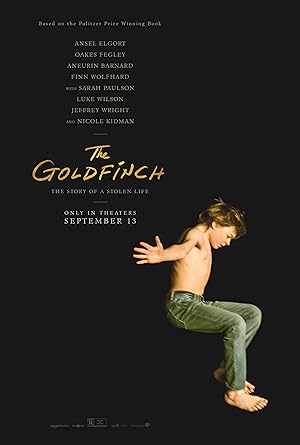

The Goldfinch is about Theo’s life at two different points after his mother dies during a terrorist attack: as a child and an adult. It is about how much the quality of a child’s life depends on those who make decisions for him and how little autonomy a child has in the trajectory of his life.

The Goldfinch has received poor reviews. After its premiere week, the number of showings has been dramatically reduced, and it will probably be pulled from theaters, which is usually objective evidence that the movie was not favorably received by ordinary viewers. On the other hand, one of those poor reviews from a well-respected site, which I shall not explicitly mention, incorrectly stated that the Met was known as the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, and I have sent an email to this site in the hopes that this error get corrected. Presumably this person is being paid, well rewarded for their insights and has an editor. All these voices objectively matter more than mine, a voice in the multitude crying out in the wilderness, but I think that they’re not entirely right. Like this mistake, it is just wrong enough to betray a lack of appreciation for what the movie does offer and get right.

The first rule of watching a movie is that a movie must stand on its own. It is unfair and unwise to compare a movie to a book. A movie or TV series that adapts a book is rarely if ever as good as the book. I try not to read the book until after I’ve seen the movie. If the movie did an adequate job, then I’ll read the book. If you’ve read the book, skip the movie. I think that a lot of people are going to see The Goldfinch because they read and loved the book. Don’t do that unless you thought that the book was too complex.

I wanted to see The Goldfinch for several reasons. I love the Met. My mom took me there frequently. I worked there one summer in the medieval section. Whenever I visit New York, I try to drop in and see my favorite sections. If I was warned that while a pivotal event occurs at the Met, the Met is not my Met, but mostly a site of destruction like the World Trade Center on 9/11, I probably would not have seen it, but the same emotions that I associate with that particular museum is similar enough to the character’s undercurrent of sadness mixed with nostalgia that embody his attachment to the titular painting that I didn’t feel disappointed. I also saw it because the cast is generally phenomenal. I knew that the film was practically two and half hours, which is a challenging length for any movie, but I understand that they were trying to adapt a novel about a person over two different periods, at thirteen and twenty-one years old. If it was truly faithful to the book, it probably would have been longer, two movies or a television miniseries.

The Goldfinch is a movie whose parts are stronger than its whole. The performances of all the actors during the childhood sections of this movie are phenomenal, but the adult portion is uneven and is almost unintelligible and ridiculous in terms of plot. The adult section is almost Ben Is Back bad and is only redeemable because some of the remarkable actors who appear in the childhood section also have a recurring role in the adult section. Don’t worry. The dog is never hurt. The adult section feels dissonant, cheap and sensationalistic in comparison to its subdued, textured and subtle childhood section. It feels fictional, out of time, oddly governed by old fashioned rules whereas the childhood portion feels emotionally universal and specific in details: iPods, foreclosed, desolate neighborhoods, etc.

Oakes Fegley, who plays young Theo, is already a thespian. If you want to know if an actor is good, look at his hands, and there are scores of great hand performances in The Goldfinch. I don’t mean when someone slams their hands on the table. I mean when something more important is going on, and the corner of your eye glimpses someone’s hand betraying what is really happening. A good actor uses hands like a lie detector. They always tell the truth. Fegley has already figured this out. Lately I haven’t enjoyed films with little boys as the protagonists, but Fegley shows that those movies did not have strong enough actors in the lead. Nicole Kidman’s performance was perfect, of course. She delivers an uncharacteristically deliberately restrained performance, but even in her coldness, she is able to emanate her character’s inner feelings because if you need an actor to convincingly shine love on a complete stranger, get Kidman. I hate that she is so good because her politics are so cringeworthy, but quality is quality. I was so excited that Jeffrey Wright got so much screen time because he usually doesn’t, but he is the steady, warm, moral core of the film. I have no idea if my reading of his character was accurate, but I have a soft spot for gay uncles so that only made me love his character more. Finn Wolfhard, whom I recognized from It, also managed to play a complex role: a character whom you know is not good for Theo yet is nevertheless his soul brother. Sarah Paulson is always on point, but in this movie, she acts startingly against type. It was a little shocking that the only attempt at restraining bad behavior is attempted by her character. She manages to be sympathetic and inadequate.

The Goldfinch’s early themes of belonging are strong. If you have to be invited, then you don’t belong, and as a kid, belonging and security are essential. The problem with the adult version is we know that Theo likes to read however he seems to be oblivious to pulling a Great Gatsby. The narration indicates that he hates his life, but it is like he is a character out of an Edith Wharton novel whereas when early Theo experiences the tonal shift of his foster family with his biological family, it is obvious which world he actually belongs. Because his mother is a mystery, but Theo loved her, it makes you wonder how his parents ever got together, how his mother was able to afford for him to hob knob with his Park Avenue classmates and have an educational trust. (As a New Yorker, it bugged me that I didn’t know which school he attended.)

The Goldfinch also has resonant scenes of synthetic comfort. Physical comfort is noticeably lacking so it is substituted with offers of alcohol or prescription medicine by every character. The only physical connection is abuse usually at the hands of fathers. There is also the idea that only chosen brothers, equals, are able to bridge the exile of tragedy and meet on a common ground of truth without ceremony and formality. For the most part, I think that the film nailed what it is like to be a child in New York and what it is like to be a New York child thrown among real children. They may be the same age, but the actual level of maturity wasn’t.

I don’t think that either romantic storyline worked. Outside of Wright’s performance, I don’t think that The Goldfinch successfully conveyed why the fate of the titular painting was important in an objective sense. I remember when The Scream was stolen, and I felt this wave of outrage because now who knew how many potential artists would not exist because they could not see it and become inspired by it. Some characters that are briefly introduced were probably important in the book, but should have been left out of the movie—sorry, Mr. Silver and Tom Cable. I’m not going to blame Ansel Elgort, who plays the adult Theo, for the hot mess that his section was. He didn’t transcend it like Aneurin Barnard did, but he wasn’t responsible for it and did his job. It just felt absurd. I hate the how we got here narrative structure.

The Goldfinch is a visually beautiful movie, but if you decide to see it, the childhood section is startingly better than the adult section. I almost wish that I could give you permission to fast forward through it since we don’t get a real resolution on what happens to Theo, but if you’re interested in the fate of the painting, you’ll have to watch the whole thing. It is a magnificent mess.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.