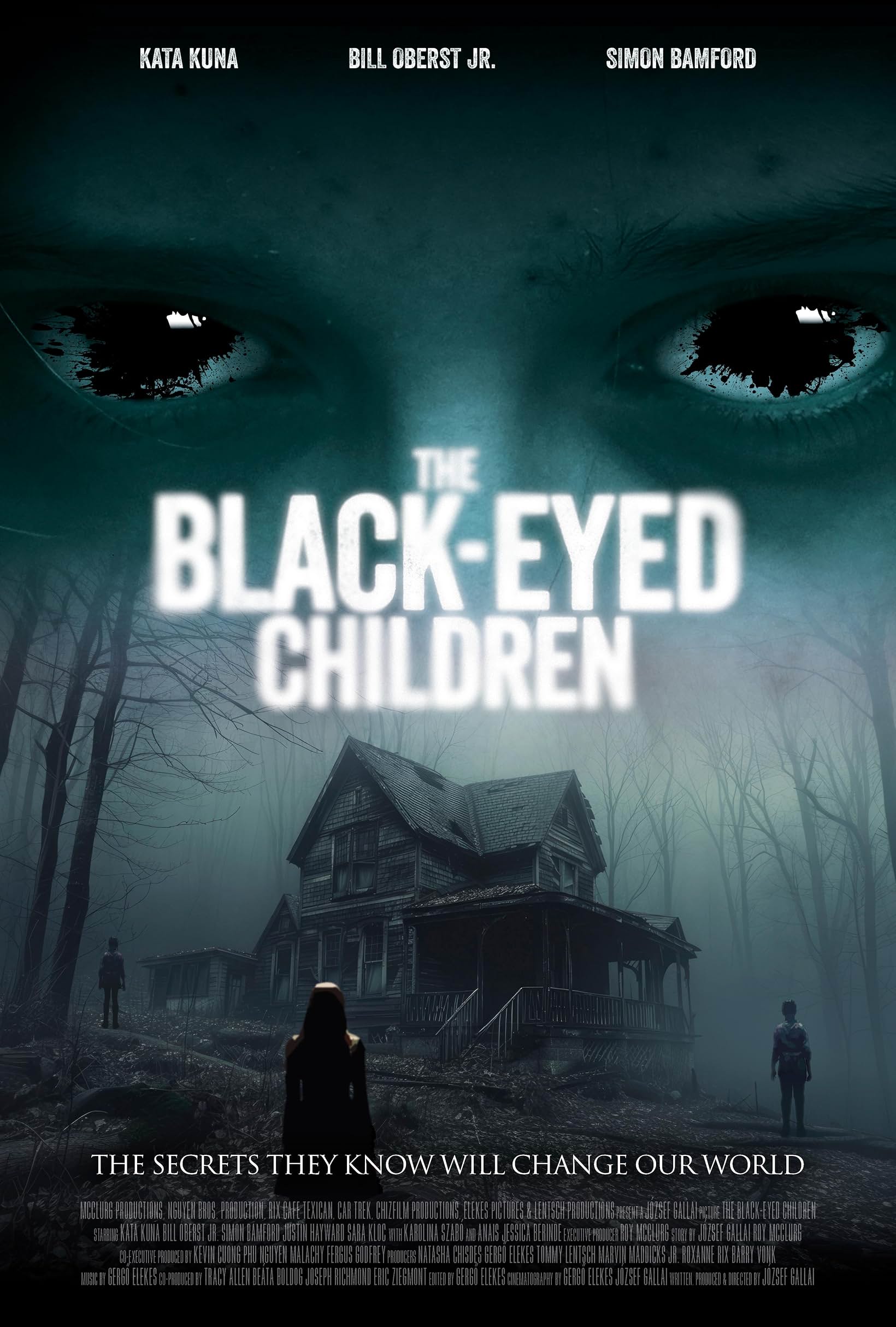

Director and cowriter József Gallai’s latest film, “The Black-Eyed Children” (2025) is short, but not sweet. Fifteen years ago, seventeen children disappeared from Camp St. Beatrice in Sunriver, Oregon. Today, Claire Russell (Kata Kuna), a child psychology student from Oregon Health and Science University accepts an offer to be a camp counselor unaware of the camp’s history. When she arrives, the place seems abandoned until a few children who admire John Carpenter’s staging line up and watch her from a distance. As night falls, they get closer. Does Claire know what happened?

“The Black-Eyed Children” rests squarely on Kuna’s shoulders. It may be the story, or it could be the performance, but she did not have what it takes to carry the entire story or make it better. The role requires a more experienced, unreasonably excellent actor beyond what a low-budget indie could afford. Anyone would find it challenging to act for most of the movie without anyone to play against. Though better than the average cat, Claire seems stupid when she gets nauseous and pukes on her wooden floor instead of looking for a waste basket or running to the bathroom, which would take her out of the camera’s range. When she arrives at the camp, it makes sense that she would explore the buildings, but not that she would park herself in one of the rooms instead of immediately wandering outside. She talks to herself a lot, but in a very basic way. With so many children’s drawings strewn about, it was a missed opportunity for Claire to show her personality and expertise because she could have analyzed the pictures and theorized what happened. It is especially annoying to have a character who explicitly references horror movies yet acts as if she has never seen one.

“The Black-Eyed Children” has found footage elements but is a conventional horror movie with the backdrop being an investigation that the Man in Black (Gallai) leads. There are numerous sweeping shots of the grounds around the camp, which is autumnal and still. These shots are the best aspect of this film. The footage consists of video recordings that Claire shot, cassette recordings of frantic parents calling the cops or recordings of telephone conversations between Claire and a group of people with connections to the camp and a video message from the camp’s founder and director, Mr. Donahue (Bill Oberst, Jr.,).

The most interesting part of “The Black-Eyed Children” is the camp and what happened there. The recordings detail what the family members discovered, and the cassette player is doing all the heavy lifting to help the audience understand how Claire fits into the big picture. If you are expecting the film to adhere to the legend of the titular creepypasta folklore, adjust your expectations. During Claire’s drive to the camp, the radio broadcast offers some clues, which overlap with when Claire got sick at home before the trip. The best shot is of the sky over the camp. When it gets into specifics, such as notebooks containing sketches, broad scribbles and a memory card, it is more atmosphere than answers. It is specific enough to adhere to the legends, but vague enough to be unsatisfying. Why this camp? Why Claire and these kids? It is all very otherworldly in a brand name way like before “The X-Files” gave any solid information until it info dumped in the director’s cut of the first movie once Chris Carter recognized that the charade can only go on for so long. It is all a lot of talk, not showing, and at some point, as the expectation for a payoff wanes, any investment in the story evaporates.

At the eleventh hour, there are some answers and a shameless dry begging to return for the sequel. It is more interesting than the entire movie, but it is too little, too late. If more time was devoted to the investigation about the camp, then less time would be devoted to Claire just freaking out and being ineffective in saving herself. Even with these answers, it does not make the story more interesting but just acts as a gateway to more stringing along. While Oberst makes nothing sound like something, it is still more telling than showing. The showing is insufficient. The big mistake may be Gallai and cowriter Roy McClurg Jr.’s decision to conflate missing children with the black-eyed children. While the implicit exploitation of already vulnerable children is a worthy beat to include in the film, it feels integral to the human horror that is related to the phenomenon but not central to it. Claire is the key to finding out what happened to the missing children, but the key is boring, and the door it opens is not as tantalizing as it is to the characters in the film. It feels like an exercise in sunk cost fallacy to keep going.

The writers deserve credit for trying to explore a recent urban legend, but there are plenty of films that have tried and failed to turn into wild fire hits, including “Black Eyed Kids” (1999), “The Black-Eyed Children” (2011), “Sunshine Girl and the Hunt for Black-Eyed Kids” (2012), an alleged MSN’s Weekly Strange February 2013 episode 11, and “Black Eyed Children: Let Me In” (2015). After watching Gallai’s take, I’m not eager to check out the rest.

One of the radio broadcast announcements talks about a likely fictional film award which references a film called Hermit about Christopher Thomas Knight, a real-life figure who lived in Maine for twenty-seven years and was the subject of Michael Finkel’s nonfiction book, “The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit” and a 2022 documentary with the same name. It feels like a clue to the inspiration of Gallai’s prior found footage film, “A Stranger in the Woods” (2024), which is amazing and the opposite of this film.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

So the kids found a gateway in the woods, and exposure to it changes them on a cellular level, thus the eyes, which enables them to be transported to a different dimension. For reasons unarticulated, people believe that access to this gateway is important. There is a promising potential story about the affluent using vulnerable children to gain access to the mysteries of life without caring about the impact on those kids, but the exploitation is not the point. Instead, once Claire stops resisting, it is as if oblivion is the home that these children and Claire could not find on Earth. Aliens make the best adopted parents. There is some time travel, Bermuda triangle vibes, but it feels inconsistent with other elements of the story, namely the Man in Black, who could have more in common with Claire though why would he take orders from some random human rich dude? If I could control time and space, I’m not working for someone who does not. I would have standards. Considering that a lot of the parents miss their kids and fellow camp kids turned adults seem happy with their parents, this result seems unearned. “The Black-Eyed Children” is all atmosphere, all sizzle, no steak. Damn good meteor shower. I don’t care if part one is just a set up. “It” (2017) was better than “It: Chapter Two” (2019). Each film must stand on its own and work together collectively.