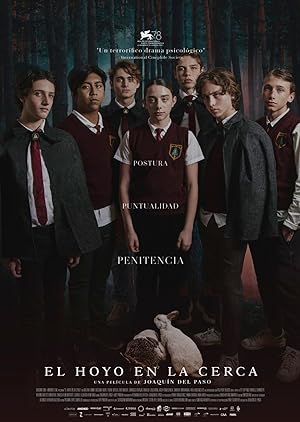

Annually, for generations, a class from an all-boys Catholic school visits a countryside camp, Centro Escolar Los Pinos, as a rite of passage. “The Hole in the Fence” (2021), a Mexican-Polish film, depicts one such trip. Director and cowriter Joaquin del Paso and cowriter Lucy Pawlak’s sophomore collaboration takes viewers on an unsettling birds’ eye view of a perpetual cycle of manipulation. The camp creates tomorrow’s leaders and ensures that regressive agendas continue.

The premise of watching adolescent boys is already terrifying, and many compare this film to William Goldings’s “Lord of the Flies,” a novel about marooned British students. “The Hole in the Fence” is not a horror film yet it is like “Midsommar” (2019) meets “Jesus Camp” (2006) in the way that it depicts a closed community and their society’s practices at special events. The slow burn film feels like an allegory for the perpetuation of colonialism and plunges viewers into a world where the men responsible for their education, with the blessing of the boys’ families, thought that these already cruel children—racist, classist, homophobic, sexist—were too selfless, too thoughtful, and too questioning of authority. These teachers are also victims of this system, but they see it as a privilege and are fervent true believers. These teachers practice and encourage the opposite of what they preach.

While watching “The Hole in the Fence,” notice the steps to brainwashing.

Isolation: taking the children to the middle of nowhere; taking away their cell phone access; separating them from the locals; not allowing them to talk to their family or law enforcement. The fence and gates enforce this isolation though it is under the guise of separation. By deliberating making loud noises when they enter the town and making the terrain rough along the path to the town, it encourages the children to isolate themselves further and associate the town with hardship and danger. While at the camp, they burrow into a chapel that is built like a bunker underground to further bond the boys to each other and make the world feel like a terrifying place.

Submission: instilling fear of others; offering solution for that fear; simultaneously dismissing that fear; drugging; sleep and food deprivation; encouraging bullying, especially on those who are different. No one needs to be at the camp to feel that fear. Media such as the television series “Narcos” already cultivates fear of their fellow Mexicans who are poor and makes the boys believe that the villagers are traffickers, kidnappers, and robbers.

Rigid system of reward and punishment: using the veneer of Christianity to equate the elite with saved and the indigenous as the damned, infected, dead, beasts, uncivilized, savages; physically beating anyone who challenges authority; creating a sense of superiority through charity work; false accusations that encourage false confessions to elicit compliance from the rebellious; punishing by pretending to withhold an activity that the teachers want the children to participate in, so it feels like a reward to the children. By the end, even the most critical thinking or different child drinks the Kool-Aid and transforms into their ideal person. They do bad deeds and justify it by projecting the worst aspect of themselves on the other. The teachers even assert dominance over a wealthy, powerful government official.

“The Hole in the Fence” carries the mantle of “Get Out” (2017) by including people of color in this oppressive dynamic and watching how they get absorbed into the majority as an exception and become complicit perpetrators. Initially it was heartening to see diversity in the film. The adult version is Tanaka (Takahiro Murokawa), the boys’ favorite teacher, who seems approachable and humorous compared to the other teachers. His schtick is revealed to be a sinister act in the way that he pushes the agenda in a veiled, insidious way as if he is on the boys’ side. He is a double agent. He pretends to be injured then encourages the children not to help him to encourage them to ignore any shred of humanitarian impulse they still hold. To get a sense of how he became the man that he is, there is a scholarship student, Eduardo (Yubah Ortega Iker Fernandez), who has brown skin like the locals. Initially he is the butt of relentless ridicule, but his time at the camp encourages him to stop fighting back against his bullies and abuse people who are like him in appearance or sentiment like Joaquin (Lucciano Kurti). Also the servants have to participate in their oppression without protest.

“The Hole in the Fence” is so literal and straightforward in its approach that it feels silly to call it an allegory when there is nothing hidden. There is still subtext. The filmmakers show the teachers conspiring, and the dialogue lays out their plan; yet visually the film remains mysterious. The movie opens on an initially idyllic, untouched, natural place when the image is cropped. The soundtrack is filled with dulcet tones that evoke paradise and storybook time. Eventually a long shot reveals that it is a highly cultivated place carved from nature with landscaping thanks to local, brown-skinned gardeners wielding machetes. It is a visual metaphor about colonization. There is only a glimpse of paradise and nature pre-colonization. By the denouement, the complete absence of nature and a largely inhospitable environment dominates.

One tool of colonization is to preach religion, but not adhere to its tenets. The teachers are anti-Christ figures, who allegedly worship, but subvert Jesus’ teachings by discouraging coming to others’ aid. Even the school’s symbol, a cross and a pyramid, seems more mystical and syncretic. Matthew 7:15-20 states, “Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravenous wolves. You will know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes from thornbushes or figs from thistles? Even so, every good tree bears good fruit, but a bad tree bears bad fruit. A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a bad tree bear good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. Therefore by their fruits you will know them.” Remember the birds and the fruit in the opening shot.

In an unusual turn of events, even though the camp is vigilant against anyone entering the camp, a brown skin man briefly observes the campers as they birdwatch.

No one notices or interacts with him except two kids. Jordi (Valeria Limm, who is a transgirl actor), a perspicacious cis boy, who openly scoffs at the school’s teachings, but still reacts in fear at this man. Later another student, Edwin (Raul Vasconcelos), who is the most physically broken of students, crosses this mysterious man’s path. Their interaction reveals this man;s identity as he is the only one to help Edwin take steps to heal as opposed to the camp’s young EMT vest wearing poseur. This man is the Jesus figure, not the teachers, especially if contrasted with Professor Monteros (Enrique Lascurain). Compare the way that this man versus the teachers treat Edwin. By the end of “The Hole in the Fence,” a viewer is left wondering if the camp’s last activity always ends in this manner. The neighboring town’s poverty seems less a flaw than a feature. The colonizers’ descendants are just as much of a threat to the indigenous as their ancestors.

Side note: six shipwrecked Tongan Catholic boys cooperated and survived on an island for a year.