I actually remember seeing the preview for The Clan and being impressed by the visual contrast in a long tracking shot between the joviality and warmth of the family with the sinister homemade dungeon nearby. It communicated the dissonance that it was possible for violence and the family hearth to exist in the same space, and that the same people could be capable of such things. I never forgot it, but I don’t think that this movie was ever released in a theater near me, or if it was, it wasn’t for long because I missed it, and I definitely wanted to see it. It gave me the same chills as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre with less gore, but the same vibe of a demented community agreeing to appear normal, but conduct awful acts while retaining family unity.

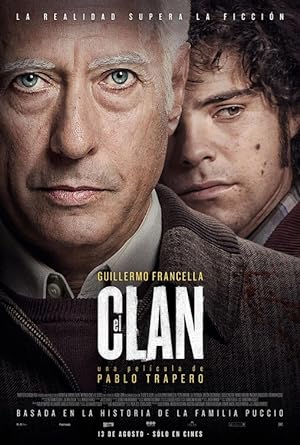

I finally got to see The Clan and was surprised that this atmosphere was not emphasized in the way that I thought it would be. It was not a horror movie or a thriller, but a biopic of an actual Argentine family, the Puccios, with more in common to I’m Not Scared or All the Money in the World. In spite of being more educated than the average American, I still don’t know a lot about my neighbors in the south, South America that is, and I kept confusing Argentina’s history with Chile with all the references to the disappeared and a shadowy military government giving way to democracy.

The Clan is not here to catch you up with what you’ve missed, and normally I watch foreign films without being concerned about what I bring to the table, but it is crucial to enjoying this movie. So you’re left with three choices. Spoil the movie for yourself so when you watch it, you will understand the subtle changes on screen that actually communicate a tremendous amount of information. Don’t spoil the movie, be vaguely disappointed then afterwards realize that maybe it was actually a great movie, but you were clueless. Don’t bother to watch the movie at all.

Before discussing The Clan, I’m going to spoil the movie by providing information that I wish that I knew before discussing my thoughts on what I did understand when I was watching it. Argentina was under military rule, which gave way to democracy. The Puccio patriarch used to work for the state’s intelligence service allegedly kidnapping communist guerrilla fighters. With regime change, he becomes a proprietor of a small shop, but decides to kidnap rich people that his son, who is a famous rugby player, knows. The Puccio patriarch’s accomplices are not just his family or friends, but include other men whom we don’t know anything about. Maybe the government similarly employed them in the past, but it is never explicitly told. While the people who are kidnapped never expect it, it seems to be an open secret. Average people offer them targets to extort money from.

There is a lot of unspoken, but thickly implied class resentment between former government employees or former associates or servants of the rich people and the rich people that are kidnapped. For people who used to kidnap communists, they really seem to favor the redistribution of wealth from the rich to the former spook wing of the government. There is a resentment and envy that the wealthy get to enjoy the fruits of their labor, the blood on their hand. The government seems to know what is up and is willing to tolerate it to a point then cracks down on the kidnappers when they attract too much attention in the press, perhaps because of a violation of gender norms. The Clan shows a tertiary character that got caught before the Puccios who explictly says that the jig is up. There is a visual complicitness in the way that the government finally stops the Puccio family that conveys more than finally getting what they deserve, but that the techniques are so similar, and there is such a disregard for humanity as part of procedure that they have to be related. When the government interrogates the Puccio patriarch, who claims that he was working for the government, even though I’m generally inclined not to believe any bad guy who regularly kidnaps and kills his victims, the movie seems not to dismiss it as the ravings of a madman. The (unseen?) figure of the Commodore seems to loom in the background, but I have no idea who he was in the old or new government or if he was really involved and tacitly approved, but I wish that I knew more because it seemed germane to the plot. Are they fall guys or independent contractors?

As a viewer, it is important to be able to independently gauge the credibility of the characters on screen, but with The Clan, I am clueless. So many plot points got lost in translation. Why was the music in English instead of Spanish since the singers used were not the ones who made the featured songs famous? I did not understand that as their crimes got more brutal, their store also transformed and began to cater to more affluent clientele. I thought the famous kid worked at a different store than the one that the father owned or it was the kid’s store purchased with blood money from the ransom money. No, it was the same store. While I understood why the Puccio kids would leave the nest and not come back, I did not understand the logistics of how they were able to leave the country so easily and not come back. Was this phenomenon emblematic for Argentinians—losing the youth—or Puccio specific? Do you have to leave the country to escape your father’s reach if he is the government?

I did think, perhaps mistakenly, that The Clan was trying to convey to audiences that when the government violates its citizens’ dignity with violence and abuse, the government is made of men with families and homes, and these men act similarly at home. There are signs that the Puccio patriarch is a nationalist. He is offended that his son left the country, not because of loss of contact, but as a betrayal to the country. Sports may play a smaller role, but is part of this spectrum of pride in something that you may or may not have contributed anything to. His son is the poster boy of this pride, but not permitted to take pride in his individual accomplishments. The father absorbs his son’s life into his own. For a nationalist, his family does not consist of sovereign individuals whom you want the best for, but they are useful tools in service to the government, and since he sees himself as the government, they exist to please him. There is an unspoken danger in two words: my kids.

The Puccio clan seems shockingly well adjusted for the majority of the movie though there were signs of psychological strain. Kids generally don’t run away from home and never come home without a reason. Also a father who manipulates his son into faking his own kidnapping then killing his friends is causing trauma even if the son intellectually knows that he isn’t being kidnapped. By killing his friends, he is also killing his son’s ability to be independent from the family. You can’t bond with the outside world if your dad has the power to erase it, and if he can murder with impunity, then his control over the family is absolute. There is no one to appeal to. Also by being complicit in crimes, it destroys your future, your ability to think that there is a life and way to provide for yourself and your family outside of the family business. Sure he could have refused and run away or reported his dad, and he should be held responsible, but could he?

The Puccio patriarch says that he does everything for his family, but as his schemes start to fall apart, he becomes more psychologically abusive with his son, and when he has a chance to spare his family pain, he chooses pride and himself. The fact that once the government does intervene and split apart the family, the entire family stays away from him indicates that the movie probably got it wrong. The following is complete conjecture, but he probably was physically and psychologically abusive to his entire family. I am not equating Nazis during WWII and those who participated in the Argentinian military dictatorship because I don’t know anything about the latter, but many people need to be reminded that after WWII when no one can get sent to the gas chambers, people turned on their neighbors and abused their family. If you are from the Antebellum South, if you don’t have slaves to beat, you beat anyone else. There always will be an outlet for state sanctioned violence because that violence originated in the hearts of those that made the state complicit in their demented thinking, and in the absence of a sanctioned target or the veneer of authority, that violence will erupt closer to home.

Too much was lost in translation to say that I enjoyed The Clan, but I appreciated elements of it despite my confusion. I would not recommend it if you don’t know a lot about Argentinian history because it is more than a crime drama thriller. I did admire the unflinching and shocking denouement. I definitely suspect that it is a masterpiece even if I don’t get it.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.