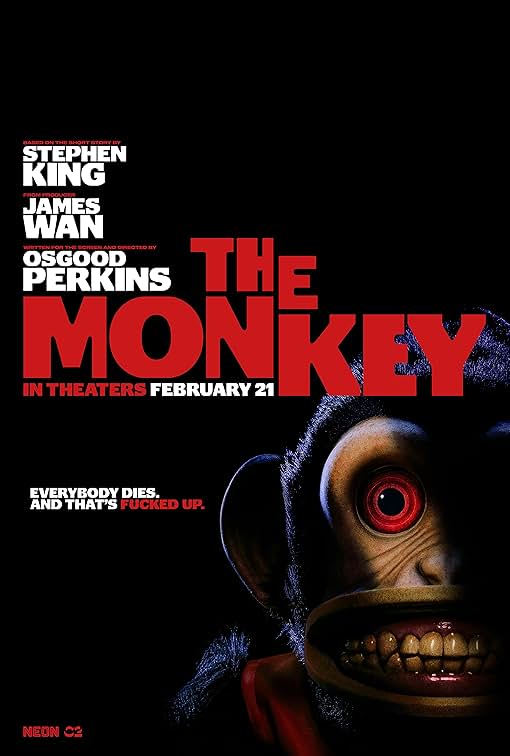

“The Monkey” (2025) is the second film adaptation of the Stephen King 1980 short story, which originally appeared in “Gallery” magazine then was revised and published in a 1985 King short story anthology called “Skeleton Crew.” Writer and director Osgood Perkins uses the concept of a “bad magic killer monkey” as the inspiration for his horror, dark comedy, which takes delightful liberties with the original. Starting at an unknown point in the cold opening, then 1999 and resuming in 2024, the males in the Shelborn family seem to be connected to the titular simian and cannot get rid of it. As the deaths mount, twins Hal and Bill (Christian Convery as children and Theo James as adults) are so affected, that it haunts them as men even when no one is dying. Will they ever face the music and dance?

Adult Hal narrates most of “The Monkey” though Bill takes over for a brief interval before the final act. Though they are twins, they are opposites and enemies. Bill is a bully who loves picking on his brother, is already interested in girls and seems to lack empathy. Hal wears glasses is a smidge smarter and has more impulse control but is just a kid and is tired of bearing the brunt of his brother’s meanness. Their father (Adam Scott) hit the road a long time ago leaving their dance instructor mom, Lois (Tatiana Maslany), with the responsibility of raising the kids and dating as if it is a joyless requirement. During one of her reflective moments, she tells them that one day they will inherit the belongings (baggage) that their father left behind. The kids do not wait for Mom to kick the bucket before rifling through his things when they find a Tiffany blue hat box containing a monkey armed with drumsticks, a drum, and a key in the back that can be turned so it can bang away. Despite Hal’s reservations, Bill turns the key, which leads to a series of Rube Goldbergian, brutal deaths that look like freak accidents. The trauma is so devastating that they think that they are cursed, which leads to how does they live without hurting others if they are. They take opposite paths but wind up in the same place.

Perkins discovered his formula on how to make a funny, gorrific movie with buckets of blood. Adults talk in a stylized, melodramatic fashion but with a monotone, dry delivery about topics inappropriate for a child. This dialogue is supposed to be comforting within the movie’s universe like a bedtime story, but to the audience, has the opposite effect as if everyone is telling a terrifying story around the campfire then decides to resume normal life with gaiety or as if nothing happened. The adults are not adulting, i.e. no one is acting appropriately. Priests curse. Moms are clueless. Bosses are informal. No one knows what they are doing, but the kids seem to have more of a clue at least what is going on.

“The Monkey” is about the fear of fathers passing down something awful to their sons when they grow up and the inexplicable guilt of existence or surviving like a walking fatal disease vector. It initially seems as if it could be an irrational superstition, but it is a King story so of course it is supernatural. This tool of havoc seems to only attract fatherless males, but unlike society, Perkins leaves this issue squarely on the guys’ doorstep as a father’s legacy. Hal is vulnerable first because he is bullied. Bill only becomes aware of the threat after he loses someone whom he loves and feels pain for the first time. Later Ricky (Rohan Campbell, who resembles Iwan Rheon), a young man with jet black hair always over his eyes like a shaggy dog, is drawn to it and reminds him of his dad. The monkey evokes the desire to use it like a weapon, to discard it or to worship it.

Even though “Longlegs” (2024) got all the accolades, “The Monkey” is a far superior film and is the horror movie to beat in 2025. February is early to bestow that ranking, but it is a perfect movie that seems to fix all the story problems that Perkins encountered in “Longlegs,” which was more style than substance with a narrative that went off the rails and not in a good way. “The Monkey” is so good that if paired with “Longlegs,” it resolves unanswered questions or elaborates on plot points that seemed to drop from the clear blue sky. The devil does not have to be literal. At the eleventh hour, Hal calls it the devil, which seems to be Perkins’ moniker for inexplicable phenomenon that causes harm even though it is not necessarily evil. After all, everyone dies. Hal blames himself for using this object as a weapon that hits the wrong person, but when someone asks him if he ever killed anyone, he answers no. The organ grinder monkey is not a toy because it can kill, but a child using it is not a murderer. Hal hearing his answer heals himself. If he is not a murderer, then maybe he cannot destroy other people just by being in their lives. It offers the possibility of love.

While “The Monkey” is not as funny the second time around, repeat viewings make it easier to appreciate how well-crafted it is. A lot of the gruesome deaths or supernatural figures are foretold in earlier casual lines of dialogue. The Babysitter Annie (Danica Dreyer) has a last name: Wilkes, which feels like a shoutout to “Misery.” As adults, the protagonists only live in motels, which feels like a reference to “Psycho” (1960), which Perkins’ father, Anthony, starred in. James’ voice as Bill calling Hal feels like a “Scream” franchise reference.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Captain Petey Shelborn, the twins’ father, is only shown once in the opening. Did he leave because he is a bad dad or was he like Hal and wanted to keep away from them because he was trying to protect them? There is this implicit lesson in “The Monkey” that it is better to have an imperfect, cursed biological father than a theoretical expert like Ted (Elijah Wood), the stepfather to Hal’s son, who is also named Petey (Colin O’Brien). It is not until Bill and Petey meet that Bill reveals his father’s name. Though Bill never knew Petey, he wants Hal’s Petey to come to him as if he is the second coming of their father and make sure that he lives.

Petey is like the monkey—someone associated with a father figure. When it reappears, Perkins dissolves from son Petey lying on his side to the monkey in its first appearance as an adult. It chooses when to appear, and it does before Petey loses his father. Randomly one of my favorite shots is when the boys meet the monkey for the first time and a boomerang is in the background because the monkey functions like one. When it gets thrown away, it returns to the person that threw it. Relationships are not disposable even if “our very best may be pretty bad.” They can only be managed. It felt as if there were different monkeys used because its facial expressions seem to change.

It is totally feasible that despite being a mess, Hal would have a child because James is hot, and even real estate agent Barbara Bittsmiddleton (Tess Degenstein) mentions it. It is interesting how Hal overtakes Bill even though Bill had a lead start. In the end, Bill is no longer interested in living but is frozen in the death of his mother.

The costume design of Bill’s adult outfit is wonderfully detailed and almost like an autobiography. The cummerbund is cut from the cloth of the shirt that Bill was wearing when he witnessed his mother dying, and it is the same suit that he wore to every funeral as a child. The funeral suit feels like a reference to “Reservoir Dogs” (1992). Unlike Hal, he is suffering from arrested development, stunted from trauma and living in the past, and when Perkins initially shows adult Bill, he shoots him in the same position as Longlegs (Nicholas Cage) when he is revealed in the basement. While the monkey does not grant wishes, it does kill Bill in the way that Hal fantasized as a child before the twins knew about the monkey, with Lois’ bowling ball to his face.

The end is the apocalypse, and the Pale Rider, Death appears, which Hal references when he discusses his visitation time with his son to his boss, Dwayne (Zia Newton). Hal is comparing himself to Death in this joke, which is the relationship that he believes that he has with his son whereas his son believes that he does not want him. The real horror is when estrangement is rooted in a toxic, self-condemning mindset that isn’t true. Sure, the monkey is killing everyone, but now that they know that, they can be together because there is nothing that they can do to stop it. They will die eventually, but not the day that the Pale Rider passes them just as he did every time they have multiple near misses, which is not noticed or celebrated in the same way that the sensational deaths are noted. The real curse is fear, and it is the only thing that “The Monkey” shows. Hal gets choked up when he talks about Aunt Ida. It is easy to forget or not show the good moments, but it does not mean that they do not exist. Bodies do not just die. They dance.