World War II understandably overshadows World War I, but with the unfortunate and astonishing reemergence and acceptance of WWII’s enemies’ ideology in the camp of the former Allies, one good side effect is popular media diverting its focus to the less controversial though still senseless losses of World War I. In films like “Wonder Woman” (2017), Peter Jackson’s must see documentary, “They Shall Not Grow Old” (2019), and “1917” (2020), the idea of World War I was reintroduced into the collective consciousness, but the thorny issue of how the British executed its own soldiers for desertion was most popularized in the television series “Downton Abbey” when Mrs. Beryl Patmore (Lesley Nicol) found out that her missing in action nephew, Archie Philpotts, was shot for cowardice and denied any formal recognition for his service. Before that, only one movie, “King and Country” (1964), appears to have addressed this issue. Now there are two.

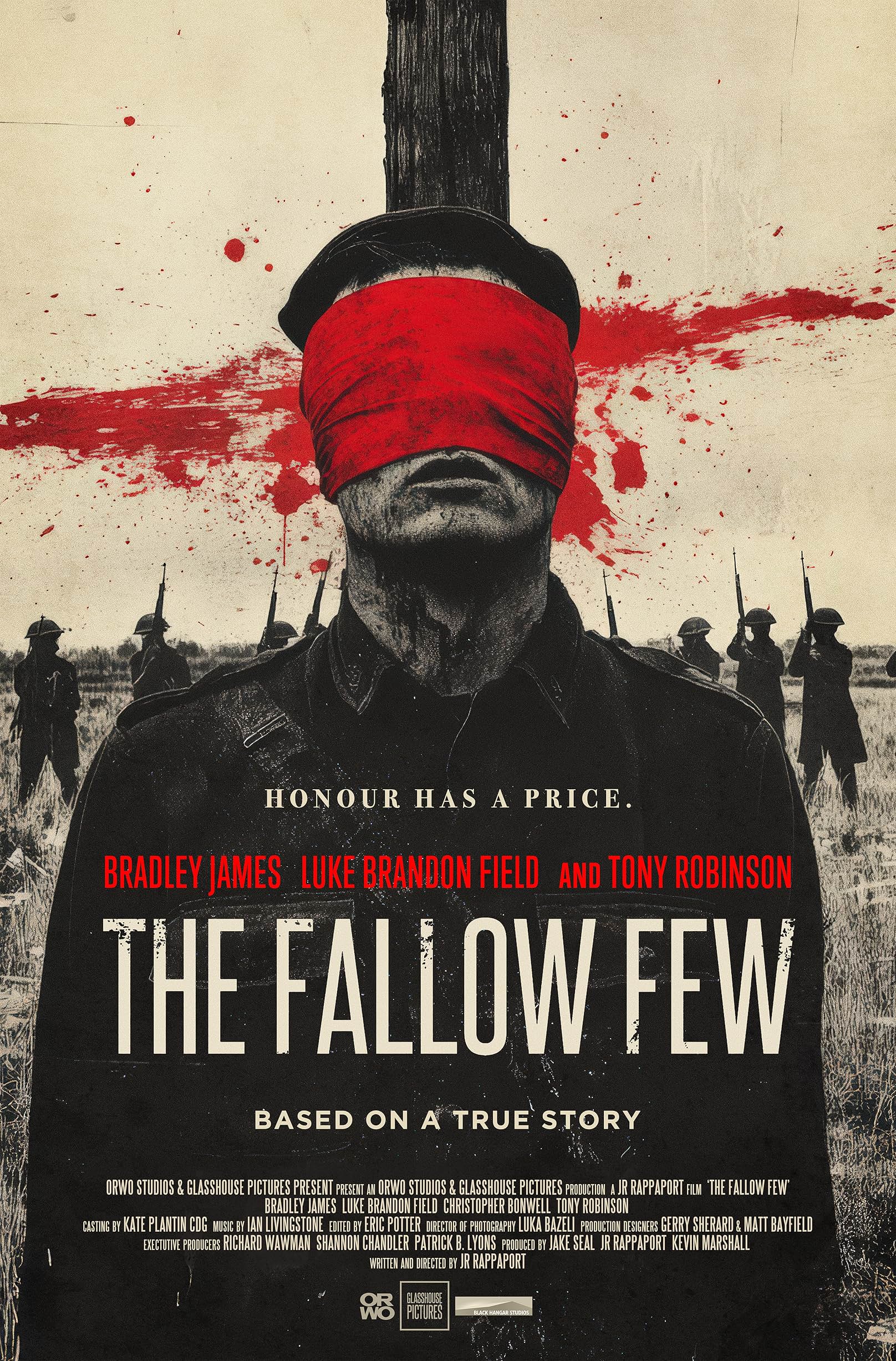

“The Fallow Few” (2025) is a dramatized account of a true story reimaging the night before the execution of Lieutenant Edwin “Eddie” Dyett (Christopher Bonwell) through the eyes of his guards, Corporal George Hansen (Bradley James, King Arthur from “Merlin”), who prefers to be called George and dispense with the formalities. George’s childhood friend, APM Sydney Oakes (Luke Brandon Field), assigned George to the coveted position and safely away from the Western Front. Faced with a moral dilemma, George must decide whether to disobey his superior’s orders and try to get his prisoner a reprieve from a firing squad execution. Will he risk his life for a stranger?

If you are unfamiliar with James’ work, imagine a Nikolaj Coster-Waldau type (Jaime Lannister from “Game of Thrones”) except British, sporting a working-class accent and without a whiff of negative characteristics. As George, James gets forty-five minutes to show George’s gradual deterioration as he realizes the nature of his assignment. James depicts how tortured and conscience-stricken George is as he watches men who look like or may be children before they are executed. Writer and director JR Rappaport in his directorial feature debut could have cut a lot of this sequence and still convey the same message or perhaps spent more time with an average man before jumping to the time lapse sequences.

If Field was wearing a SS uniform, he could have easily been confused for a cinematic depiction of a Nazi: the slow speech, the sly smirk and thanks to Rappaport, the way that the light falls across his face. Being heavy-handed in depicting villains and moral quandaries is forgivable and maybe even required for filmmakers trying to introduce a new fact, concept and dilemma to unfamiliar audiences. While such an approach could be frustrating for historians, cinephiles and more sophisticated viewers, they are not the guaranteed audience, and the goal should be to have the message reach the masses. There is a heavy-handed Rorschach test between how George and Sydney react to a blue butterfly in the cell.

Between Rappaport’s behind-the scenes work and Field’s performance, it is easy to understand Sydney’s villainy and not mistake him for a hero. There is a brief backstory that George used to protect Sydney from bullies, and their accents indicate a class difference with Sydney supposed to be a superior, but the real-life ranking is off kilter because of the physical differences. Sydney wants to even the score and seems to relish snuffing out George’s humanity. He is spending the rest of his life eliminating his weakness by becoming a bully and using the backing of the British Empire’s power to do it without any possible repercussions. Rappaport also throws into Sydney’s speech that he is racist, which unfortunately may win over some people to his side though that was not Rappaport’s intention.

It takes forty-five minutes to get to the meat of “The Fallow Few,” i.e. for an officer to land on the chopping block. Bonwell has a hard job because though sympathetic, Eddie is not a great guy. School boy rules and rivalries still govern Eddie’s attitudes and conduct thus continuing a rivalry with an Eaton enemy, John Herring (Oliver Norman), with severe backlash leading to his arrival in that cell. Bonwell manages not to pull punches on his character’s ugliness and emphasizes it so as not to put a thumb on the scale in his favor. Bonwell goes through a range of complex, nuanced emotions from stiff upper lip to increasing shakiness.

Tony Robinson as Canon F.G. Scott is a scene stealer as the clerical Obi-Wan Kenobi, i.e. Eddie’s only hope. Part cleric and all amateur legal counsel, Robinson’s brief appearances are memorable and punctuated with a flourish that do not seem over the top given the circumstances. This character introduces the possibility of “shellshock,” which is now diagnosed as post traumatic syndrome disorder (PTSD), which can be considered a service-connected disability that can now make a veteran eligible for disability benefits in the US. The stigma of mental health disabilities plays a pivotal role because of Eddie’s class and family profession, but even today, people who also earned the right for their country to pay them back are reluctant to accept the benefit under less dire circumstances.

Most of “The Fallow Few” unfolds in the capacious cell so the only variation is who walks through the door, which is the reason that Robinson is such a breath of fresh air. As the only person not subject to the same rules and risks, he brings a cheeriness otherwise missing in the oppressive environment. Even though the building is alleged to be a former post office, the hallway has a stained-glass window and appears more like a church.

Because of the single location, could “The Fallow Few” be a play? Absolutely not. It is cinematic though perhaps to a fault thus the earlier comment about needing a bit more editing. There are lots of scenes where concepts are explained through visual vocabulary. For example, George, his subordinate and Eddie share a brief, last hurrah, and the camera movement and editing communicate the emotion of that moment whereas laughing, smoking and drinking on stage would be flat. Why did there need to be several close ups of a discarded can of food? No idea, and no one is perfect.

“The Fallow Few” is not visually violent, but emotionally graphic. Though cutting a half hour of fat could have helped make the movie stronger, as a first film on a little-known topic, such excesses may actually help ease moviegoers’ orientation to an unfamiliar time, place and contextual values. The good news is after WWI, the British did not execute soldiers for desertion, and Dyer got posthumously pardoned in 2006. If you are interested in separating fact from fiction in Dyett’s tragic story, Leonard Sellers recently wrote a book called “Death for Desertion: The Story of the Court Martial & Execution of Sub Lt Edwin Dyett” (2003). His story is alleged to influence A.P. Herbert’s novel, “The Secret Battle” (1919).