The Look of Silence is a sequel to Joshua Oppenheimer’s first documentary, The Act of Killing, which focused on the genocide perpetrators of the Indonesian killings of 1965 to 1966 as they reenacted their glory days for the film. I tried to rewatch both films back to back, but I could not because I find them incredibly disturbing. I am a completist and even the discovery of a readily available, longer director’s cut of The Act of Killing was not enough to get me to return to the film. I rewatched the majority of The Look of Silence, but eventually had to give up as the threats increased. Both films capture what it is like to live in a country that proudly glorifies genocide and cats the most violent as heroes. I love fictional violent movies, but hearing men and women laughing about brutal killings is chilling.

Oppenheimer’s documentary style is strange and immersive. It is not exactly poetic because he participates in some degree in what the film is memorializing—as a voice heard off screen, a topic of discussion or even possibly showing cut scenes from his movies. His film has no narrator to explain what we are watching, and the images and audio are not always instinctually paired though as the film unfolds, it makes powerful, emotional sense in retrospect. It requires patience, complete attention to detail and a willingness to encounter the unfamiliar and become comfortable with disorientation. A viewer just has to silently and gradually get acclimated by constantly asking, “What is going on? What am I seeing? Who is that person? What is the relationship between these people?”

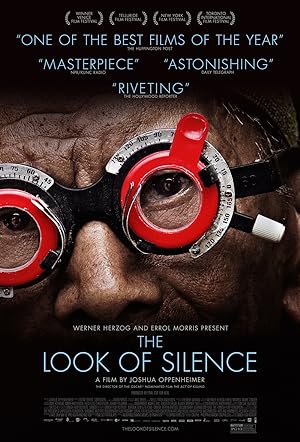

The Look of Silence’s protagonist is the younger brother of a victim of these killings who was born after his brother’s murder. Even though this film focuses on another culture, and I know nothing about Oppenheimer’s religious beliefs, there is something very Biblical about the way that this film uses the literal as a metaphor. Oppenheimer’s film evokes the Biblical theme of not equating having physical eyes with seeing the truth. Our protagonist is an ophthalmologist, and he uses the tools of his trade to engage the perpetrators and try to get them to repent at great personal risk to himself. When they get to talk about their glory days, it is talking about the past, but when he questions them using their standards against them, he is being “political.” Lest you think that these elderly men are helpless, they clearly relish what power they still have and openly threaten him, but because he provides a service, he does not experience instant reprisal. They are eager to lap up all the praise of heroes for being murderers, but when actually confronted, deny any direct responsibility while simultaneously suggesting that they could still kill anyone today. The protagonist and a lot of the crew decided to remain anonymous so they would not get persecuted after the film, but considering that they are not physically disguised, I do not understand how that is possible.

The Look of Silence spends a lot of time on focusing on the protagonist’s face as he watches video footage of the perpetrators joyously recalling the murder of his brother or others like him. Oppenheimer frames the footage by showing the clips on an old three-dimensional television set instead of cutting the clip seamlessly as if it is a part of this movie so unlike The Act of Killing, as viewers, we are conscious that we are watching something whereas no such framing exists when Oppenheimer films the protagonist. We are supposed to be empathizing with the protagonist.

The Look of Silence recreates moments for the protagonist to enter the literal space that the perpetrators occupied in the past when they committed crimes against humanity and recreated it for posterity. In one scene, a survivor accompanies the protagonist. Oppenheimer’s film is a perfect example of showing, not telling, by allowing his audience to compare and contrast the demeanor of the perpetrators with the survivors to the same memory. It is the difference of attending a reunion versus a funeral. The most editorial that Oppenheimer provides is the distancing of how he shows them-the perpetrators at arm’s length on a television screen and the survivors of the violence without a frame.

The protagonist is a viewer like us, and his response becomes our compass. We are walking in his shoes. We get to see his family life, which includes his parents and children. He is a quiet, gentle man with a sensitive face. In American culture, regardless of gender, other than the cultural expectation/pressure on Black people to dispense forgiveness, everyone else usually responds to the murder of a relative loudly, with outrage and wanting revenge. In a society where the murderers are in power, such a response is not permitted, not practical. Is his response instinctual and/or a necessity?

The Look of Silence also meditates on the generational role of women in this society on both sides of history. The protagonist’s mother gets the most screen time of any of the women. Her memories are the ones treated like gospel and an accurate recollection of the past. Oppenheimer waits a really long time to reveal the protagonist’s wife. Her role is a kind of cliff hanger to confirm our suspicions of their precarious place in society. Unlike her husband, her predominant demeanor is present day concern for him and her children. There is always the silent threat that history could repeat itself because the perpetrators are unrepentantly in power. If the protagonist is actively trying to change the hearts and minds of the perpetrators and children to save the future, his wife is the grounded reminder of who will be left holding the bag if he fails. She will inherit her mother in law’s legacy of justice denied and carrying the burden of memory.

In contrast, even if women were not hands on perpetrators like their male counterparts, they were often victims or complicit by being eager consumers/spinners of the perpetrators’ stories as wives or daughters. Depending on the generation of these women, their responses either bring hope or fury. The wives deny or shift blame once confronted with undeniable proof, video evidence of husbands’ admission of murder or the wife’s presence during the confession, of their knowledge of their husbands’ guilt. They never apologize and are devout wives until the end carrying water for their demon lovers even if deceased. The daughters are more ambivalent starting with pride then arriving at shame. It is harder for them to deny the truth once confronted with it.

The Look of Silence is a great documentary, but not an easy one to watch. Besides subtitles and an innovative narrative approach to telling a still unresolved story of horror, it is uncomfortable to watch because the danger is omnipresent, there is no justice and the sword of Damocles that all of this could happen again and hurt the protagonist and his family, the best people in this documentary, is a terrifying reality.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.