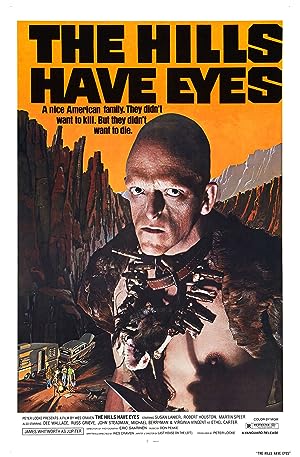

Less than five years ago, I saw the remake of The Hills Have Eyes primarily because that chick from Lost was in it, and it was before we realized that Lost was a complete waste of time and a disappointment only surpassed by the final season of Game of Thrones. Wes Craven directed the original so I knew that I would see it eventually, but the remake was so anticlimactic that I was not exactly eager to see it. Usually originals are better, and Craven deserves the respect that he receives as a horror director though we probably take him for granted: A Nightmare on Elm Street, The Serpent and the Rainbow, The People Under the Stairs, Vampire in Brooklyn, Red Eye, Cursed, the Scream franchise and Music of the Heart…ok, maybe the last one is just a good movie and has nothing to do with horror.

While Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes may be dated in many ways, it is still a timeless classic that works on multiple levels. Use Google or Wikipedia to discover Craven’s intended significance of the movie, but if you want a viewer to womensplain or viewersplain the deeper meaning that he may not have consciously intended, but clearly exists in the film, please continue to read.

The Hills Have Eyes is a glorious thematic story of the problem of the nuclear family, power and patriarchy. There are three families depicted in the film: three generations of human vacationers, the canine vacationers and three generations of a family that lives on or near the nuclear testing site, the home team. The nuclear testing site automatically makes viewers associate the latter family with abnormalities caused by exposure, a distortion of nature, and we are supposed to associate our image of the perfect American family in the same manner and start considering how they are just as innately damaged by the effects of a larger framework of power superimposed on nature in the form of a hegemonic American nuclear power structure. I don’t think that Craven just happened to make the head of the nuclear family into a retired detective, and Craven makes sure that we recognize that while his authority is never questioned within the family (and probably never while he was on duty), Craven shows that it should have been.

The nuclear family’s patriarch blames others for his faults. He arrogantly goes on other people’s property and unprovoked shoots his gun on their property with no repercussions. He also believes in primogeniture by leaving his only son in charge when he is neither the oldest person available to take charge nor the next oldest man after the patriarch who could be responsible. He makes a child responsible for a family. Perhaps his most damning trait is his failure to protect himself or his family in spite of supposedly having the most experience as a former detective. The Hills Have Eyes really hammers home the idea that authority and power are creations, not reality, constructs, not organic.

The Hills Have Eyes show how not challenging this power structure leads to more danger for the nuclear family and how it looks like in its most extreme form, the home team. Papa Jup expects unquestioning loyalty and obedience from his adult children, similar to a cult leader and the patriarch of the nuclear family. Also when artificial extreme power structures clash, it only leads to destruction and mayhem for everyone. Imagine a movie in which neither patriarch is so full of himself and high on his own supply. It leads to a different family dynamic and a different way of responding to the outside world. If I had to critique something in the film, it is that the only normal looking member of that family is also not a danger, but an outcast in her family and repeatedly punished for resisting the destructive behavior of her family. Her story parallels the story of the women in the nuclear family, especially the younger daughter.

The grandmother of the nuclear family is like most of the fifty-two percenters—more concerned with the language that her adult, married daughter uses to describe obscenities than the actual obscenity. The son, a child, utterly fails to warn his family of the threat and honestly spends most of the movie inadvertently putting his family in more danger than protecting them, but congratulations to the actor for probably running a marathon during the making of this film. It is only the women of the family who figure out how credible the threat is and respond instinctually and eventually effectively to repel that threat. Because they were complicit in their silence by respecting their father’s undeserved authority and failed expertise instead of questioning his authority when it could have made a difference, they have to deal with the consequences of his actions. Like many films during the Golden Age of Hollywood, the women characters realize that relying on men for their safety and well being is always a loser’s game. The elder daughter’s husband undergoes an intensive training with the thanks of the dog, Beast, played impressively by Stryker, who is the real hero of this film, in order to learn how to step up to the plate and fight out of necessity, not innate ability.

The animals, specifically Beast, is the quickest to recognize and respond appropriately to a threat. The most humorous moment in The Hills Have Eyes is when a character says, “Yeah well, if animals around here are smart enough to run radios, we’re up shitcreek without a paddle.” Well, animals are smart enough to do just that, but her assessment of the health of their predicament is erroneous.

I have no idea if the creators of the remake of The Hills Have Eyes understood the ideas that Craven’s original elicited from its narrative, or if they understood, tried and failed to revisit them or did not know and/or try. Maybe it is there, and I missed it because I was a different person when I watched it years ago, but I was more struck by the idea that the remake was about an urban man becoming a real man in the face of mortal danger, not like Craven’s classic, a critique of power and patriarchy.

Judge for yourself, but if you love horror, I would urge you to only watch Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes and skip the remake. If you are a completist like me, then you won’t be able to follow my advice so have a marathon viewing and discover what you value in your movies—better production values or a better story.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.