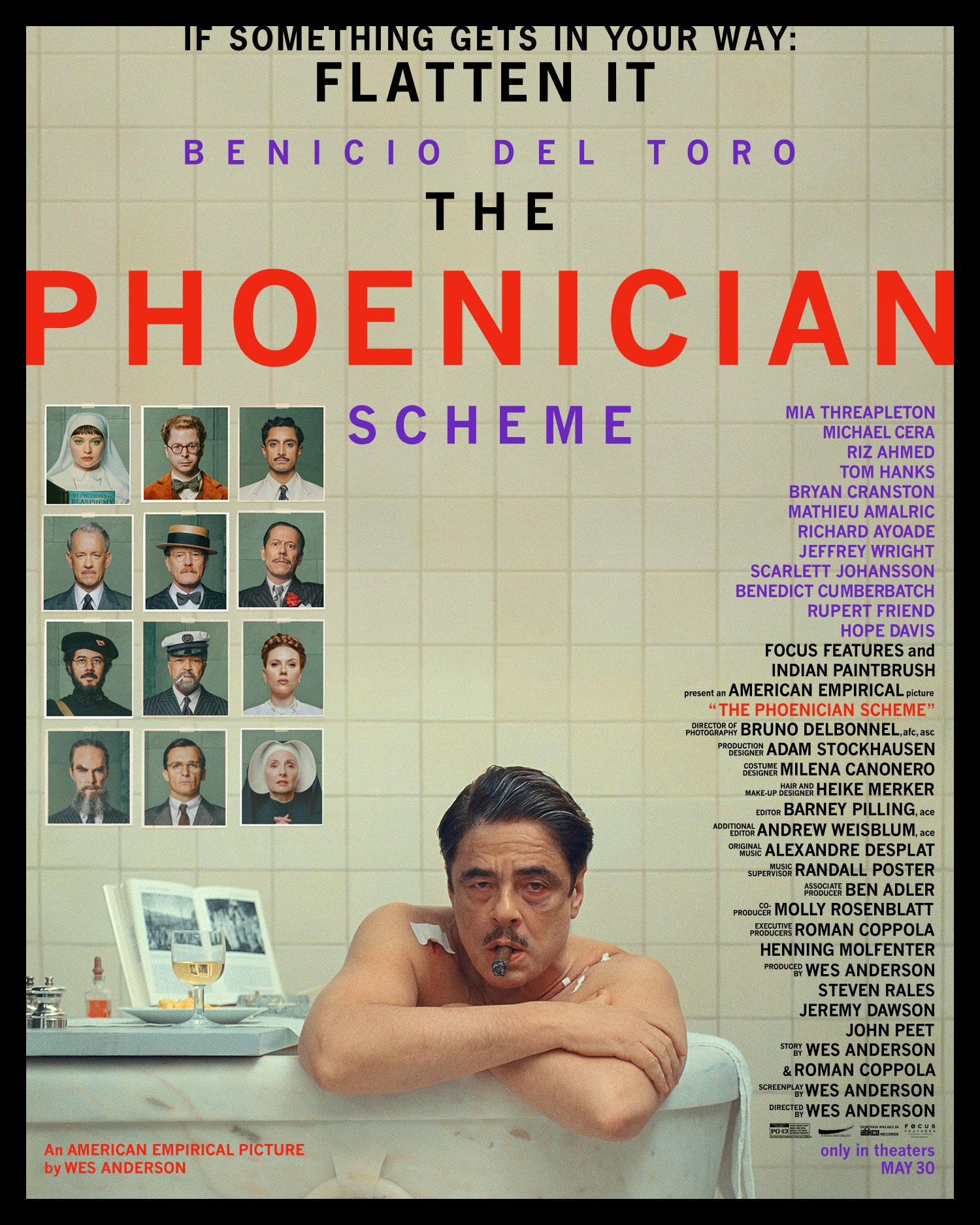

“The Phoenician Scheme” (2025) is Wes Anderson’s latest film and his most inscrutable and ambitious film to date as it tackles generational curses, God, international business, and global government conspiracies. It is also an elaborate struggle over the earthly soul of Zsa-zsa Korda (Benicio Del Toro). The film opens in 1950 with another assassination attempt and a quick peak at the afterlife, which motivates Korda to ensure that his life’s work will live on through his daughter, nun novitiate Liesl (Mia Threapleton). Liesl has other ideas. Will they find a way to complete the most important projects of their lives?

“The Phoenician Scheme” is not the kind of movie that you will get on the first try. The narrative structure, the visual composition, the massive A-list cast and the details will overwhelm you and make it difficult to walk away with a clear sense of what you saw. For most moviegoers, it will not be an obstacle because it is sufficient that Anderson directed and cowrote the script with Roman Coppola. They would watch a television reality show if Anderson ever deigned to create one. The rest of the audience is there to catch a glimpse of Michael Cera, Willem Dafoe, F. Murray Abraham, Tom Hanks, Bryan Cranston, Scarlett Johansson, Benedict Cumberbatch and Hope Davis with little care about what role they play but just enjoy them in unfamiliar and unexpected situations while being recognizable. The deep cut cinephiles will also be in attendance for Jeffrey Wright, Steve Park, Mathieu Amalric, Richard Ayoade, Rupert Friend, Riz Ahmed, and Charlotte Gainsbourg. Most viewers will laugh out loud and enjoy the absurdities of their accents, activities and plans. It is almost as if Anderson channeled a hypothetical version of Yorgos Lanthimos filming a live action cartoon with none of the Greek director’s signature menace and foreboding.

Instead, the stars of “The Phoenician Scheme” are less famous though no less impressive than their supporting cast. Long before he appeared in “The Usual Suspects” (1995), Del Toro has been around for over a decade, but rarely as a protagonist and mostly as a character actor despite his distinct appearance. Though Threapleton has been around for awhile, mostly in television series, she is not well known so this will be her big break. This first lead performance will remind some of the second coming of Mia Wasikowska, not Threapleton’s mother, Kate Winslet. (Her dad is Jim Threapleton, a painter and filmmaker, and his most famous work is as third assistant director in the 1999 version of “The Mummy.”) They are strong actors with distinctive features, but not so well known that they distract from their roles as the Korda parent and child.

The Korda family are cutthroat competitors going back at least three generations with their success rooted in blood, which means at best, they live separate lives, and at worst, they try to kill each other. After having black and white visions of the afterlife, often on trial for his life, Zsa-zsa decides to reignite his relationship with his daughter using business as the excuse. She is the only one who calls him on his odd quotidian practices. The movie is a dance between them with him gradually becoming less secular and ruthless, and Liesl becoming more worldly and enjoying the pleasure of being a physical being.

“The Phoenician Scheme” is divided into several segments: the introduction, the overall thirty-year plan for the Korda Land and Sea Infrastructure scheme, then delves into the building blocks of that scheme, which become chapters in the narrative and includes the Trans Mountain Locomotive Tunnel, Marseille Bob and the Marseille Syndicate, the Trans Desert Inland Waterway, Cousin Hilda and Utopia Outpost, Emergency Directive, Uncle Nubar and the Reliquary. The epilogue is a surprise. The scheme starts to fall apart when a board of countries, with the CIA in the lead, decide to conspire against Zsa-zsa’s business plans, which creates a financial gap between the amount that different players offered to put up (a fair share of 25% each) and the actual price. There is a plethora of gaps that this financial complication only highlights: spiritual, emotional and literal distance gaps between goal and reality.

The father-daughter journey is about bridging that gap but also exposes that Zsa-zsa prioritizes business over relationships when it comes to money. The story is an ambitious gambit at achieving what “Star Wars: Episode VIII – The Last Jedi” (2017) achieved: showing how government, legitimate business, underground, illicit business, religion and rebels are simultaneously at odds and in bed together. While Zsa-zsa is not trustworthy, he has enough grace and human qualities to reingratiate himself with his business partners but does too much damage to return to their original position. It also simultaneously functions in the same manner that “Asteroid City” (2023) does. All the hurly burly matters less than trusting the cast and their execution to carry you to the end even if you do not understand everything. Often the sets and composition are staged like a play such as when Liesl in bed with curtains.

Usually, by deliberately making the story mechanics confusing, using monotone delivery and rigid visual style, Anderson’s stab at Brechtian narrative techniques is successful so the audience can never forget that they are watching movie and instead focus on the underlying emotion. “The Phoenician Scheme” does not quite stick the landing and could leave some moviegoers snoring in their seats after having nothing to anchor them. The good news is that a second round should fix that problem, but how many people will be able to give the film a second chance if sleep was more alluring? Despite a blessedly short runtime, the message is unclear because too much is going on.

“The Phoenician Scheme” delivers an optimistic and naïve message: finding the balance between ideals and amoral, aggressive competition. In the end, the CIA and its world partners are like God-omnipotent, omniscient and ultimately benevolent. Right before Korda meets the board, he feels important to discover that he is the target of the board’s conspiracy, but in a heartfelt way. The final image of success for the Korda family will be a surprise unless you paid attention to Zsa-zsa’s stories of his childhood. World peace and prosperity rests on the shoulders of one family, and the best part is that family is ephemeral, not blood. There is the question of Lena’s paternity, which does not change anything in a poignant manner, and Nubar having “all the blood,” but not being human or acting like Zsa-zsa’s brother. The father and daughter relationship is rooted in spirit, and like Proverbs 27:17, “As iron sharpens iron, so one man sharpens another.”

If you are unfamiliar with Anderson and not just interested in the vibe and spectacle, “The Phoenician Scheme” may not be the easiest film to get started. If you are familiar, it still may not be your cup of tea, but if you are prepared to watch it more than once, it will be easier to appreciate the work as more than just meaningless nonsense. If you are just into movies as a visual media, you will be a happy camper because Anderson is in fine form. Matthew 19:23-26 reads, “It is easier for a camel to go through a needle’s eye, than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.” It is even easier if the rich man cannot die like Korda. Anderson solves the problem by showing how to achieve heaven on earth…for characters in a movie.