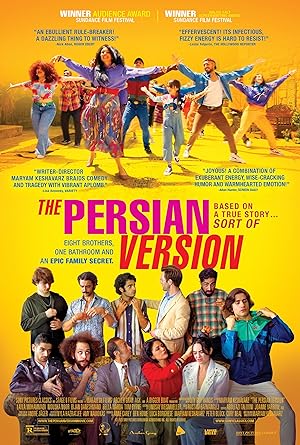

“The Persian Version” (2023) covers a pivotal thirty-eight weeks in the life of a successful Iranian American writer and filmmaker Leila (Layla Mohammadi). Leila breaks the fourth wall and contemplates her failed marriage to Elena (Mia Foo) and strained relationship with her mother, Shireen (Niousha Noor). Iranian American writer and director Maryam Keshavarz delivers an upbeat, poignant, genre defying dramedy.

Leila is the narrator and main protagonist who feels divided between her cultures, constrained within her ambitious, rule-breaking identity and exiled from her family. Leila’s story jumps between time periods and countries—Iran and the US—to fill viewers in on her life and family history with special focus on the women in the family. The film starts on Halloween as she crosses the Brooklyn Bridge heading to a costume party and ends on the wedding day of one of her eight brothers. Near the beginning, Shireen rushes Leila’s father, Ali (Bijan Daneshmand), a former doctor, to the hospital to get a heart transplant and treats Leila differently from her brothers, who get to visit their father’s bedside. Shireen leaves Leila in charge of caring for Mamanjoon (Bella Warda), her maternal grandmother, who encourages Leila to think of her mother as one of her characters so she can better understand her. The thought exercise leads Leila to recall a fateful Thanksgiving when her mother first exiled her from the family and leads her on a hunt to discover the real reason that her parents emigrated to the US.

If you are not into subtitles, “The Persian Version” may be difficult to follow but is worth the effort. Because the narrative is not linear, it is possible you may not be able to keep up with the fast-paced editing, alternating timelines and shifting central characters, but Keshavarz delivers enough jokes, captions, and dialogue to orient the average viewer. If the narrative was linear, it would span from the 1960s to 2000s, and Keshavarz leverages nostalgia for the era, particular the 1980s with needle drops that lead to colorful wardrobe, big hair, and choreography to the tune of Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun.” Leila is an attractive, engaging and likeable protagonist, and when the film starts, Shireen will seem as infuriating to the viewer as she is to Leila, but Keshavarz, through Leila’s exploration of her mother, shifts that favor for Shireen after a half hour when Leila recalls her mother’s reaction to her father’s first heart attack.

“The Persian Version” soon becomes Shireen’s movie, who finds inventive ways to clean up Ali’s messes and emerges as a captivating, dynamic character in her own right, an enterprising immigrant businesswoman who uses microaggressions for inspiration. Leila only suffers in comparison to her mom, who becomes a capitalist activist and finds success by courting immigrant clientele and helping them discover their own American dream. Watching an Iranian woman do business with Korean and Indian families is a rush, and upon rewatch, the movie reveals how Shireen made her indelible mark on the streets that Leila would later walk on (hint: look for the Patel Brothers’ storefront and transforming sign).

Shireen’s story parallels Leila’s as flashbacks reveal shared experiences: romantic heartbreak, love of music and dancing, seeds of hope in and fear over the health of unborn daughters, education and career ambitions and using the streets of New York and Brooklyn Bridge as their key to meditation. After thirty-three minutes, Shireen’s sexist treatment and parentification of Leila are still inexcusable, but understandable. While stern, Shireen only reveals her vulnerability to her daughter, and Leila begins to see herself through her mom’s eyes and understand how her resistance and insensitivity to helping her mom added to Shireen feeling overwhelmed. Other characters like Mamanjoon and Ali get reframed and seem less like the good guys in comparison. Mamanjoon unintentionally passes on family trauma to Shireen who later equates Leila’s lack of a traditional marriage with a brother’s drug problems.

Leila identifies as lesbian, but her only successful onscreen relationship is with a cis gender man, an actor who often dresses as his Broadway character, Hedwig (Tom Byrne). This relationship does not take up as much screen time as the family dynamic but continues a cinematic trend where an onscreen queer person ends up engaging in happy heterosexual relationships instead of depicting successful same sex couples. Based on the similarities between Leila and Keshavarz, who identifies as bisexual, Keshavarz was not engaging in cynical marketing but used an aspect of her life for narrative inspiration. Leila and thirteen-year-old Shireen face accusations of being selfish for choosing career over marriage and children so sign a waiver for allowing heteronormativity and realism over internalized misogyny.

“The Persian Version” may suffer from colorism in casting the young sixties era Shireen with Kamand Shafieisabet, who does not resemble Noor and seems shades lighter. On the other hand, people get darker as they get older, and Shafieisabet carries around 25 minutes of the movie in an extended, no-frills flashback which reveals why Leila’s parents immigrated to Iran. Keshavarz changes the entire tone of the movie by departing from Leila’s style and making Mamanjoon then the young Shireen into narrators. Mamanjoon’s story sounds like a twist on a gunslinging Western as she confronts Ali at the beginning of their marriage. There is a brilliant sequence when the sixties-era Mamanjoon walks down the street and imagines that the townsfolks are speaking her furious thoughts instead of having unrelated conversations.

The flashback imagined version of young Shireen interrupts the proceedings. Part of immigrating means having the right to tell your own story, and Keshavarz imagines giving that privilege to Shireen although within the movie, Shireen never actually confides her story to anyone. It is still Leila’s imagination of Shireen’s story, but is told as a straight, drama autobiographical story. Shireen embeds the plight of Mahdis (Mahdieh Maleki), her as motivation for Shireen’s choices and Ali’s childhood to explain his missteps. “The Persian Version” is such an empathetic film that it refuses to make anyone a villain even though an adult marrying a young teenager then making her life more difficult are considerable obstacles to eliciting anyone else’s sympathies.

While I normally prefer for a story to be told in a linear fashion, by waiting until closer to the denouement to reveal Shireen’s origin story, it infuses the denouement with more poignancy. Viewers may not notice the similar parallels if these parts of Shireen and Leila’s life were not adjacent to each other or explain why the birth of Leila’s first child may motivate Shireen to make up with Leila and reveal her emotions. Contrasting the circumstances leads to the most memorable tableaus throughout “The Persian Version.” The birth of her first grandchild, especially because of its gender, dislodges the stubborn silence between them.

If “The Persian Version” has one flaw that sticks, Keshavarz only depicts Leila’s family and romantic relationships, not her friendships, which are implied, whereas Shireen seems to have fiercer friendships with women throughout her lifetime. This omission is the only blemish in a film that otherwise captures the exuberance and resilience of Iranian women.

The most relatable aspect of The Persian Version” is when Mamanjoon cautions Leila, and possibly all the American viewers, “In the West, you live to work. You are your work. What about joy. Remember to live amongst those ambitions.”