I watched The King of Comedy because I wondered if it heavily influenced Joker, which duh, yes, but hey, I was not even sure if I saw that film so I did not want to throw around references without being certain. Even though I am really into film, I am not into Martin Scorsese. I am not challenging the idea that Martin Scorsese is a genius, but unlike many auteurs, I have never systematically felt compelled to watch all his films. I have watched many of them, and because I acknowledge that I saw and enjoyed the copycats before his films, I recognize that I watch his films at a disadvantage. He innovates. Others copy him. I watch the others and think that they are breaking ground then watch his films getting a vague whiff of déjà vu when it should be the reverse. It is not fair, but it consistently happens. Or I have seen so many clips from his classic films that I only think that I saw them, but I have not. Starting with The Age of Innocence and Gangs of New York, I started seeing his films first before they were copied, and he just is not one of my favorites though I appreciate moments and huge swaths of his films, but rarely the entire film. I am a philistine, but Joker is a perfect example of this problem. I see Joker then praise it for ground that Scorsese already laid the bricks. It is not fair, and I have no idea why he encourages this phenomenon—he was going to produce Joker, but got too busy with The Irishman, which I still have not seen, to do so.

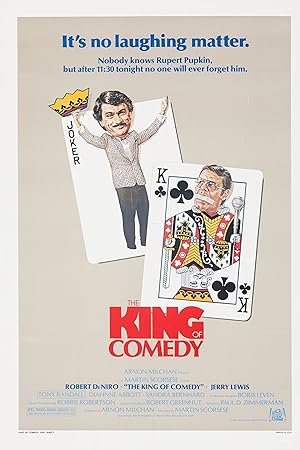

The following review is less going to be a review devoted to Scorsese’s classic as an opportunity to compare and contrast Scorsese’s vision with Phillips’ film, which instinctually feels like comparing Einstein with some kid in a classroom who accidentally got the extra credit answer correct on her physics exam and now is being taken seriously as if she is a genius (spoiler alert: she is not, and that person was me). If you haven’t seen Joker, there will not necessarily be spoilers, but it will be referenced so you may get bored out of your mind. The King of Comedy focuses on two characters, a famous talk show host like Johnny Carson, named Jerry Langford, who is played by Jerry Lewis, and a fan with ambitions to be like him, the titular character whose real name is Rupert Pupkin, whose accidental encounter with Jerry further fuels his ambition/delusions of success. Robert DeNiro plays Pupkin, but it is one of his least DeNiro like roles. Imagine the stereotype of the guy in his parents’ basement but just a smidge more personality and talent so he can pass the initial sanity test, but not for long.

My mom decided to watch The King of Comedy with me, and she could not tell when Pupkin was delusional or not. I could, but not with one hundred percent accuracy. I initially thought the weekend getaway sequence was a fantasy until the servants reacted. This movie is not mom’s typical fare so I think that Joker would be an anathema to her because it is so bleak and not rooted in objective reality. Pupkin may be a madman, but even his delusions seem more real than Joker’s. I think that it is the difference in the directors’ relationship with fame and Manhattan. Even though both directors are from New York, I have always appreciated that Scorsese’s New York feels real. He is more like a documentarian, and he is faithful to the city. The famous and the ordinary share the same streets. Phillips’ view of New York reveals perhaps a childhood fear of his surroundings. He is slightly older than me, but our formative years occurred when the city was at its lowest point. His depiction of New York is bleak, joyless, dark without an ounce of normalcy. The famous only exist in his spheres, and when they step outside of their realms, the city consumes them. He is like an outsider’s fever dream of New York whereas Scorsese feels as if he is home even when he explores the margins. My New York really is a mix of all segments of society, which is one of the reasons that I love it.

The King of Comedy gets that on a lesser level, Jerry is also a product of this city, a little crazy though more rooted in reality, but just as potentially dangerous given the right set of circumstances. Scorsese has a Rashomon perspective in each scene without having to make us slog through the same scene from different characters’ points of view. Phillips has a naïve view of the haves as being unable to exist in the world of the have nots or when confronted with the have nots whereas Scorsese gets that Jerry came from the have nots and is still like them, but he just used his reptilian brain to a better advantage. He did the work. Lewis does a fantastic job either being himself or depicting a character who at his core had to work hard to be personable, engaging and approachable, but really resents it. He is a man who had to learn how to be accommodating like a woman, but truly feels as if he should not have to (and he is right). He has so much pent up rage and does a terrific job of silent, seething anger, completely put upon and astonished at being at the mercy of idiots instead of being terrified. I also loved the brief moment when Scorsese reveals that he is not the top man in his show, but the producer is. There is always a bigger fish.

The King of Comedy has better women characters than Joker and treats race in a more incidental way, which is not an instinctual comment that I thought would apply to Scorsese, but it is true. If there is a reason to love Scorsese, he understands that women are people with the same flaws and equally as dangerous as men. Sandra Bernhardt’s character is a crucial factor missing from Joker—another crazy person who gets to be a foil for the delusional protagonist. They understand that the other is crazy yet think that they themselves are actually sane. There are not as many black characters in Scorsese’s New York as there are in Phillips, but the one that exists is a normal person whereas most of Phillips’ black people are women who could be viewed as antagonists to Joker. Scorsese’s lone black woman may be the most ordinary person in a movie filled with nuts. We see her visible deflation in each scene when she realizes that she is wasting her time, but to a lesser degree, she is also attracted to fame. I related to Cathy Long, the gatekeeper who probably has more power and expertise than Jerry because of her proximity to the producer, but has to waste her time dealing with the protagonist and conform to professional standards of conduct and gender norms in her exchanges because of her gender and her lack of being seen as an important person. I do not relate to anyone in Joker. There are no real people. I love that Scorsese’s film has such a variety of women, but Lewis contributed my favorite one during the payphone interaction between Jerry and an elderly woman. This film is not just about fame though the phenomenon occurs mostly with famous people. When people want something, anything, and you say no, you learn a lot about the true character of a person based on his or her reaction. Sanity is hearing and accepting the other person ‘s position even if one does not agree with or like it.

Oddly enough Joker’s protagonist works harder than Pupkin in The King of Comedy though they share the same delusion regarding what they deserve. Pupkin genuinely seems more innately talented. Phillips wins in not entirely shrinking back from violence whereas Scorsese cannot seem to bear to take the film to its natural conclusion because he loves his leads, which for a filmmaker who has given us some of the most violent, affable characters in cinematic history, is shocking, but I think that he did not want Jerry to get hurt and on some level, he did really believe that Pupkin is harmless though the violence is there as shown in the delusional fantasy in the office when Jerry manhandles Pupkin while complimenting him. Jerry is doing to Pupkin what Pupkin actually wants to do to Jerry-obliterate his talent and exchange places with him. It is true that in the real world even dangerous people resist giving in to their most dangerous impulses, but I felt as if the gradual escalation deflates in an unrealistic manner. Scorsese believes that Pupkin can be satisfied with fame or maybe the interception is enough, but the minute the head of the security guard kept calling Pupkin (deliberately?) by the wrong name, I thought that someone should have at least gotten hurt and not necessarily Jerry.

Or maybe Pupkin is genuinely saner than Joker. There is one unanswered question in The King of Comedy: what is the catalyst for Pupkin suddenly deciding that he needs to resolve all of his issues from high school seventeen years later? When we meet him, before he seizes the opportunity to connect with Jerry, he decides that autographs are not good enough, it is time to profess his love to Rita and become famous. What happens before that point in the movie to suddenly create this sense of urgency in his mind? I have no idea, and I would love to know whereas Joker seems to always be on the edge of psychosis and snapping. Somehow Pupkin has been harmless and existing adjacent to the famous unnoticeable for decades. I have a theory. I think that in Scorsese’s film there are two levels of delusion: the fantasy of fame and his life at home preparing to be famous. During that time, it was expensive to develop large photographs then make cardboard cutouts of people. Recording equipment is attainable, but not for someone without a job. There is also ambiguity regarding his mother—think Bates Motel. Pupkin’s most honest moment is during his comedy routine at the denouement, which shows that he gets his situation. He is really homeless, and whenever we see him at home, it is not really his home, but his imagination of his home life. He is desperate. The hint is the moment when he is in front of a large wall covered with a photograph of an adoring audience, and he is just basking in their adulation, which feels like a sad reprise of Jerry accepting the applause from his audience and gesturing that he wants a little more. That wall is larger than an average home would have, but it is reasonable for Pupkin’s mind at that point.

The King of Comedy’s ending is actually fairly funny and absurd how as Pupkin’s escalates his demands, now male professionals are forced to interact with him and take his demands seriously. It becomes a comedy of manners-be polite to the madman while instinctually trying to default to your usual script. The most hilarious reaction is when Jerry’s lawyer’s response to the situation is to threaten to sue people. How is that tool going to be effective in this situation? If Pupkin is crazy for not understanding how to achieve his goals or being resistant to recognizing the reality of his predicament so is the lawyer and the law enforcement officer. These scenes kind of reminded me of a Roman Polanski film and recognizing the limitations of societal rules in the face of insanity.

The King of Comedy is the original and more organically real, but Joker is visually more interesting and is more appealing because of its cathartic violence yet neither film is the kind of movie that you watch and enjoy. Both films pull punches at odd times which feels unfaithful to the characters and indicates more about its creators’ hangups, but one film feels rooted in love and an attempt at understanding and the other feels as if it shares the resentments and the delusions of its protagonist then secretly takes delight in his need for vengeance instead of trying to truly understand how that need originated.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.