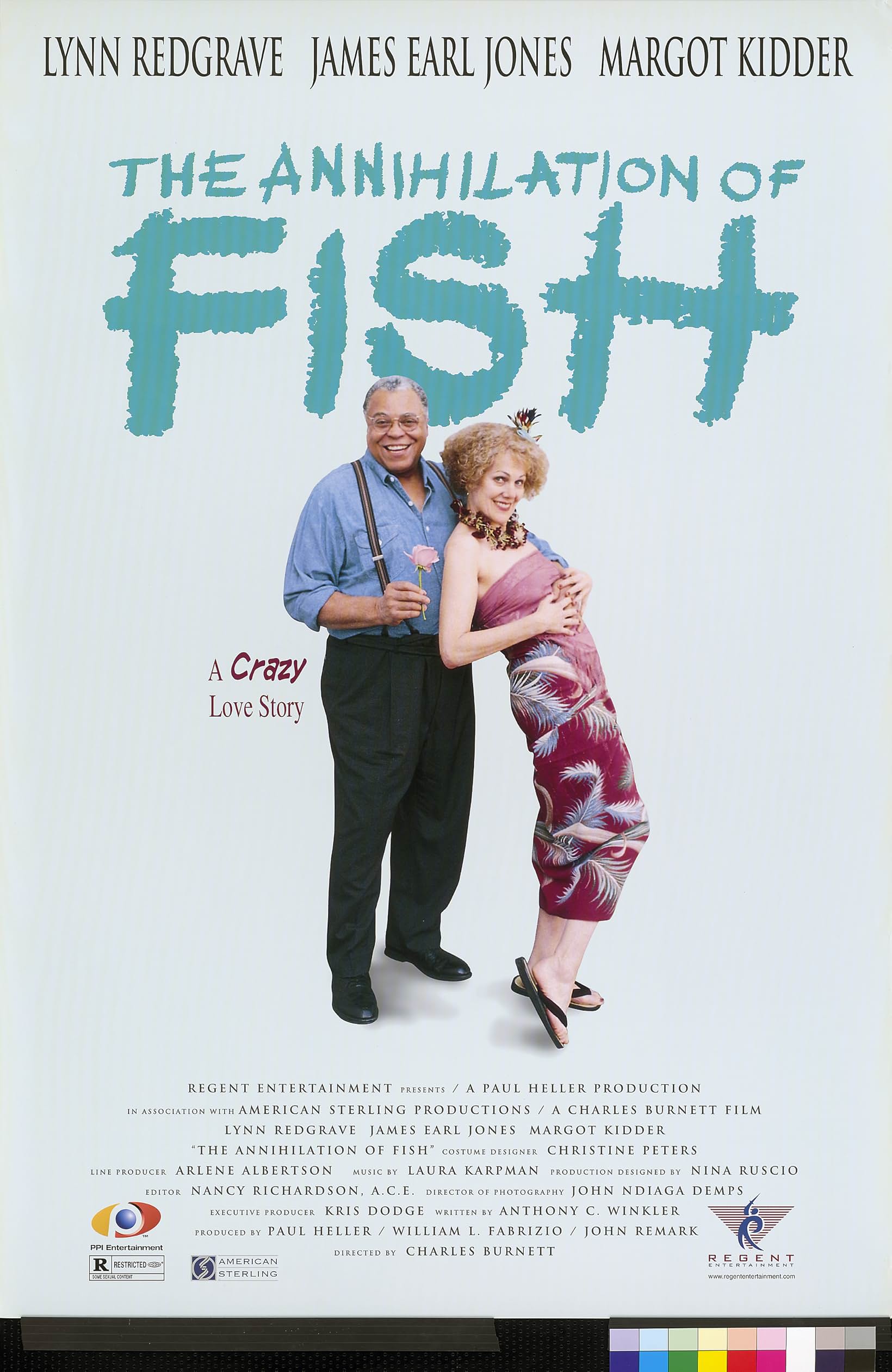

The nineties may have been the last cinematic era where characters could be flawed and strange without being cute, quirky and safe. Somewhere along the line, the latter became aspirational and aesthetically pleasing thus as unattainable and unrealistic as becoming Barbie. “The Annihilation of Fish” (1999) revolves around three people who somehow make a community despite their peculiar, fixed ideas about how they navigate the world, and two of them become romantically entwined despite their rough first meeting. Obadian Johnson, aka Fish (the late, great legend James Earl Jones), wrestles a demon named Hank. Flower Cummings, aka Poinsettia (British Lynn Redgrave, Weight Watchers spokeswoman in red with the long legs and part of a grand family of generations of actors, which includes Vanessa), is living in sin with Giacomo Puccini, the Italian composer of “Madama Butterfly” (1904). Mrs. Muldroone (Margot Kidder), a Southern widow who tends a great weed on the grounds of her Los Angeles rooming house, is tolerant of their quirks.

Director Charles Burnett and writer Anthony C. Winkler craft a poignant story that asks whether everyone deserves love and acceptance, i.e. a home, a romantic relationship, admittance to public spaces and communities. The answer is yes. When they introduce Fish, he is at a Harlem church when he engages in one of his wrestling matches, which seems like the ideal place to wrestle a spiritual entity, but no, Jacob restricted that activity to the outdoors. His version of wrestling involves accidentally grabbing a fellow parishioner’s leg, so the prohibition is reasonable. Burnett and Winkler initially depict Poinsettia at the aforementioned opera in a San Francisco open air venue annoying the performers and fellow opera lovers alike with her singing and ongoing flirty banter with her non-corporeal lover. In some ways, Poinsettia has the advantage or disadvantage because when she chooses, she has a perspicacious enough eye that she can tell when she is in danger, or someone is more out there than she is.

Burnett devotes time to showing how people react to them in the first act of “The Annihilation of Fish.” Winkler offers no hints how Fish and Poinsettia can financially survive without working and being social outcasts that no one wants around them. By showing them in spaces for people in a certain socio-economic bracket (Greyhound buses and stations, thrift stores and furnished apartments), Burnett shows how humble their prospects are and how limited people’s forbearance will be. Mrs. Muldroome’s home becomes a place where they can be themselves. Most landlords and fellow tenants would not be tolerant of any one of these characters’ behavior, and even in a movie as gentle and warm as this one, a tenuous tolerance is the most that one could hope for.

“The Annihilation of Fish” is a delight in the way that it depicts Fish and Poinsettia deciding to start a new life, move and care for their belongings. Each makes the space their own, cleans and settles in. These nesting pursuits are universal and humanizes them after their less relatable introduction. Mrs. Muldroone may be the strangest of them all because she accepts Fish and Poinsettia at face value instead of challenging their beliefs about themselves, their imaginary friends and their right to inhabit their homes. Between you and me, I wish that Mrs. Muldroone and Fish got together over Poinsettia and Fish, but it is not a criticism of the story, just a preference. Kidder is almost unrecognizable with her seamless performance. If Blanche Devereaux skipped her sister’s home and headed straight to Mrs. Muldroone’s house, Blanche could have lived a better life.

As “The Annihilation of Fish” unfolds, Burnett and Winkler reveal that they are alone in the world and not too thrilled about it. Fish is at sea without a purpose. He suffers from the fatal capitalist mindset that being useful is the rent that people pay for the right to exist. Without feeling like a prose dump, each person adapts to the other, forms new habits which ameliorate their most off-putting qualities and reveals their back story without feeling heavy-handed. There is a catch. Fish notices the change in his life and has difficulty reconciling it with his obligation to keep the world safe from demons, but Poinsettia is determined to hold on to her newfound love and not return to canoodling with a phantom.

“The Annihilation of Fish” probably takes place sometime after 1981 when the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 passed Congress and repealed most of the provisions of the Mental Health Systems Act of 1980. It was seen as a continuation of Ronald Reagan’s legacy as governor of California with the passage of the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act to deinstitutionalize mental health treatment, which sounds good in theory but led to rampant homelessness and zero resources for treatment once no longer committed Burnett and Winkler’s story is the gentlest vision of what life could be like for people if the government and other social safety nets failed to catch them. Now most urban spaces in the US are not affordable for the most functional, acceptable members of society. Maybe movies are no longer made like this one because these conditions no longer exist anymore.

“The Annihilation of Fish” has subtle notes of magical realism that are easier to miss on the small screen so if you have an opportunity to see it on the big screen, do so. It may remind some of Kathleen Collins’ “The Cruz Brothers and Miss Malloy” (1980). Hank may not be visible, but he has physical effect on the world-rustling trees, destroying art. The camera represents his point of view, possibly an inspiration for Steven Soderbergh’s “Presence” (2025)—Soderbergh contributed financially to the restoration of this film. At the beginning of the movie, Fish gives a matchstick Noah’s ark model to a neighbor at his former home and spends the rest of the movie trying to recreate a replacement. At one point, the seemingly complete model spontaneously combusts, damaging the newspaper underneath it and stops short of spreading and destroying the place. What does it mean? The association is with the phrase that James Baldwin popularized with his novel title, “No more water, the fire next time,” but here it feels like a sign that Hank is alive and well, but the none of the characters and nothing in the narrative points to that interpretation. The model seems tied to Fish’s health, his will to live. It is also a gift that he awards anyone who made his dwelling a home, and it may not be able to stand until he is ready to move on. It is an easily forgotten note in a memorable movie. There is also a spiritual mythology about guns, the US, the NRA, demons and dreams, which would probably get the movie cancelled all over again even though it predates mass shootings as a quotidian part of the day.

Ultimately “The Annihilation of Fish” is still a sweet, utopian and revolutionary film for the way that it treats older people who may suffer from mental health issues. The story does not rest on making sly fun of them and does not insult its audience like movies such as “The Leisure Seeker” (2007), “Poms” (2019) and “80 for Brady” (2023). They are older people with normal, quiet lives, not an oversized exaggeration resting on superficial, exaggerated consumption and commercialism. Very few films feature sex scenes that expand the story and relationship but are thinly disguised ways to fantasize about having sex with a beautiful celebrity purely for titillation purposes and otherwise stops all momentum in its tracks for ogling. This film offers an honest, intimate depiction of two people becoming one. It is a true love story.