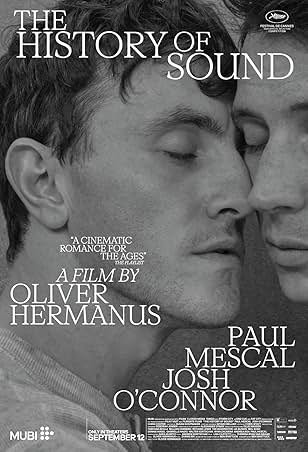

“The History of Sound” (2025) adapts two short stories from Ben Shattuck’s second book, “The History of Sound: Stories” (2024): a story with the same title as the movie and “Origin Stories.” The naturally gifted Lionel Worthing (Paul Mescal) leaves humble life in Kentucky to study at the Boston Conservatory of Music where he meets David White (Josh O’Connor), who shares his taste in folk songs. The draft for World War I interrupts their romance, but their time together affects the course of Lionel’s entire life.

To enjoy “The History of Sound,” a moviegoer must favor folk music and love-of-a-lifetime stories that only exist for a short, brilliant burst. Consider yourself warned. If you are expecting the love story to span the entire movie, which starts in 1910 and ends in 1980, and have ample opportunity to drink in the spectacle of Mescal and O’Connor swooning over each other, think again. You better have a camel’s constitution and enjoy what you can. It is Lionel’s story. Life in Kentucky is depicted with a Terrence Mallick -esque lyrical eye. In the US, the colors are duller even before David returns from war and explains that war “made everything dimmer.” Older Lionel (Chris Cooper), who narrates off screen until he appears in the final act, describes a world more vibrant than the one shown onscreen. Lionel finds this world to be where he is happiest: a wooden, drafty shack, a country terrain to work on and walk through. Even the scenes in Boston have this tone. It adds to the historical sheen of the film to seem as if it was as close to black and white while still being shot in color. It makes a rough kind of sense that if Lionel sees with his ears, it is the sound that is richer than what meets the eye.

“The History of Sound” is one of the rare movies where the relationship between a father and son is foundational, not the villain origin story of a protagonist. Lionel Sr. (Raphael Sbarge) is depicted as a man who was able to convey the magic of the world to his son through music and fire. When Lionel hears David sing a song that his father sung to him as a child, he is immediately attracted to him. The attraction is based on a common interest, music, which Lionel associates with home, and physical attraction. No need to become an armchair psychologist and invoke an inverted Oedipus complex, but it is there.

David is a step behind during the first encounter until Lionel knows a song that David does not then David is all ears. David pretends to act cooler about life and loss than he feela and is deliberately furtive about his past. With the advent of World War I and the suspension of school, Lionel is hurled back home with emotional, socioeconomic echoes of “Charly” (1968). With a taste for the broader world, “The History of Sound” intertwines a love story with an existential crisis: what kind of life do you want? There is not talk of the Spanish Flu, but the shadow of death hangs over the US. Do you have a duty to your roots even as it is dying, your love, your happiness, a broader cause or yourself? For Lionel, the answer changes, but he lands at the last option after trying the others and finding various options closed to him or unsatisfying.

It is not an accident that the trailers for “The History of Sound” is filled with scenes of Lionel and Paul collecting songs in Maine from ordinary people during their happiest season. It is the best part of the film, and the love between Lionel and Paul is palpable thanks to the banter, physicality and deft projection of emotions on the faces of O’Connor and Mescal. The moviegoers, like Lionel, will feel the loss when Paul is no longer a part of Lionel’s life. The film is not heavy handed, and there are no scenes of the pair shunned for being in a same sex relationship, but while Lionel makes it clear that he has no problem following Paul anywhere, Paul closes that door firmly. While there is a flash of Paul’s resentment at Lionel’s assumptions about his life experience based on their class and regional differences, it is not the reason for the separation.

The rest of “The History of Sound” is filled with Lionel trying Paul’s passing suggestions of what he should do with his life, which means lots of lovers, trips to Europe, gaining fame and fortune with his voice as the golden ticket or looking for the voice of God using Paul’s vague, anecdotal directions. South African director Oliver Hermanus depicts Europe with more vibrant colors as if it is the New World and the land of opportunity. It is also where Lionel is most miserable, so he follows his heart back home to Kentucky, song collecting and Paul. It is in this part of the movie that the significance of earlier passages should start to hit movie goers’ solar plexus, and if it does not, then the details were missed. For instance, Lionel keeps lying on the hard ground or floor to harken back to his time camping with Paul.

“The History of Sound” feels like literature, and if reading is not your cup of tea, you should probably run. Shattuck adapts his work for the screen, and the deliberate pacing reflects that he must have successfully conveyed his vision to Hermanus. To other people expecting a more structured, dynamic story reminiscent of “All of Us Strangers” (2023), prepare to be disappointed. It is all Lionel’s story, and some may wonder if the Massachusetts middle class author married to Jenny Slate knows anything about being a Southern rural, gay boy or if Shattuck is engaging in a bit too much Jean-Jacques Rousseau romanticism of the common man then relegating the violence of American and global life to the furthest corners glimpsed occasionally. Lionel’s inability to go to war colors a reality that the dialogue claims that he has experience in yet does not show. It is a choice to make it a quiet movie and focus on Lionel’s interiority than the world around him.

“To love another person is to see the face of God.” The next line would be to hear another person is to hear the voice of God. If you remixed “Brokeback Mountain” (2005) with “Call Me by Your Name” (2017), with two age-appropriate lovers who know who they want, then you would get a sense of what to expect in “The History of Sound,” but it is also its own thing about living the best life for you especially when you cannot have what you want. While Mescal is a good actor, he is a bit too ephemeral to hang on to so when O’Connor leaves, it is harder to stay invested in the story as your brain screams, “When does O’Connor come back!” If a young Cooper or a young Kentucky born Michael Shannon played Lionel, imagine one of them with O’Connor. They could hold their own while being swept away.