labor.

Eating at the inn is the beginning of a battle of wills between the brothers: the way that they try to command their employees, navigate rowdy diners, treat Rose and the paper flowers, a symbol of Rose for Peter, who is honoring her former career as a florist. The men who work on the ranch listen to Phil, not George, because he works with them and adheres to their traditional gender norms. The men see Phil as mysterious and a fount of knowledge, the source of their livelihood. Phil can see something in the landscape that no one else can. In contrast, “The Power of the Dog” starts optimistically with Rose and George standing side by side to appreciate the grandeur of the landscape. Based on George as waiter role, Rose is confident that George will keep his vow to protect her. They are adorable as George introduces her to the bathroom. Dunst and Plemons are a real-life couple.

One of the earlier tragedies in “The Power of the Dog” is that music is a point of contention, not common ground, for Rose and Phil. They love music, but Phil hates the pianola and Rose practicing on the baby grand. Rose makes mistakes with music. She regrets putting the pianola out for guests to use. When George encourages her to get comfortable in her new home, she closes every door to be alone. Campion can do horror. Phil appears at the edges of the frame, goes up the stairs in his trademark way (2 steps at a time) without his spurs making noise and Rose is oblivious until she hears the front door creaking open. During this sequence, the camera is slowly panning left as if it is sneaking up on her. She realizes that Phil is home. He opens the door, starts making noise with his spurs and plays the banjo whenever she resumes playing until she stops, and he shows off his skill. He dominates the frame from up above—the camera is tilted up at him and cuts to staring down at her. Phil’s message is clear—I’m better than you will ever be.

Phil’s absence and Rose’s presence at the governor’s dinner make them perfect foils. Phil refuses to be entertainment or change, but is desired and sufficient. He can stand alone, apart, untouched, single, unchanged and articulate his pride in his life. Rose is married, but alone. She feels inadequate, is unable to make conversation and freezes at the prospect of singing for her supper. Imagine a world where Phil does not see Rose as the enemy. They could bond over music, and he could reassure her that she has nothing to prove to anyone, but he sees her as an enemy, the reason for civilization’s invasion, and an annoyance so he shines a spotlight on Rose’s inadequacy. Even though the governor and his wife and the brothers’ parents do not necessarily know that Phil is different or gay, Phil, who is the head of the business and household, is treated on the same level as Rose, a woman, the newest member of the family and a wife. To this day, there is a phenomenon of accepting minorities whether they are people of color, women or members of the LGBTQ+ community as having a seat at the table if they only act as entertainment. Phil has more privilege as a wealthy man to reject this attempt at taming then he wields it against Rose. Rose feels more at home with the servants, women, not the ladies with political or financial status.

Old Lady (Frances Conroy) is the only one who can stop his attack and attempts to tame him until the governor, who acts as the social lubricant, stops and signals to everyone to exit. She is well read, and Phil probably takes after her, but they are also engaged in a stalemate. She is disappointed in his rejection of civilization. Phil’s resentment of Rose stems from her identity as a mother. Phil later would admonish Peter, and Peter tells Rose that a man must separate from his mother though their relationships with their mothers seem to be different.

While I am sympathetic to Rose and am annoyed that her married family fails her, I am also exasperated that a single mother in the Wild West needs protecting. Peter is also a victim of abuse since he is parentified and feels that he must protect his mother, who is an adult. When Phil ridicules Peter, Rose does not defend her son though she does retrieve the other paper flowers. Campion uses a lot of close ups of Phil’s hands, and it starts in this scene. Phil fingers Peter’s rose. Homoerotic, much? Then he burns it. Later when Phil starts being friendly to Peter, the way that he creates the rope makes the rope seem like a phallic symbol. As Phil removes Peter from his mother’s sphere of influence, Rose is concerned as if Phil is going to abuse Peter, but she does nothing to intervene. She is less concerned that Peter is going to be hurt than she is going to lose her only person.

I never believed that Phil was going to sway Peter. Before Peter goes to the ranch and witnesses Phil’s psychological abuse of Rose, while shopping with Rose, he explicitly chides Rose, “I don’t want him to meet a certain person.” He has a “friend,” and if he is concerned about that friend meeting Phil, maybe that friend is like Peter. He hates Phil after that first encounter. Prior to capturing Phil’s attention, we see Peter trap a rabbit. The way that he approaches his mother with the sack feels sinister. He looms over her in bed. It is a relief to discover that it is a rabbit. Even Rose thinks that it is a snake. Peter is deliberate in his movements. Lola (Thomasin McKenzie), the younger housekeeper, is the first person to consciously recognize that Peter is dangerous. Phil is waging psychological warfare on Rose to kill her, but Peter is homicidal. After he discovers Phil’s secret place, he captures Phil’s attention and everyone else’s by making a great show of walking up to a tree, looking at birds then walking back. The ranch hands catcall Peter, not his mother, but Phil is silent. Whereas before Phil encouraged the ridicule, this time, Phil stops it by calling Peter over to offer him the gift of a rope and his version of an apology.

There is ambiguity regarding Phil’s reason for taking an interest in Peter. An older man behind Phil says “No one tell him to soak those jeans.” Perhaps Phil finally feels empathy for once being like Peter and someone showing him the ropes. Peter replies, “You want me, Mr. Burbank,” which has a double meaning and is a possibility considering the way that Phil makes the rope. Peter is looming over Phil during this exchange and has a hidden agenda. Even though Phil has more experience and knowledge, Peter is operating from an advantage. Another possibility happens soon thereafter when Phil notices how Rose reacts to Phil making friendly overtures to Peter. Phil realizes that he can further wound Rose by taking away Peter just as she took away George from him. It is possible that George taught Phil that it was possible not to accept being alone.

Later Phil treats Peter like one of his men and whistles him over. Phil closes the barn doors so Rose cannot see Phil and Peter talking. Rose’s condition deteriorates further, and Peter starts making that sound with his comb when he consoles her. I didn’t understand why Rose keeps saying to Peter, “We’re not unreachable,” while caressing Peter. Peter replies, “Mother, you don’t have to do this.” Do what? “I’ll see you don’t have to do it.” At that point, Peter is explicitly saying that he is going to kill Phil. The next scene shows him furiously turning pages in his medical textbook, and if you look at the illustrations, it explains Phil’s later appearance. Also Peter fakes being worse at riding a horse for Phil and the cowboys’ amusement than he actually is because after he falls off the horse, in the next scene, he expertly rides a horse down a steep hill to cut the hide off a deceased cow.

When Peter and Phil go on a trip together and share a common interest of messing with bunnies, Phil is taken aback at how Peter soothes then kills the bunny. Phil, like the bunny, gets a wound in his hand, which Peter notices and points out. We see the parallels, but Phil does not. Phil rejects his education as confining and cosplays being rougher than he was, but Peter embraces his education and does not change as he matures. He rejects that he needs a man to mentor him. He can educate himself.

As Phil tries to drive a wedge between Peter and Rose, unaware that he is hardening Peter’s resolve to destroy him, Phil offers his personal mission statement that Bronco Henry gave him, “A man was made by patience and the odds against him.” It explains how Phil is operating in his campaign against Rose. Peter counters, “My father said obstacles, and you have to try and remove them.” It explains that Peter sees Phil (and implicitly his father) as an obstacle that he decides to remove. Peter reveals that his father was an alcoholic. “He used to worry I wasn’t kind of enough. That I was too strong.” Phil scoffs because he only has one definition of strong, which is his Achilles heel, but he also tries to be encouraging. Phil’s pride in pain, eschewing gloves but constantly cutting his hand, ends up being his downfall.

If “The Power of the Dog” confuses me, it is why Phil made a regular practice of burning the hides. I understand why Phil wanted them this time, to make the rope for Peter, but why was it a tradition? How does the ranch make money? Even though Rose and Peter were not acting in concert, the common use of gloves to get Phil to use the rawhide is similar. Rose lashes out at Phil for taking away Peter by exchanging his hides. Peter gives Phil hope by saying that he wants to be like Phil and mimicked making the hides. Peter is suggesting that Phil is his Bronco Henry. Phil is naïve, which is ironic considering that he accused George of being the same with Rose, and Peter is seducing him. Peter is what Phil thought Rose was. As Phil’s health deteriorates, Rose recovers fully from passing out the day before. It is Phil stumbling around outside, which Rose did before. Peter sees through the window and makes no attempt to accept the rope as a final request from Phil. It is a humbling moment for a man who strode with purpose as cattle and men parted to make a path for him.

In death, Phil completely loses the battle in death as he is bathed and shaved to be acceptable to the public. His dog is now a pet companion for Peter, who has the run of the house, which was as Phil initially feared. Peter wins and observes Rose and George kissing after the funeral. The treacherous gay man trope trumps the tragic gay man so a heterosexual couple can be happy and survive. Heteronormativity must be the priority of every character or be punished. Savage was a gay man so I am not suggesting that he is trying to promulgate these ideas, but they are in the ether. Everyone blames Phil for their problems, but excuses George because he is nice although he (understandably) shuts out Phil and vanishes when Rose needs him the most. Phil and Rose could have commiserated over the ways that they felt abandoned by George, but instead they blame each other for feeling isolated when they look for George and cannot find him. The heterosexual man suffers zero consequences for bringing these two together. George better be careful because Peter will keep an eye on him. Please burn that rope before someone touches it and gets infected.