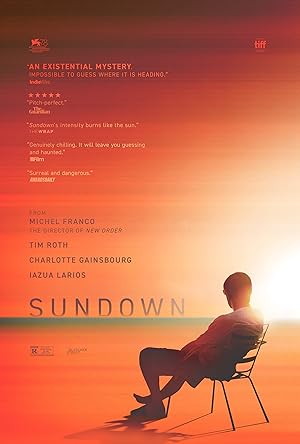

“Sundown” (2022) stars Tim Roth as Neil, a man on vacation with his family. When they go home, he stays behind, and the consequences affect the family forever. Michel Franco wrote and director. It is Franco’s second collaboration with Roth after “Chronic” (2015).

When I saw the preview for “Sundown,” while I enjoy watching sad white people on vacation, I had no interest in paying to see it in theaters. The preview gave me the impression that Neil was going to cheat on his wife, and the matter would escalate because of drama involving money and violence. I also was concerned that it would be one of those films that exoticized how brown people really know how to live, and Neil would finally find himself by abandoning everything. While I enjoy Roth’s artistry, he gets typecast as a villain, and I have seen plenty of those movies: “Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead” (1990), “Reservoir Dogs” (1992), “Pulp Fiction” (1994), “Rob Roy” (1995), “Planet of the Apes” (2001), “The Musketeer” (2001), “The Incredible Hulk” (2008) and many more. I was just over it.

The pleasure of “Sundown” is realizing how wrong our impressions are and how inscrutable everything is even as more gets revealed. While watching the film feels intimate, and it is easy to forget that you are watching a movie, not a life, unfold, even with well-known actors such as Roth and Charlotte Gainsbourg. Franco jolts us and his protagonist out of our respective reveries with punctuations of emotional and physical violence while capturing ordinary vacationing activities. It feels as if Franco’s film is saying something about the nature of life and film that are contradictory. Film can reveal more about a person than life and alternate between capturing and sensationalizing it in a way that does not happen, but there is still a gap of understanding among people, even viewers and characters, in film and life.

I had some reservations about the violence because of American stereotypes about Mexican people. Once I found out that Franco is a Mexican director, my concerns were somewhat alleviated, but in his prior movie, “New Order” (2020), some suggested a socioeconomic racial prejudice. He apologized while claiming that he was suffering from “reverse racism,” which is not a good sign because it does not exist. I will defer to Mexican viewers regarding whether his depiction of his country and fellow countrymen is accurate, or if he is vying for a spot on their version of FOX News.

“Sundown” is one of the best films in 2022 to date. I regret not seeing it in theaters on the big screen because the best part of this movie is how Franco shows and never tells. There is no prose dumping so the film requires viewers to pay attention. The advantage of watching the film at home is the ability to pause, rewind and rewatch.

Context clues imply early that this family is wealthy. Franco sets Neil apart from the rest of the family in each frame. Gainsbourg’s character is the unavailable one though present with the family. She leaves rooms, checks her cell, protests playing games and displays an immediate emotional brittleness with the introduction of stressors. In contrast, Roth depicts Neil as a man emotionally present, still, passive, and silent. He lacks capacity to sustain engagement with others and withdraws, but the movie’s question is why. Early flashes and the denouement provide some answers, but the ambiguous ending indicates a man also running away from himself. Does Neil understand himself? It is almost as if Franco decided to create a character whose external behavior is objectively inappropriate but will make him relatable to the viewer despite his selfishness and cluelessness and make the supporting characters stay where we were, horrified at his conduct.

Neil’s silence, a refusal to explain himself, while trying to communicate his feelings towards others makes “Sundown” a riveting character study. Neil knows how his actions will be perceived but refuses to change course. He comforts with limits. To show that he is not just going through the motions, he takes actions with concrete consequences. He is a man who chooses to opt out and understands the level of discomfort he is inflicting on others and disapproval that he will receive. When he does talk, he is oblivious to his privilege. He is a man used to people taking care of things for him and not having ulterior motives. At his most animated, he encourages a woman to travel without considering whether she can afford it. His privilege does not make him spoiled. You can sit him down anywhere, and he will stay there forever. The catalyst for his running away appears to be strong, negative emotions related to grief. He rejects them. Roth does a superb job embodying his character, especially considering that he usually plays more dynamic villains.

Like “The Lost Daughter” (2021), there is a pleasure in seeing someone choose themselves first and living life, but unlike that film, Franco restricts us to a specific moment in time except for surreal flashes that hint at the origins of Neil’s ennui. There is one early scene at dinner with the family when Roth glances from the waiter to the plate displaying meal options. Franco entices us with images of pleasure for us to vicariously enjoy mingled with death. Franco mainly focuses on Neil then shows us how Neil sees the world: a cluster of fish drowning in air for our pleasure, lime juice sprayed on shellfish that makes its garnish move, the fish head and bones left after a recent repast, blood mingling in sand while waves wash it away.

While some reviewers suggest a correlation between an original sin of wealth and death, this film does not make any distinctions except that wealth adds a layer of protection from death and life, i.e. contact with people and spontaneity instead of control, but not immunity. Death comes suddenly regardless of species or class, but Neil’s attention is drawn to it. He notices it more than others. People notice his preoccupation and distance, but attribute it to other reasons: not caring, sleepy, etc. He is attuned to another present reality which has a rational explanation but explains how he can be more present than others to his surroundings while seeming distant. He becomes more vulnerable to that reality as the outside world disrupts his attempts to just enjoy life. When the film has surreal moments that still fit the film’s logic, it is a signal that Neil no longer distinguishes the destiny of men and animals, but he refrains from confiding his visions to anyone else.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Like an animal that runs away from home to die alone, “Sundown” shows what that would look like for a human being. There is a brief time when Neil diverts himself with the simple pleasures of life such as being in water, which results in him getting involved with other human beings socially, including romantically. To his horror, he discovers that those connections collide him with what he is trying to avoid: witnessing other people become inconsolable about his impending death and having to dwell on it. When he lands in jail, he is concerned about Berenice, but when she cries over him, he flees from her without a second thought just as he did with his family. He wants to live without fighting then just die without a fight.

His foil, Alice (Gainsbourg), is all fuss and control. She clings to the illusion of safety-security, specific resorts, law, etc. Even though she is the one in control of the family and the business, she is horrified whenever she becomes aware of her lack of control and requires constant consoling, which are normal responses, but repelling when her children must act like her caretakers—parentification, which is abuse.

In contrast, Neil abandons the safety of a resort and home. He chooses to be immersed among people while also unable to really engage in small talk or niceties. He shows his love for the children by not being a burden, conveying his love but willing to have them hate him if it eases their loss. He shows that he is hurt when they are understandably unwilling to continue contact on his terms-without inquisition and in vacation mode, but he accepts that. There is something very Jesus like in the way that he accepts death and condemnation without struggle, but visible disappointment. It suggests that the life that he opted out of had no peace. Alice thanks him for coming, which indicates that his presence is not always a given.

If there is a real tragedy in “Sundown,” it is the missed communication. The family has a right to feel betrayed and angry that he lied to them, especially considering the circumstances, but a grown man has a right not to return home. Everyone immediately jumped to the money, and after he reassures them that he is not interested, Alice withdraws and relegates Neil’s contact through Richard, the intermediary, not directly. So presumably up to that point, he has taken a back seat but done everything that he was supposed to do, but it is not enough, and he gets cut off. I understand that when he asks Alice to dinner, it feels as if he is trivializing the situation, but damn, isn’t there some middle ground from being together forever to never hanging out again? The kids’ reaction makes sense because they think that he arranged to have Alice killed.

Random question: were Neil and Alice step or blood siblings? It sounded like the latter, but I read the newspaper article that Neil read, and it said step. To be fair, that article was filled with incorrect information. I want to know more, but do not think that it matters. Leaving it out makes it seem less melodramatic and more organic.