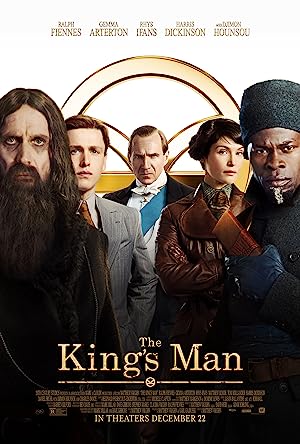

“The King’s Man” (2021) is a prequel to the Kingman franchise that reveals the roots of the secret agency. The benevolent, pacificist Duke of Oxford (Ralph Fiennes) tries to discourage his son, Conrad (Harris Dickinson) from going to war, prevent international conflict and protect the Crown. Will he succeed while maintaining his principles?

“The King’s Man” may be my favorite entry in a problematic franchise. I always preferred Colin Firth to Taron Egerton. The prequel tricks audiences into accepting the fifty-nine-year-old, single and child free Fiennes as the protagonist and an action star. Fiennes may be most popular for taking over as M after Judi Dench exited from Daniel Craig’s James Bond films, but for viewers familiar with his resume, Fiennes is a serious actor who directs artistically ambitious, uneven films and did not seem comfortable when he was at his most handsome. As he is literally letting his hair down, this work is him at his lightest and most affable. Popular culture rarely depicts loving and accepting fathers, and as Oxford, Fiennes uses his customary downturned scowl to brighten every time he shares the screen with Dickinson, especially when Conrad fears that he has angered his father. Matthew Vaughan, the English filmmaker who has adapted the original comic book series, “The Secret Service,” and allegedly has aristocratic roots to the Hanovers, gives a revisionist makeover to British aristocrats who are not known for their warmth.

“The King’s Man” puts us in the position of rooting for the British Empire. Oxford is apologetic and tries to reform historical British wrongdoing, especially regarding colonialism. Having an African man, Shola (Djimon Hounsou), and a nonsexualized, white woman, Polly (Gemma Arterton), as his (subordinate) colleagues gives him the appearance of being progressive, and as women and Africans, thus black people, as endorsing the British empire. If I was younger when I accepted and did not question the idea of tokenism (there can only be one), I would not notice that they have no lives outside of him whereas he is allowed to have a family. Movies normalize the idea that one is enough, and the majority consists of white men. They exist to serve him and the Empire. They love Conrad as their own. Ignore historical racism and classism which would prevent them from having their own personal relationships, friendships and romances outside of him, and caring for their own children because it would interfere with their service to him. The film normalizes women and people of color being fully satisfied with only having professional, not personal lives, and even teases the idea of Polly having a crush on Oxford as opposed to masters sexually harassing their servants.

I do not expect “The King’s Man” to be historically accurate. I love fantasy, but the film serves a purpose and mixes enough fiction with fact to supplant the truth from our collective imagination. There is a reason that colonized people become Anglophiles. Vaughan, like his associate Guy Ritchie, is embracing a regressive fantasy of aristocrats, but instead of gangsters, they call themselves “rogues,” which reframes an embrace of the establishment to be cool. Instead of being the foundation of the establishment, they are viewed as the scrappy underdogs against a unified set of bad guys whose goal is to destroy the British Empire by starting World War I. If the comic book series was not from a Marvel imprint, Icon Comics, Wonder Woman would not feel out of place if she suddenly appeared.

The Shepherd, whose identity is hidden until the denouement, leads the bad guys, who include the assassin of the Austrian archduke, (Joel Basman) who in real life was a member of a smaller conspiracy group, Rasputin (an unrecognizable and scene-stealing Rhys Ifans), Lenin (August Diehl), Mata Hari (Valerie Pachner), and Erik Jan Hanussen (Daniel Bruhl). The creation of the Kingsman is a direct defensive response to The Shepherd’s assault on Great Britain. The story retains the basic framework of historical events, but creates a fictional unity among the bad guys to instill a desire among viewers to have an equally strong unified response to stop the villain, i.e. a yearning for the real British Empire. Even as I was entertained, I was horrified and aware that most viewers would not have a basic understanding of World War I to be conscious of how the film is manipulating them. Pacifism is not the answer. War, the building blocks of empire, is.

“The King’s Man” is also another British film that seems to villainize Scottish people more than more recent historical enemies such as the Germans. The Shepherd is Scottish and the head of the villains. Like Christopher Nolan’s “Dunkirk” (2017), a Scottish regiment serves the same horrific role as they did in Nolan’s war epic as dangerous allies never to be trusted. Some British filmmakers seem to have an unofficial agenda to demonize the Scottish people and minimize the historical role of Germany as the enemy by rendering them invisible in Nolan’s epic or making them fools with the Scottish as puppet masters.

If the goal is to preserve the British Empire, it makes sense that the film would see a historical, former enemy to that empire more of a threat than a foreign country. As an American, it is still disconcerting to witness because Scottish people were literal kings of Great Britain in 1604 despite a history of independence and refusal to bow to England. Without Great Britain, there is no British Empire so technically should not Scotland be thanked for starting this juggernaut? Comparatively the Windsors have weaker native roots to the establishment as imports with German origins than the Scottish to the British monarchy. Though this film lives in a world without division between Protestants and Catholics (Rasputin’s closest religion of choice would be Eastern Orthodox though he is considered a charlatan), it is the true underlying division. This film continues a civil war without explicitly acknowledging it. British popular culture is weird.

There is a post-credits scene that teases the possibility of a sequel to “The King’s Man,” but when you find out who the next villain is, the reaction may be horror. While the prequel’s plot twists history, it is a part of history that is not well known. Vaughn teases that he is planning to go into the deep end of the pool, a pool that Quentin Tarantino managed to create an alternate version of history and emerge relatively unscathed though some critics did not appreciate his revenge fantasy, but at least Tarantino was rooting for an actual underdog. Vaughn roots for the establishment. When he revises history, Vaughn wants the powerful to have more power if he likes them, villainizes allies, erases villains’ true motivations and heroes’ culpability. What does that look like in a World War II flick? When Tarantino seems like a wise statesman in comparison to Vaughn when it comes to European wars, I worry. I can enjoy this film because I do not believe that Scottish people are in literal danger if people watch and enjoy this movie. A movie about World War II is another story. I do not want Germany’s role to be minimized or played like a supporting character. While the British Empire suffered, they were not the ones that we should be primarily worried about in that story. Since 2016, fascism has grown in power internationally, and anti-Semitism is an unfortunate reality that increases. The Boer war did not just have Boers as victims. Africans were in those concentration camps. I am not confident that Vaughn can make a fun flick that will not damage the lessons of World War II that the world has still failed to learn.