This review was originally published on Roarfeminist.org

When I read that a movie is based on a true story about a dysfunctional family, I add that film to my Netflix queue. Why would I want to see something that depressing on the big screen for fun? The weekend is only so long, and real life is already pretty depressing. Also before I started watching Brie Larson’s work (or heard about her snub of Casey Affleck at the Oscars), Hollywood marketed her as the next young actress that they decided to make big like Jennifer Lawrence, whom I actually like, but she gets miscast in roles that should probably go to older women, or Anne Hathaway, who seems like a hard worker, and I am sure is a lovely human being, but when I think of memorable performances that only she could do, crickets. It is not just actresses who get this treatment. When Queen of the Damned was being advertised, the announcer’s gravelly voice said “Stuart Townsend” as if I should know his great work. Who? One more name: Shia LaBeouf. Let the work speak for itself if the person is an unknown quantity otherwise it creates the opposite intended effect—it repels me.

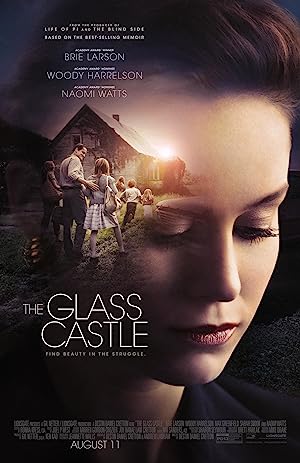

I first saw Brie Larson in Short Term 12, a magnificent, understated independent film directed by Destin Daniel Cretton. When I realized that Cretton and Larson were teaming up again for The Glass Castle, I broke my own rule and decided to see it opening weekend in theaters. I did not realize it was an adaptation of a book, but after seeing the film, I am eager to read it. It is about a young woman, Jeannette, on the threshold of a renowned career in writing as a gossip columnist, but she does not seem frivolous or vapid, and is in a happy relationship with her financially successful fiancé played by the magnetically charming and eternally affable Max Greenfield (best known for his work in New Girl).

If I had to describe the adult Jeannette, I would equate her to classic Hollywood’s dame, a real pistol, a Barbara Stanwyck-type whose trenchant wit and severe look were either her weapons or rewards. This was a woman who knew how the game was rigged, and then played it with sardonic commentary that would make the riggers squeal in delight. Larson wisely plays her not as a woman who is desperate and therefore sells her soul for comfort. She is making a life, and if it does not quite fit, she will defiantly confront anyone who challenges her to say, “Could you do better?” Larson uses her unblinking gaze and confidence to dispel any notion that she is a mercenary. She does not compromise.

The Glass Castle is a period piece, and in my opinion, the most convincing period piece of the summer of 2017 which seems to be full of them (Atomic Blonde, Landline, Wonder Woman). The film toggles between the adult Jeannette, who lives in 1980s New York City, and Jeannette as a child starting at the point when she experiences her first trauma as a result of negligent parenting. Cretton shines at using movies to morally condemn abuse in all its forms without being prurient or explicit. He is unflinching emotionally and psychologically, but tasteful and respectful. Cretton is able to depict how a child would initially be delighted by her parents’ sense of adventure and eagerly conspire with them, and then gradually decreases the ratio of wonder to horrified and disappointed recognition of betrayal as the child gets older. Cretton is adept at developing the tension between love, loyalty, anger and survival.

Even though The Glass Castle is Jeannette’s story, what makes it so textured and nuanced is the sense that all the other people in her life, particularly her siblings, have as interesting a story to tell even if we never see the story from their perspective. You don’t need a collection of famous actors to create an ensemble cast. You just need fully realized characters paired with skilled and talented actors to make a story feel like an organic whole rather than poverty or suffering porn filled with tropes and clichés.

It is kind of hard to believe that Woody Harrelson was not the first choice to be cast as the father in The Glass Castle. Harrelson seems to have a monopoly on alcoholic, emotionally tortured father figures that you can simultaneously empathize with and are infuriated at their behavior: The Hunger Games franchise, True Detective, and The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio. Harrelson brings an emotional nuance to his masculinity in crisis roles, particularly for a specific financial demographic. On one hand, his character clearly belongs in a specific category, the big talking, good-for-nothing alcoholic parasite, but on the other hand, he is a guy who supports his wife’s dreams and believes that his daughter is capable of defying society’s expectations. He wants more for her than she wants for herself. Yet he is still hampered by masculine gender norms in his unwillingness to confront and wrestle with his own past, which makes him cruel and abusive.

My favorite scene in The Glass Castle is set in the 1980s when Jeannette and her fiancé go to her parents’ latest squat (think Rent, but without the singing) joined by her siblings. Greenfield as the fiancé depicts another interesting male figure who defies gender norms by wanting the smart, complicated, challenging, interesting girl, not a trophy wife, and preferring to plan parties and dinners and decorate his home rather than engage in traditional male egotistical, competitive behavior, but also embraces gender norms by wanting to be financially successful and climbing the social ladder. His character could easily slide into the villain or the victim slot, but he is simply a human being placed in a weird context. He would prefer for Jeannette not to engage with her parents because he sees how they hurt her, and they are a hindrance and embarrassment to his ambition, but more importantly, the entire scene shows how easy it is to be pulled into a destructive family dynamic. He simply becomes a vessel for Jeannette’s rage and battle of wills with her father. It is a hilarious moment in a generally dour film, but also a violation for him. Men may start the wars, but women shame men into physical conflict or adopting negative masculine behavior when the established societal norms suit them. When Jeannette later confesses to her father that she is like him, we already know.

The central question of Cretton’s films is how to live well after a lifetime of trauma without hurting others or yourself. In The Glass Castle, he asks what will make Jeannette unpack her boxes and believe that she is at home. In part, the answer is forgiveness, recalling the positive aspects of the past and knowing who you want to become, but there is a more devastating answer that people seem to miss during the scenes of family laughter during Thanksgiving dinner. People can move on when the cause of that trauma can no longer hurt them, and they can make that trauma into anything that they want, a story, a harmless memory. When trauma can no longer come into a space uninvited, then boxes can be put away. Jeannette heals when she witnesses the death of that trauma. You can live well and be magnanimous after your abuser dies.