Pedro Almodovar is one of the greatest living film directors, the rightful heir to Hitchcock’s throne with his mix of psychosexual driven dramas and an innovative storyteller who delivers uniquely crafted narratives. When Hulu notified me that his films were going to expire and be removed on June 20, 2017, I decided to watch all his films, including the ones that I already saw. This review is the fifth in a summer series that reflect on his films and contains spoilers.

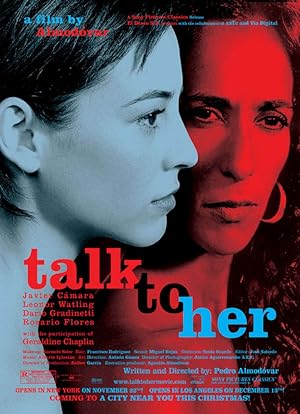

Talk To Her may be one of Almodovar’s most controversial films. I saw it in theaters when it came out in 2003, and over fourteen years later, after streaming it, it is no less shocking. Before seeing Talk To Her, if you can get access to and watch an excellent documentary called Pina, which shows more of the dances featured in Almodovar’s film, then do so. The film is a twisted tale of friendship and obsession between two men.

Benigno is a tireless, devoted and caring nurse to Alicia, a coma patient and former dancer. He helps his coworkers and befriends fellow visiting devotees. Marco is a sensitive and sympathetic journalist whose bullfighting girlfriend, Lydia, is in a coma in the same hospital. They become friends, and Marco kind of gets to know Alicia(’s breasts) by hanging out with Benigno when he cares for her. As the film unfolds, we discover that Benigno actually fucking stalked his patient before she got sick, got the job as a nurse when she fell into the coma and was raping her. Also if his mom is dead, who is he talking to in his apartment? Norman Bates called and hopes that you didn’t keep her body in a rocking chair. No one would know if Alicia didn’t get pregnant, but it all works out because after the pregnancy, the baby is still born, Alicia awakens, Benigno kills himself, Alicia accidentally meets Marco, and sparks fly!

Except it never genuinely felt like a happy ending to me because I know why Marco is attracted to Alicia, but will Alicia still be into Marco after she finds out what happened: that Marco was a friend of her rapist, and that he saw her partially naked while she was in a coma! Alicia was some weirdo’s living, breathing sex doll, and Marco hung out with him. Sure Marco discouraged Benigno’s fantasies, but once he found out what happened, he remained his unconditional friend, which is totally fine if you feel led to do that because even pervs need love too, but I’m not sure if Alicia will be so understanding. The movie ends too early! It is just the beginning of a whole new nightmare, and one of Almodovar’s few narrative missteps in an otherwise perfect career. Romance ain’t going to polish this turd. All’s well that ends well, but this isn’t ending well.

Intellectually I understand what Almodovar was trying to do, and he kind of succeeds. Talk To Her is like Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. These two men are not in authentic relationships with the women in their lives, but living in a fantasy world; however it only becomes obvious in Benigno’s case. Marco thought that he and Lydia were in a relationship, but she was not into him. This information comes from her alleged ex, but sounds plausible since she remarks before her final appearance in the ring and in a flashback that Marco did all the talking. These men love the idea of women, but are not too great at actually interacting with real, functioning women. This movie takes the idea of artists as the preferred priests for society to a demented level-these performing artists will never repeat these secrets because they can’t hear the confessions. Benigno provides a cautionary tale to Marco as Lucia did for Pepa. Unlike Benigno, he can stop attending to a comatose woman and live in the real world.

When Marco enters the real world however, he makes Benigo’s fantasies come true. Marco lives in Benigno’s apartment after Benigno redecorated it to look like a catalogue. He spies on Alicia in the dance studio from Benigno’s apartment. He then encounters Alicia during an intermission at a dance performance, and Almodovar’s scene title makes it clear that this is the beginning of Marco and Alicia’s story. Usually when Almodovar empathizes with a madman, he effectively and simultaneously refutes the madman’s fantasies by reflecting its effect on the victim. He succeeds at making us sympathize with Benigno while being horrified by his actions. Talk To Her does show Alicia’s fear of Benigno and clearly does not condone Benigno’s actions, but by showing Benigno’s dream come true with another problematic character, Almodovar is still vindicating his fantasy. It feels closer to Anne Rice’s take on Sleeping Beauty, which I never read, than a genuine happy ending. Rape becomes a plot twist to get closer to a happy ending for Marco, and Alicia’s lack of full access to her story when she was in a coma feels like a continuation of that violation. It is the polar opposite of the lesson learned in All About My Mother though Talk To Her shares the same impulse of transforming pain into a new life through a new relationship, but fails. It is creepy AF.

Unlike most of Almodovar’s films, Talk To Her does not focus on creators, but consumers, his audience. Even though this film starts like most of his films, with an element of confusion and some type of performance, the characters do not create, but digest, appreciate then regurgitate their experience for someone else’s imagined pleasure. Because they cannot create, their madness is their escalation of their voyeuristic viewing experiences (Benigno from his window looking at Alicia as she dances and Marco as a tv viewer watching her interview) to puncture the fourth wall to be a part of the creation. Even when they successfully enter this world, they can’t understand it. There is a comedic scene where Benigno tries to have a creative conversation with Alicia’s ballet instructor, Katerina, and utterly fails to get it.

Talk To Her does suggest that it is harder for women who create than their male counterparts. Their cis male consumers are overwhelmed by their attraction to the performer than any interest in the actual performance. There is a brief cameo by two of the main actresses from All About My Mother during a singing performance, and they never speak or appear again. Almodovar seems to be implicitly critiquing his cis male viewers need to possess what they admire by contrasting the two main characters with this cameo. These two women can appreciate and be emotionally overwhelmed by a performance while retaining their identity or losing their dignity/sanity. Marco later realizes that his memories and his consumption miss the mark. He is not correctly receiving the messages as intended. Almodovar is interested in the logistics of poor communication. In this film, it is embodied by partition glass, microphones and speaking through phones to a person that is right in front of you. It reminded me of similar frustrating attempts at communication in Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown when the receptionist speaks into a microphone at the person in front of her.

Talk To Her is one of Almodovar’s few films where the medical profession fails. Usually medical professionals are seen as allies or effective protectors in films like Law of Desire and All About My Mother, but in this film, they either fail (Alicia’s father is a psychiatrist who professionally treated Benigno, but fails to diagnose his pathology) or violate their duty to their patient (Benigno rapes the comatose Alicia while working as her nurse). Perhaps Almodovar agrees with my assessment of the ending and made The Skin I Live In as an unofficial sequel to this film.

Talk To Her is also one of Almodovar’s few films without a trans or gay character or explicit sexual situations except for a surreal fictional silent film. Benigno pretends to be gay to secure his access to Alicia, but is not. There are actually women, mainly coworkers, who are interested in him. He sees himself as an ally to women, but is the opposite. He may present as more harmless than Banderas’ character in Law of Desire, and Angel and the priest in Bad Education, but he is more sinister because even after he is stopped, he retains a type of innocent insanity.

Talk To Her is a flawed and problematic, but memorable portrait of unlikely empathy and friendship.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.